A History of Western Society: Printed Page 104

Living in the Past

Farming in the Hellenistic World

T he robust urbanism of the Hellenistic period depended on a thriving agricultural base. Consequently, farming remained an essential part of the economy. Most people in this period worked on small family farms that they owned or rented, or on larger farms owned by wealthy absentee landlords. The mainstay of Hellenistic agriculture remained the triad of grain, vine, and olive.

Farmers relied on a simple plow pulled by oxen to break the ground and prepare the soil for planting. Plowing also controlled weeds and preserved soil moisture. Farmers further broke up the land with mattocks, a tool similar to a pickax. At harvest time they reaped the grain with sickles. Barley was more common than wheat because it was hardier and could grow in poorer soil; it was generally eaten as a cooked grain. Wheat, on the other hand, was the preferred grain for making bread. Lentils and beans served as food for both people and animals, and as fertilizer for the soil. Olive trees grew even in poor earth, and fruit trees added welcome sweets to the family diet. Whenever possible, farmers grew grapevines, as wine was a common drink in the Hellenistic world, where it was generally drunk mixed with water because the wine was so rough.

Men tended to do the plowing, while women and children hoed and weeded. Plowing and seeding were usually done in the autumn. Winter rains encouraged growth, and farmers harvested their crops in early summer. After the harvest, grain was spread over a circular threshing floor, where donkeys harnessed to a pole crushed the kernels. Grapes were harvested in early fall and left sitting for two weeks before being crushed into wine.

At harvest time people offered some of their crops to the gods in thanks and set aside another — no doubt larger — portion for paying their rents and taxes. Another portion was saved as seed for the next year, but the largest portion was stored to be eaten over the next months. With what was left, farmers treated themselves to a festive meal, enjoyed along with music and dancing as a short break from work.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

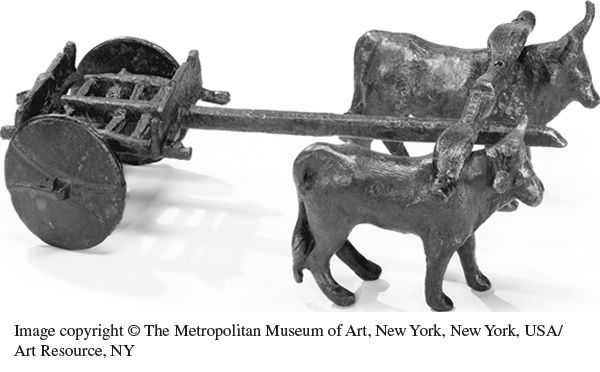

- Why would ox-

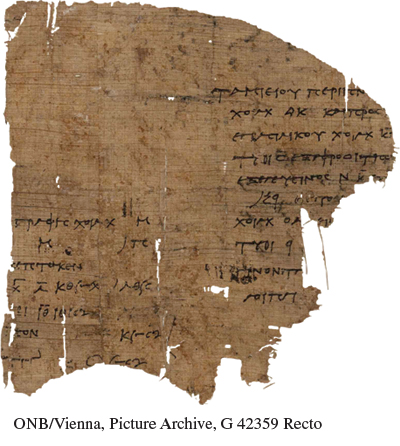

drawn carts and olive mills be common features of the rural economy in the Hellenistic world? - Given what you have read in this chapter, why do you think written records of agriculture, such as the papyrus manuscript shown at left, are rare historical sources for this period? Why would images of agricultural gods and goddesses, such as the figurine of Ceres shown above, be more common?