A History of Western Society: Printed Page 83

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 77

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 85

Gender and Sexuality

Citizenship was the basis of political power for men in ancient Athens and was inherited. After the middle of the fifth century B.C.E., people were considered citizens only if both parents were citizens, except for a few men given citizenship as a reward for service to the city. Adult male citizens were expected to take part in political decisions and be active in civic life, no matter what their occupation. (See “Thinking Like a Historian: Gender Roles in Classical Athens.”) They were also in charge of relations between the household and the wider community. Women in Athens and elsewhere in Greece, like those in Mesopotamia, brought dowries to their husbands upon marriage, which became the husband’s to invest or use, though he was supposed to do this wisely.

Women did not play a public role in classical Athens, and we know the names of no female poets, artists, or philosophers. Women in wealthier citizen families probably spent most of their time at home in the gynaeceum, leaving the house only to attend some religious festivals, and perhaps occasionally plays. The main function of women from citizen families was to bear and raise children. Childbirth could be dangerous for both mother and infant, so pregnant women usually made sacrifices or visited temples to ask help from the gods. Women relied on their relatives, on friends, and on midwives to assist in the delivery.

In the gynaeceum women oversaw domestic slaves and hired labor, and together with servants and friends worked wool into cloth. Women personally cared for slaves who became ill and nursed them back to health, and cared for the family’s material possessions as well. Women from noncitizen families lived freer lives than citizen women, although they worked harder and had fewer material comforts. They performed manual labor in the fields or sold goods or services in the agora, going about their affairs much as men did.

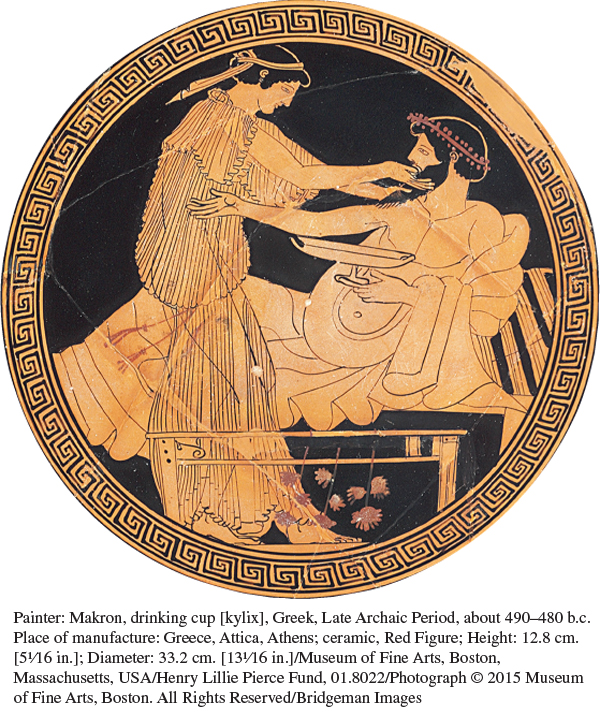

Among the services that some women and men sold was sex. Women who sold sexual services ranged from poor streetwalkers known as pornai to middle-

Same-

Along with praise of intellectualized love, Greek authors also celebrated physical sex and desire. The soldier-

He appears to me, that one, equal to the gods,

the man who, facing you,

is seated and, up close, that sweet voice of yours

he listens to

And how you laugh your charming laugh. Why it

makes my heart flutter within my breast,

because the moment I look at you, right then, for me,

to make any sound at all won’t work any more.

My tongue has a breakdown and a delicate

— all of a sudden — fire rushes under my skin.

With my eyes I see not a thing, and there is a roar

that my ears make.

Sweat pours down me and a trembling

seizes all of me; paler than grass

am I, and a little short of death

do I appear to me.7

Sappho’s description of the physical reactions caused by love — and jealousy — reaches across the centuries. The Hellenic, and even more the Hellenistic, Greeks regarded her as a great lyric poet, although because some of her poetry is directed toward women, over the last century she has become better known for her sexuality than her writing. Today the English word lesbian is derived from Sappho’s home island of Lesbos.

Same-