A History of Western Society AP®: Printed Page 826-e

CONCEPT 4.3

Intellectual Uncertainty, Moral Questioning, and Cultural Experimentation

Doubts about whether the world was rational and objectively knowable that had developed in the late nineteenth century were further enhanced by the senseless slaughter of World War I, which shattered beliefs in reason, progress, traditions, and God. Thinkers developed existentialism, a philosophy that stresses the meaninglessness of life as humans are born into it, and the need for people to create their own meaning and define themselves through their actions. Young people rejected even the body image of their parents, with ideals of slim youthfulness replacing those of the solid man (and woman) of substance. The new physics also challenged certainties, suggesting that the universe itself is relative and unstable, and that matter and energy are interchangeable, an idea that was fundamental to the development of the atomic bomb. Science and technology thus improved life, but also snuffed it out, and no longer provided optimistic answers about humanity’s place in an understandable world. The same was true of medicine, which extended the lifespan and made it better, but also developed techniques through which people could control and shape human life to a degree never before seen, provoking moral questions.

Religious thinkers and theologians responded to these challenges after World War I by revitalizing the fundamental beliefs of Christianity, suggesting that people should take a “leap of faith” and accept the existence of an unknowable but nonetheless awesome and majestic God. Christian leaders and ordinary believers varied in their responses to totalitarianism; some, including the pope, made agreements with fascist leaders or blended Christian and fascist ideas, while others resisted and were sometimes imprisoned or killed. In eastern Europe, especially in Poland, the Catholic Church thrived despite Communist attempts to suppress it, and helped create a realm of civil society beyond formal politics that would eventually bring down the Communist regime.

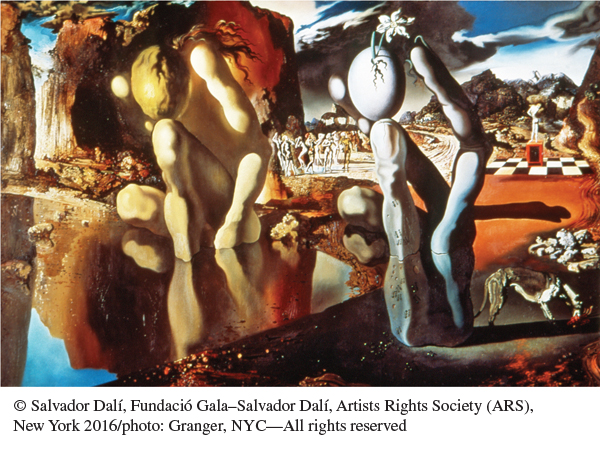

The trauma of World War I generated an outburst of cultural creation, as artists, writers, architects, and composers sought to portray the nightmarish quality of total war and called for radically new art forms that would express the modern condition, explore the human psyche in all its complexities, shock audiences, and point out the bankruptcy of traditional values. Many artists believed that art had a radical mission and could change the world. Thus when the Nazis came to power, hundreds of artists and intellectuals fled to the United States, and New York replaced Paris and Berlin as the global capital of high culture. In the first half of the twentieth century, the United States also became the primary source of modern popular culture, including mass-