A History of Western Society AP®: Printed Page 826-d

CONCEPT 4.2

The Competing Ideologies and Policies of Communism, Fascism, and Capitalist Democracy

World War I proved to be an impetus for the development of ideologies that sought to revolutionize state and society, including communism and fascism, and also contributed to economic weaknesses that challenged capitalist democracies.

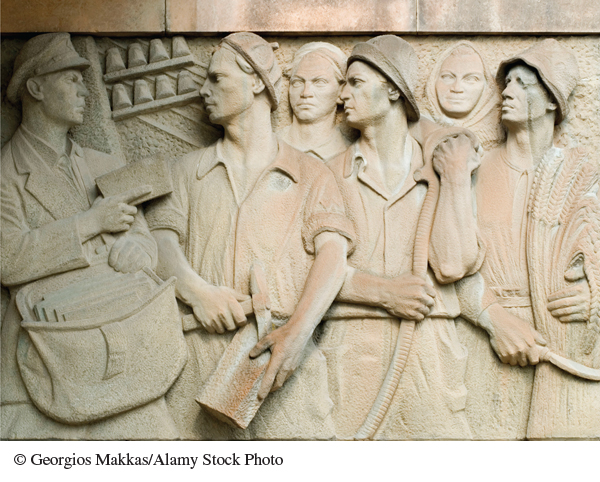

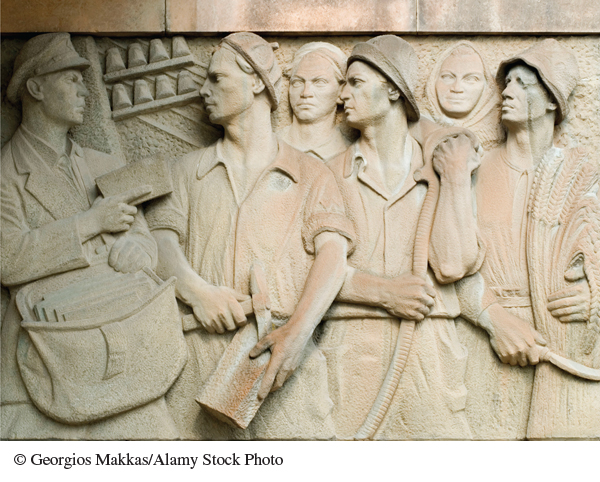

In Russia, huge losses and weak leadership combined with long-standing economic and political problems to lead first to a moderate socialist revolution, and then to a more radical turn under the leadership of Lenin. He updated Marx’s philosophy to address existing conditions in Russia, arguing that peasants as well as workers could remake society as long as they were led by a dedicated elite of revolutionaries. Lenin’s party, the Bolsheviks or Communists, seized power and held it through a long civil war by promising land reform, building a better army, and setting up a system of state control of the economy. Lenin re-established limited economic freedom in an attempt to rebuild agriculture and industry, but after his death his successor, Stalin, returned to centralized control. Stalin forcibly consolidated individual peasant farms into large collective enterprises, deporting to forced-labor camps any who resisted, which led to famine. He ordered the building of factories to produce steel and other industrial products, and millions of people moved to cities, where both men and women worked outside the home. While some people saw themselves as heroically building the world’s first socialist society, culture was thoroughly politicized for propaganda purposes. Alternative views were not tolerated, and this repression culminated in a series of trials and investigations that claimed millions of victims.

© Georgios Makkas/Alamy Stock Photo

Page 826-e

After World War II, eastern European nations remade state and society on the Soviet model, establishing one-party dictatorships, collectivizing agriculture and industry, and censoring culture. There were periodic attempts to liberalize the economy and open up society after Stalin’s death in 1953, and popular opposition to Soviet-style communism grew. In the mid-1980s, Gorbachev tried to revitalize the Soviet system with fundamental reforms designed to restructure the economy to meet the needs of ordinary people and allow greater openness in government and the media, but this policy snowballed out of control and anticommunist revolutions spread from eastern Europe to the Soviet Union itself, which broke apart.

Like communism under Stalin, fascism was a totalitarian form of government that made unprecedented total claims on the beliefs and behavior of citizens, used propaganda to build up the power of a charismatic leader, glorified violence, terrorized opponents, and engaged in massive projects of state-controlled social engineering.

In Italy and Germany, Mussolini and Hitler created states based on extreme nationalism and militarism, exploiting bitterness at the peace agreement after World War I and economic insecurity to take over dictatorial power, which was ended by military defeat. In western Europe, the massive economic downturn of the Great Depression led to a collapse in prices, a slowdown in production, bank failures, mass unemployment, increased poverty, and economic nationalism that disrupted trade and made problems worse. Governments in Scandinavia responded most successfully to the challenge, building on a pattern of cooperative social action to employ people in public works and increase social welfare benefits such as old-age pensions and subsidized housing, while in France extremist movements of the left and right sabotaged attempts at such measures.

After World War II, western and central Europe rebuilt with money from the United States and entered a period of unprecedented economic growth that saw a rising standard of living and remarkable growth in mass-produced consumer goods. They mixed government planning and free-market capitalism, and established generous welfare provisions, paid for by taxes, for all citizens. The postwar boom came to a close in the 1970s, opening a long period of economic stagnation, unemployment, and social dislocation. As a result, politics in western Europe drifted to the right, and leaders moved to cut government spending and support for social services like health care and education, privatize state industries, and promote free-market policies. (Pages 846–852, 891–898, 904–934, 952–963, 992–1014)