A History of Western Society AP®: Printed Page 648-c

CONCEPT 3.1

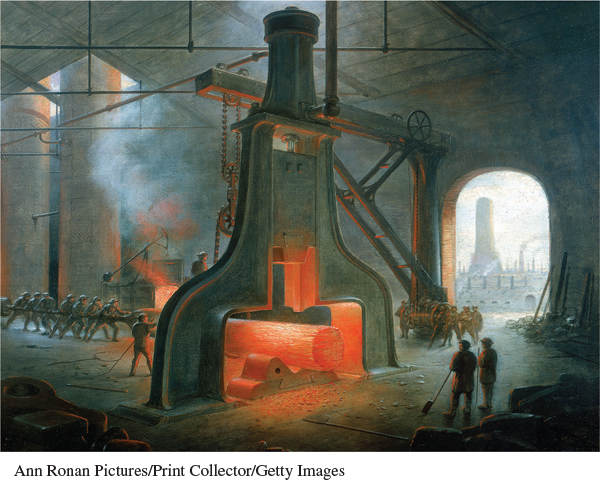

The Industrial Revolution

Industry developed first in Great Britain for a number of reasons. Britain benefited from rich natural resources, including coal and iron ore, which just happened to be close to rivers. Later canals, railroads, and steam power further improved the transportation infrastructure. Commercial expansion overseas brought in raw materials like cotton and created a global market for British goods. Wages were high compared to those in other parts of Europe, creating an incentive for manufacturers to develop machines to increase productivity, which happened first in cotton textiles. Relatively high wages meant ordinary English families could purchase manufactured goods and sometimes send their children to school, increasing literacy and helping create a broad culture of innovation. Although the British state did not invest directly in industry, it taxed its rapidly growing population aggressively, spending money on a navy to protect imperial commerce, and supported the development of new financial institutions that promoted commercial growth.

Some countries of continental Europe adopted British inventions in the nineteenth century and achieved their own patterns of innovation and economic expansion. In France, Belgium, and Prussia, governments bore the costs of building roads, canals, and railroads and put tariffs on imported goods to protect their new industries, working with new types of corporate banks, which also invested in railroads and factories. Under Prussian leadership, Germany was transformed into an industrial powerhouse and a unified country, particularly after 1860 in a “second industrial revolution” that centered on steel, chemicals, weapons, and transportation technology, manufactured in ever-