A History of Western Society: Printed Page 74

Living in the Past

Triremes and Their Crews

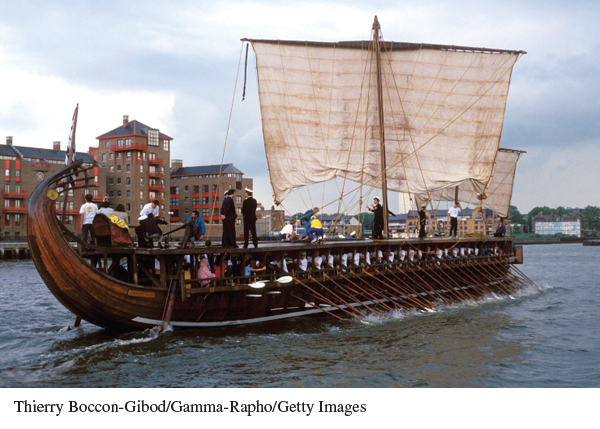

M en pulling long oars propelled Greek warships in battle. These ancient mariners were generally free men who earned good wages, although in times of intense warfare cities also used slaves because there were not enough free men available. An experienced rower was valuable because he had learned how to row in rhythm with many other men, and some rowers became professionals who hired themselves out to any military leader. By the sixth century B.C.E. the dominant form of warship in the Mediterranean was the trireme, with three rows of oars on each side and one man per oar. Triremes also had two sails for extra propulsion when the wind was favorable, and large steering oars at the back. The trireme usually carried 186 rowers, 14 soldiers for battles, a steersman who also served as navigator, and a captain.

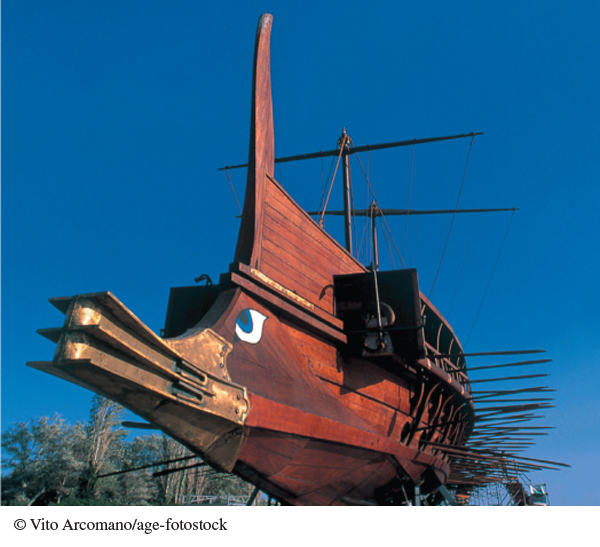

The hull, or frame, for the trireme was long and narrow like a stiletto blade, and the ship was built for speed, not comfort. A bronze battering ram capped the bow, or front of the ship. In battle the crews rowed as hard as possible to ram enemy ships. After smashing the enemy’s hull, the same rowers or soldiers who were on board the trireme swept over the side to capture the ship. Rowers often had to pull their oars hurriedly in reverse to free themselves from sinking enemy triremes.

Life aboard a trireme was cramped and uncomfortable. The crew sat about eight feet above the waves, and storms proved a constant danger. One captain described a particularly hard night at sea: “It was stormy, the place offered no harbor, and it was impossible to go ashore and get a meal. . . .

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

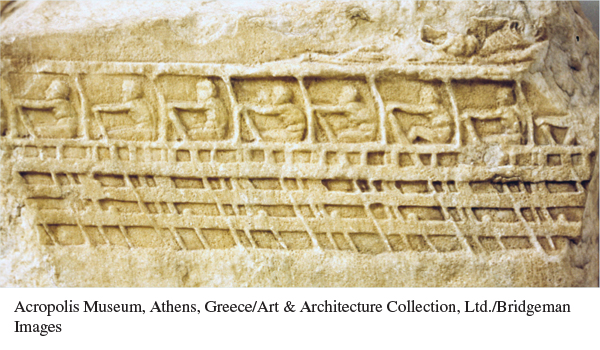

- In the relief from the Acropolis, how does the artist capture the physical effort of the oarsmen?

- Based on the relief and the photo of the modern reconstruction, why do you think rowing in time was so important?

- Triremes were well suited for war, but why would they not have worked well for trade?

Source: J. S. Morrison, Greek and Roman Oared Warships 399–30 B.C.E. (Oxbow Books, 1996).