A History of Western Society: Printed Page 82

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 84

Individuals in Society

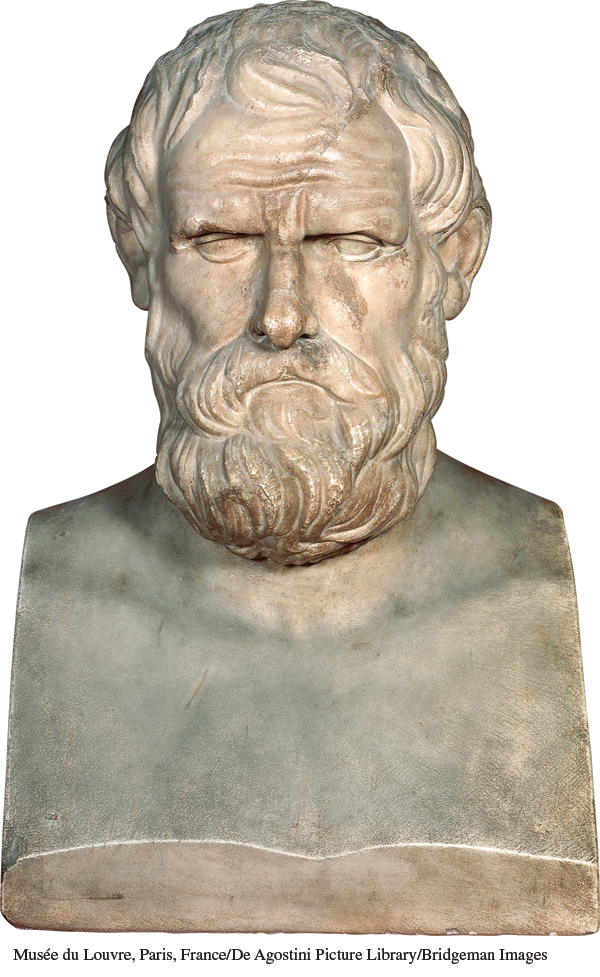

Aristophanes

I n 424 B.C.E., in the middle of the Peloponnesian War, citizens of Athens attending one of the city’s regular dramatic festivals watched The Knights, in which two slaves complain about their fellow slave’s power over their master Demos (“the people” in Greek) and everyone else around him. They run into a sausage seller and tell him that an oracle has predicted he will become more influential than their fellow slave and will eventually dominate the city, becoming what in ancient Greece was called a demagogue. He doesn’t think this possible, as he is only a sausage seller, but the men tell him he is the perfect candidate: “Mix and knead together all the state business as you do for your sausages. To win the people, always cook them some savoury that pleases them. Besides, you possess all the attributes of a demagogue; a screeching, horrible voice, a perverse, crossgrained nature and the language of the market-

Although the forceful slave’s name is never mentioned in the play, everyone knew he represented Cleon, at that point the leader of Athens, who had risen to power through populist speeches. The real Cleon may well have been among the thousands in the audience, as front-

That playwright was Aristophanes, the only comic playwright in classical Athens from whom whole plays survive. Not much is known about Aristophanes’s life, other than a few ambiguous clues in the plays. His first play, now lost, was produced in 427 B.C.E., and his last datable play, also now lost, in 386 B.C.E. (The dates of his life are inferred from these, as there is a comment in one play suggesting he was only eighteen when his first play was produced.) He directed some of his own plays, won the theater competition several times, and had sons who were also comic playwrights. Even in his early plays, Aristophanes seems to have opposed anything that was new in Athens: new types of leaders (like Cleon), new styles in drama (Euripides was a standard target), new kinds of educators (such as the Sophists), new philosophy (especially that of Socrates). Everything and everyone was open to ridicule, and the more obscene the better: poets throw turds at each other, politicians collapse drunk and vomiting in the streets, military leaders walk around with huge erections when their wives refuse to have sex with them until they call off the war. Aristophanes combined kinds of comedy that today are often separated — political satire, complicated wordplay, celebrity slamming, cross-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- How might political satires such as those of Aristophanes have both critiqued and reinforced civic values in classical Athens?

- Can you think of more recent parallels to Aristophanes’s political satires? What has been the response to these?