A History of Western Society: Printed Page 133

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 129

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 135

Roman Families

The core of traditional Roman society was the family, although the word “family” (familia) in ancient Rome actually meant all those under the authority of a male head of household, including nonrelated slaves and servants. In poor families this group might be very small, but among the wealthy it could include hundreds of slaves and servants.

The male head of household was called the paterfamilias. Just as slave owners held power over their slaves, fathers held great power over their children, which technically lasted for their children’s whole lives. Initially this seems to have included power over life and death, but by the second century B.C.E. that had been limited by law and custom. Fathers continued to have the power to decide how family resources should be spent, however, and sons did not inherit until after their fathers had died.

In the early republic, legal authority over a woman generally passed from her father to her husband on marriage, but the Laws of the Twelve Tables allowed it to remain with her father even after a marriage. That was advantageous to the father, and could also be to the woman, for her father might be willing to take her side in a dispute with her husband, and she could return to her birth family if there was quarreling or abuse. By the late republic more and more marriages were of this type, and during the time of the empire (27 B.C.E.–476 C.E.) almost all of them were.

In order to marry, both spouses had to be free Roman citizens. Most citizens did marry, with women of wealthy families marrying in their midteens and non-

Weddings were central occasions in a family’s life, with spouses chosen carefully by parents, other family members, or marriage brokers. Professional fortune-

Women could inherit and own property under Roman law, though they generally received a smaller portion of any family inheritance than their brothers did. A woman’s inheritance usually came as her dowry on marriage. In the earliest Roman marriage laws, men could divorce their wives without any grounds while women could not divorce their husbands, but by the second century B.C.E. these laws had changed, and both men and women could initiate divorce. By then women had also gained greater control over their dowries and other family property, perhaps because Rome’s military conquests meant that many husbands were away for long periods of time and women needed some say over family finances. (See “Evaluating the Evidence 5.2: A Woman’s Actions in the Turia Inscription.”)

Although marriages were arranged by families primarily for the handing down of property to legitimate children, the Romans, somewhat contradictorily, viewed the model marriage as one in which husbands and wives were loyal to one another and shared interests and activities. The Romans praised women, like Lucretia of old, who were virtuous and loyal to their husbands and devoted to their children. Such praises emerge in literature, and also in epitaphs on tombstones, such as this one from around 130 B.C.E.:

Stranger, my message is short. Stand by and read it through. Here is the unlovely tomb of a lovely woman. Her parents called her Claudia by name. She loved her husband with all her heart. She bore two sons; of these she leaves one on earth; under the earth she has placed the other. She was charming in converse, yet gentle in bearing. She kept house, she made wool. That’s my last word. Go your way.6

Traditionally minded Romans thought that mothers should nurse their own children and personally see to their welfare. Non-

Most people in the expanding Roman Republic lived in the countryside. Farmers used oxen and donkeys to plow their fields, collecting the dung of the animals for fertilizer. Besides spreading manure, some farmers fertilized their fields by planting lupines and beans and plowing them under when they began to pod. Forage crops for animals to eat included clover, vetch, and alfalfa. Along with crops raised for local consumption and to pay their rents and taxes, many farmers raised crops to be sold. These included wheat, flax for making linen cloth, olives, and wine grapes.

Most Romans worked long days, and an influx of slaves from Rome’s wars and conquests provided additional labor for the fields, mines, and cities. To the Romans, slavery was a misfortune that befell some people, but it did not entail any racial theories. Slave boys and girls were occasionally formally apprenticed in trades such as leatherworking, weaving, or metalworking. Well-

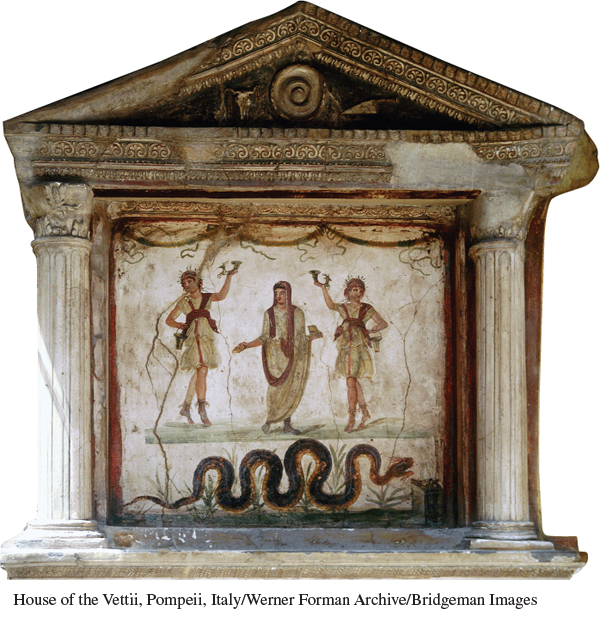

Membership in a family did not end with death, as the spirits of the family’s ancestors were understood to remain with the family. They and other gods regarded as protectors of the household — collectively these were called the lares and penates — were represented by small statues that stood in a special cupboard or a niche in the wall. The statues were taken out at meals and given small bits of food, or food was thrown into the household’s hearth for them. The lares and penates represented the gods at family celebrations such as weddings, and families took the statues with them when they moved. They were honored in special rituals and ceremonies, although the later Roman poet Ovid (43 B.C.E.–17 C.E.) commented that these did not have to be elaborate:

The spirits of the dead ask for little.

They are more grateful for piety than for an expensive gift —

Not greedy are the gods who haunt the Styx [the river that bordered the underworld] below.

A rooftile covered with a sacrificial crown,

Scattered kernels, a few grains of salt,

Bread dipped in wine, and loose violets —

These are enough.7