A History of Western Society: Printed Page 156

Thinking Like a Historian

Army and Empire

Military might made it possible for the Romans to conquer and hold a huge empire. As the empire grew, the Romans needed to recruit troops from conquered areas and make these soldiers effective, loyal, and dependable. How did the Romans turn countless individuals from diverse cultures into the most powerful fighting force the Mediterranean world had ever seen?

| 1 | Julius Caesar, The Gallic War, 50 B.C.E. In his account of his successful campaigns in Gaul, designed to present himself as the consummate Roman military leader, Caesar (writing of himself in the third person) describes his efforts to rally his wavering troops. |

![]() Such a terrible panic suddenly seized our whole army as severely affected everyone’s courage and morale. Our men started asking questions, and the Gauls and traders replied by describing how tall and strong the Germans were, how unbelievably brave and skilful with weapons. . . .

Such a terrible panic suddenly seized our whole army as severely affected everyone’s courage and morale. Our men started asking questions, and the Gauls and traders replied by describing how tall and strong the Germans were, how unbelievably brave and skilful with weapons. . . .

| 2 | Titus Flavius Josephus, The Jewish War, ca. 75 C.E. Josephus was a commander in the Jewish revolt against the Romans in 66 C.E. who after he was taken prisoner went over to the Roman side. Here he describes how he used the Romans as a model for the Jewish army. Like Caesar in Source 1, he writes of himself in the third person. |

![]() Josephus knew that the invincible might of Rome was chiefly due to unhesitating obedience and to practice in arms. He despaired of providing similar instruction, demanding as it did a long period of training; but he saw that the habit of obedience resulted from the number of their officers, and he now reorganized his army on the Roman model, appointing more junior commanders than before. He divided the soldiers into different classes, and put them under decurions and centurions, those being subordinate to tribunes, and the tribunes to commanders of larger units. He taught them how to pass on signals, how to sound the advance and the retreat, how to make flank attacks and encircling movements, and how a victorious unit could relieve one in difficulties and assist any who were hard pressed. He explained all that contributed to toughness of body or fortitude of spirit. Above all he trained them for war by stressing Roman discipline at every turn: they would be facing men who by physical prowess and unshakable determination had conquered almost the entire world.

Josephus knew that the invincible might of Rome was chiefly due to unhesitating obedience and to practice in arms. He despaired of providing similar instruction, demanding as it did a long period of training; but he saw that the habit of obedience resulted from the number of their officers, and he now reorganized his army on the Roman model, appointing more junior commanders than before. He divided the soldiers into different classes, and put them under decurions and centurions, those being subordinate to tribunes, and the tribunes to commanders of larger units. He taught them how to pass on signals, how to sound the advance and the retreat, how to make flank attacks and encircling movements, and how a victorious unit could relieve one in difficulties and assist any who were hard pressed. He explained all that contributed to toughness of body or fortitude of spirit. Above all he trained them for war by stressing Roman discipline at every turn: they would be facing men who by physical prowess and unshakable determination had conquered almost the entire world.

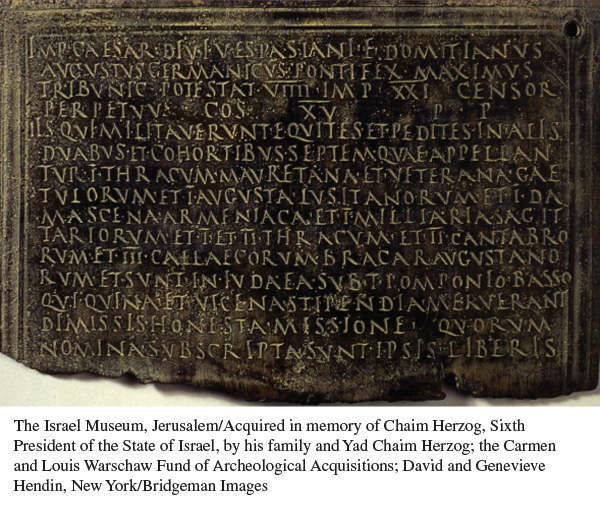

| 3 | Roman military diploma, 71 C.E. Military diplomas were bronze sheets, wired together, on which a former soldier’s tours of duty, record of service, and status as a citizen were recorded. One copy stayed in Rome, and one was sent to the soldier himself, much as members of the military today receive discharge papers. |

| 4 | Roman legion roof plaque. The legionaries of the Twentieth Legion (Leg. XX) stationed in Britain, whose symbol was a charging boar, made this clay plaque for the roof of one of their buildings. |

| 5 | Vegetius, Epitome of Military Science, ca. 380–390 C.E. Vegetius seems to have been a Roman imperial bureaucrat who set out what he saw as ideal military recruitment and training at a point when the Roman Empire was in decline and the army faced many challenges. |

![]() In every battle it is not numbers and untaught bravery so much as skill and training that generally produce the victory. For we see no other explanation of the conquest of the world by the Roman People than their drill-

In every battle it is not numbers and untaught bravery so much as skill and training that generally produce the victory. For we see no other explanation of the conquest of the world by the Roman People than their drill-

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- How does Julius Caesar use history and tradition in Source 1 to convince his troops to fight, and what do you think his purpose was in relating this incident as he did?

- What aspects of the Roman military does Josephus use as a model for his own forces in Source 2? How do these compare with the qualities Vegetius identifies in Source 5 as ideal in the perfect recruit?

- Why would the promise of eventual citizenship recorded in military diplomas, like the one in Source 3, have been an effective recruiting tool?

- What does the roof plaque in Source 4 suggest about the self-

identity of the soldiers who made it?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in Chapters 5 and 6, write a short essay that analyzes the military’s role in the empire’s expansion. How did the Romans turn countless individuals from diverse cultures into the most powerful fighting force the Mediterranean world had ever seen? How would you assess the relative importance of various factors in this transformation, and why might your assessment be different from that of the authors cited here?

Sources: (1) Julius Caesar, Seven Commentaries on the Gallic War, trans. Carolyn Hammond (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 24–27. By permission of Oxford University Press; (2) Josephus, The Jewish War, trans. G. A. Williamson (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1972), p. 172; (5) N. P. Milner, trans., Vegetius: Epitome of Military Science (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1996), pp. 2–8.