A History of Western Society AP®: Printed Page 648-e

The momentous economic and political transformations that began in the late eighteenth century engendered a broad array of responses. Conservatives believed authoritarian governments and hierarchical institutions were necessary to protect society from the baser elements of human nature, so they stressed tradition, a hereditary monarchy, a privileged landowning aristocracy, and an official state church. Powerful new ideologies — liberalism, nationalism, socialism, Marxism, anarchism, and others — emerged to oppose the revitalized conservatism. Liberals demanded equality before the law as well as individual freedoms such as freedom of the press and freedom of worship. They favored representative government, but generally wanted property qualifications that would limit the vote to a small number of the well-to-do, and wanted no government restrictions on private enterprise, a doctrine termed laissez faire. Radicals wanted to go further, advocating universal male suffrage and equal citizenship rights, while anarchists thought that all political power structures should be overthrown. Socialists incorporated problems created by industrialism into their thinking and wanted greater social equality, economic planning, and a fairer distribution of resources. Some had grand schemes for social improvement that proved unworkable, so they became known as “utopian” socialists.

Meanwhile, Karl Marx and other German socialist thinkers developed a political program based on the study of history that called for a working-class revolution to overthrow capitalist society. Marxists advocated unity among the working classes around the world, while nationalists thought that each people had its own special identity and destiny. Both Marxism and nationalism were ideas destined to have enormous influence in the twentieth as well as the nineteenth century. As nationalists sought to turn cultural unity into political reality, they often added a sense of national mission and ethnic superiority to their love of nation, two ideas that would lead to aggression and conflict. Some demagogic political leaders sought to build extreme nationalist movements by whipping up racial animosity toward imaginary enemies, especially Jews. The growth of vicious anti-Semitism spurred the emergence of Zionism, a Jewish political movement that advocated the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. Marxism gradually became more reformist than revolutionary, as workers formed labor unions and mass political parties that won tangible benefits in wages and working conditions, and pressured governments to adopt measures that would improve the quality of life for ordinary people, such as sewage systems and public transportation. Middle-class reform movements also worked for other types of political and social change, including rights for women and the end of slavery. (Pages 672–678, 682–697, 737–743, 778–788)

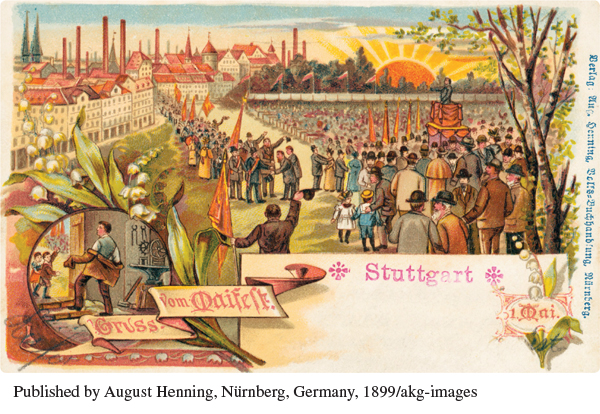

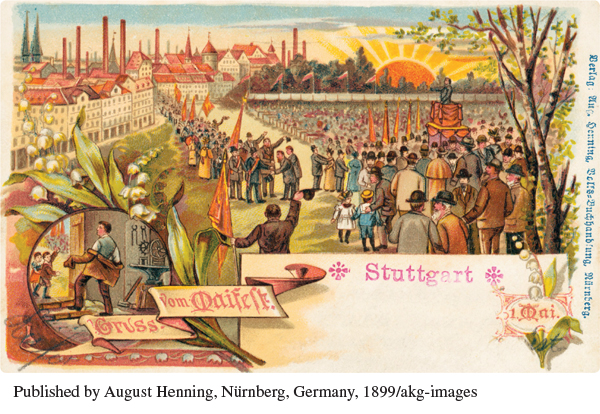

Published by August Henning, Nürnberg, Germany, 1899/akg-images