A History of Western Society: Printed Page 114

Thinking Like a Historian

Hellenistic Medicine

Hellenistic medical specialists based their ideas about the body and their handling of illness on observation, and also on the writings ascribed to the Greek physician Hippocrates and his followers. These were copied, recopied, edited, and expanded over the centuries, so it is impossible to say who wrote any specific work, but they contain ideas that were widely shared. How did Hellenistic physicians view the healthy body, and what did they recommend to maintain good health and treat sickness?

| 1 | Hippocratic Writings, The Nature of Man. This treatise discusses the structure of the human body and the causes of disease. |

![]() The human body contains blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. These are the things that make up its constitution and cause its pains and health. Health is primarily that state in which these constituent substances are in the correct proportion to each other, both in strength and quantity, and are well mixed. Pain occurs when one of the substances presents either a deficiency or an excess, or is separated in the body and not mixed with the others. . . .

The human body contains blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. These are the things that make up its constitution and cause its pains and health. Health is primarily that state in which these constituent substances are in the correct proportion to each other, both in strength and quantity, and are well mixed. Pain occurs when one of the substances presents either a deficiency or an excess, or is separated in the body and not mixed with the others. . . .

Now the quantity of the phlegm in the body increases in winter because it is that bodily substance most in keeping with the winter, seeing that it is the coldest. . . . The following signs show that winter fills the body with phlegm: people spit and blow from their noses the most phlegmatic mucus in winter; swellings become white especially at that season and other diseases show phlegmatic signs. . . .

And just as the year is governed at one time by winter, then by spring, then by summer, and then by autumn; so at one time in the body phlegm predominates, at another time blood, at another time yellow bile and this is followed by a preponderance of black bile. In these circumstances it follows that the diseases which increase in winter should decrease in summer and vice versa. . . .

Some diseases are produced by the manner of life that is followed; others by the life-

| 2 | Hippocratic Writings, Prognosis. This treatise provides guidance about how to examine a patient and determine if a disease will be fatal or not. |

![]() It seems to be highly desirable that a physician pay much attention to prognosis. If he is able to tell his patients when he visits them not only about their past and present symptoms, but also to tell them what is going to happen, as well as to fill in the details they have omitted, he will increase his reputation as a medical practitioner and people will have no qualms in putting themselves in his care. . . .

It seems to be highly desirable that a physician pay much attention to prognosis. If he is able to tell his patients when he visits them not only about their past and present symptoms, but also to tell them what is going to happen, as well as to fill in the details they have omitted, he will increase his reputation as a medical practitioner and people will have no qualms in putting themselves in his care. . . .

The signs to watch for in acute diseases are as follows: First, study the patient’s face; whether it has a healthy look and in particular whether it is exactly as it normally is. If the patient’s normal appearance is preserved, this is best; just as the more abnormal it is, the worse it is. . . .

Rapid breathing indicates either distress or inflammation of the organs above the diaphragm. Deep breaths taken at long intervals are a sign of delirium. If the expired air from the mouth and nostrils is cold, death is close at hand. . . .

The most helpful kinds of vomiting is that in which the matter consists of phlegm and bile, as well-

In all disease of the lungs, running at the nose and sneezing is bad.

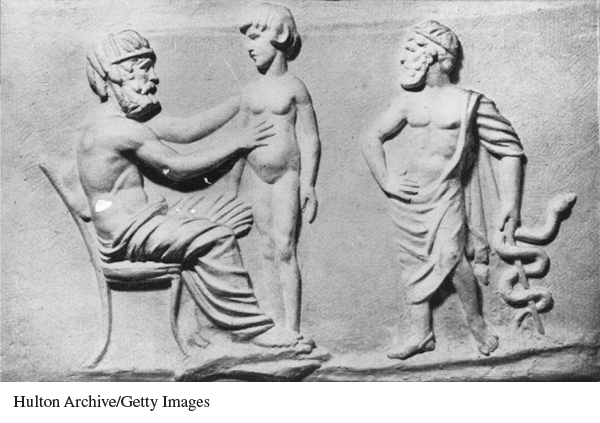

| 3 | Physician with young patient. This plaster cast from ca. 350 B.C.E. shows a physician examining a child, while Asclepius, the god of healing, observes. |

| 4 | Hippocratic Writings, Diseases. In this section of a long treatise, the author discusses treatment of people who have pus in the pleural cavity surrounding the lungs, which today is often linked with emphysema. |

![]() First cut the skin between the ribs with a knife with a rounded blade. Then take a sharp-

First cut the skin between the ribs with a knife with a rounded blade. Then take a sharp-

| 5 | Hippocratic Writings, A Regimen for Health. In this treatise the author provides suggestions for preventing illness. |

![]() People with a fleshy, soft, or ruddy appearance are best kept on a dry diet for the greater part of the year as they are constitutionally moist. Those with firm and tight-

People with a fleshy, soft, or ruddy appearance are best kept on a dry diet for the greater part of the year as they are constitutionally moist. Those with firm and tight-

Fat people who want to reduce should take their exercise on an empty stomach and sit down to their food out of breath. . . .

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- In Source 1, what are the basic substances in the body, and how do they create pain and illness? How is health shaped by the seasons and by people’s actions? By things in the air (which we would call germs, though the Greeks thought of them as poisons)?

- In Source 2, what does the author suggest that a physician pay attention to when diagnosing illness, and why is prognosis important? How does the technique of the physician in Source 3 fit with this advice?

- How does the author of Source 4 suggest infections in the pleural cavity be handled?

- What does the author of Source 5 recommend for people who want to stay healthy, and how does this advice differ for different types of individuals?

- Taking the sources together, what do these authors see as the most important role of physicians in preventing and treating illness? What do they see as the most important role of people themselves in maintaining their own health?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in the chapters in this book, write a short essay that analyzes ideas about health and illness in the Hellenistic world, and the treatments that resulted from these. What characterized a healthy body, and how was good health to be regained in the case of illness? Many of the ideas and treatments may seem strange, given how we understand the body today, but do any sound familiar?

Sources: (1) Hippocratic Writings, ed. G. E. R. Lloyd, trans. J. Chadwick and W. N. Mann (Harmondsworth, U.K.: Penguin, 1983), pp. 262, 264. Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd; (2) Hippocratic Writings, pp. 170–171, 172, 177; (4) James Longrigg, Greek Medicine: From the Heroic to the Hellenistic Age: A Source Book (London: Duckworth, 1998), 139; (5) Hippocratic Writings, p. 274.