A History of Western Society: Printed Page 166

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 166

Chapter Chronology

Individuals in Society

Page 166

“M y uncle was stationed at Misenum, in active command of the fleet. On 24 August, in the early afternoon, my mother drew his attention to a cloud of unusual size and appearance. . . . My uncle’s scholarly acumen saw at once that it was important enough for a closer inspection, and he ordered a boat to be made ready.” So begins a letter from the statesman and writer Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus, describing what happened when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 C.E. Pliny provided terrifying details of clouds of hot ash, raining pumice stones, and sheets of fire, and then sang the praises of his uncle, also named Pliny, whose actions, “begun in a spirit of inquiry, [were] completed as a hero.” According to Pliny the Younger’s account, his uncle “steer[ed] his course straight for the danger zone with the intention of bringing help to many more people. . . . He was entirely fearless, describing each new movement and phase of the portent to be noted down exactly as he observed them . . . and when his helmsman advised him to turn back he refused, telling him that Fortune stood by the courageous.” The elder Pliny (23 C.E.–79 C.E.) died on the beach near Pompeii, most likely from inhaling fumes that aggravated his asthma. His body was discovered several days later when the smoke and ash cleared.

The younger Pliny used this letter to portray his uncle as a model of traditional Roman virtues, but some of what he related was not an exaggeration. Like many young men of his social class — the equestrian — Pliny the Elder studied law and then joined the army as an officer. He was involved in several military campaigns in Germany and also found time to write books, including a volume on military tactics and several biographies. He left military service during Nero’s reign and kept out of the limelight, writing noncontroversial books on grammar and rhetoric. After Nero committed suicide and Vespasian came to power, Pliny went back into government service, serving as the procurator (governor) of several different provinces. He again wrote biographies and histories, all of which are now lost, and the work that became his masterpiece, Natural History, an encyclopedia in which he sought to cover everything that was known to ancient Romans. In thirty-seven volumes, Natural History covers what we would now term biology, geology, astronomy, mineralogy, geography, ethnography, comparative anthropology, medicine, painting, building techniques, and many other subjects. Pliny’s “spirit of inquiry” shines through this work, which he researched through the study of hundreds of sources (all carefully cited) and wrote while he was traveling around in government service. It is one of the largest works to have survived from the Roman Empire and served as a source of knowledge into the Renaissance, when it was one of the very first classical books to be published after the invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century. Pliny finished a first draft in about 77 C.E. and was working on revisions when he was appointed fleet commander in the Roman navy and sent to Misenum, near Naples. There the cloud of smoke from the erupting Vesuvius was too interesting for him to ignore, and he set off in a boat to investigate, with deadly results.

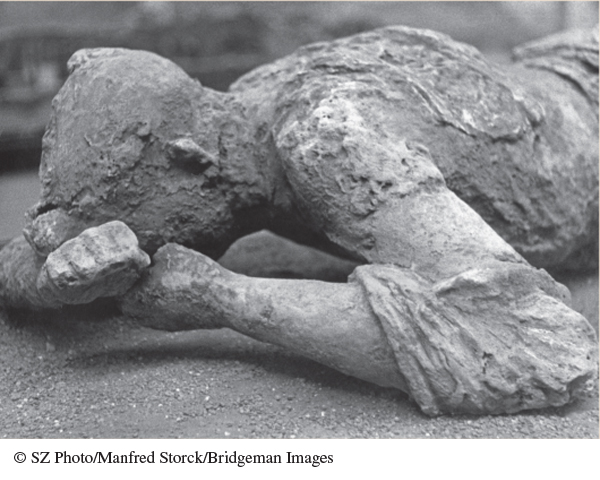

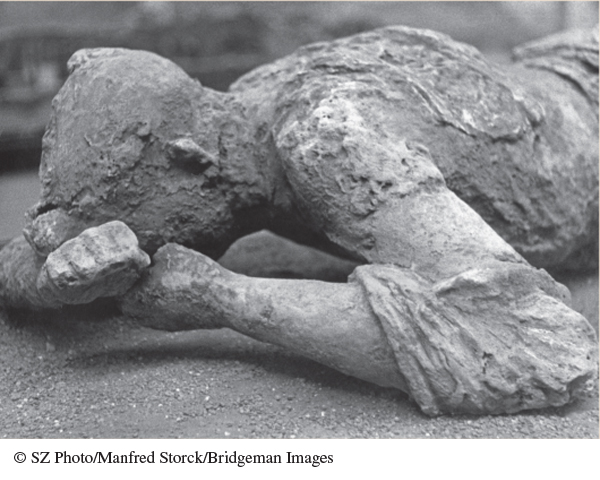

No contemporary portrait of Pliny the Elder survives, but his nephew reports that when his body was discovered, it was “still fully clothed and looking more like sleep than death.” When Pompeii was excavated, archaeologists used plaster to fill the voids in layers of ash that once held human bodies, allowing us to see the exact position a person was in when he or she died. This plaster cast is not Pliny but is as close to him in death as we can come.

(© SZ Photo/Manfred Storck/Bridgeman Images)

- What Roman ideals does the younger Pliny portray his uncle as exemplifying through his conduct during the eruption?

- How did army and government service in the Roman Empire provide opportunities for men of broad interests like Pliny?

Source: Quotations from Pliny the Younger, Letters 6.16, translated with an introduction by Betty Radice, vol. 1, pp. 166, 168 (Penguin Classics 1963, reprinted 1969). Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd.