A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 270

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 268

Chapter Chronology

Agriculture and Its Impact

Agriculture began very early in Africa. Knowledge of plant cultivation moved west from the Levant (modern Israel and Lebanon), arriving in the Nile Delta in Egypt about the fifth millennium B.C.E. Settled agriculture then traveled down the Nile Valley and moved west across the Sahel to the central and western Sudan. West Africans were living in agricultural communities by the first century B.C.E. From there plant cultivation spread to the equatorial forests. African farmers learned to domesticate plants, including millet, sorghum, and yams. Cereal-growing people probably taught forest people to plant grains on plots of land cleared by a method known as “slash and burn.” Gradually most Africans evolved a sedentary way of life: living in villages, clearing fields, relying on root crops, and fishing. Hunting-and-gathering societies survived only in scattered parts of Africa, particularly in the central rain forest region and in southern Africa.

Between 1500 B.C.E. and 1000 B.C.E. agriculture also spread southward from Ethiopia along the Great Rift Valley of present-day Kenya and Tanzania. Archaeological evidence reveals that the peoples of East Africa grew cereals, raised cattle, and used wooden and stone tools. Cattle raising spread more quickly than did planting, the herds prospering on the open savannas that are free of tsetse (SEHT-see) flies, which are devastating to cattle. Early East African peoples prized cattle highly. Many trading agreements, marriage alliances, political compacts, and treaties were negotiated in terms of cattle.

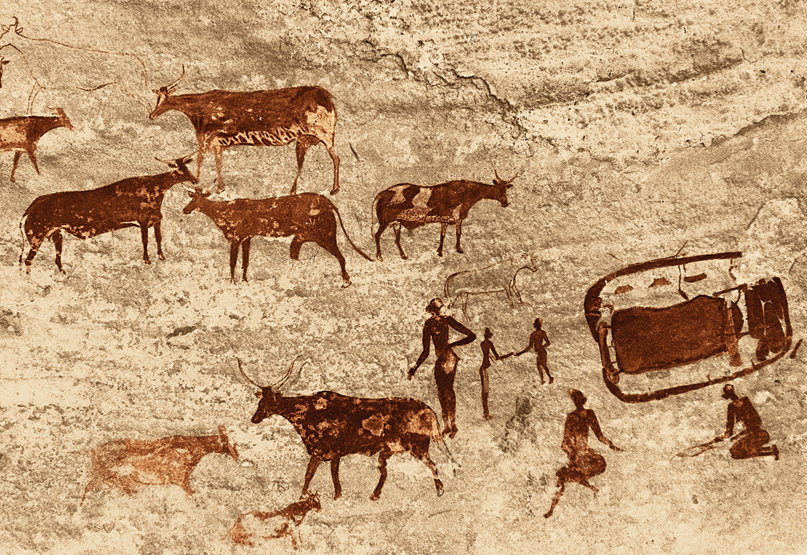

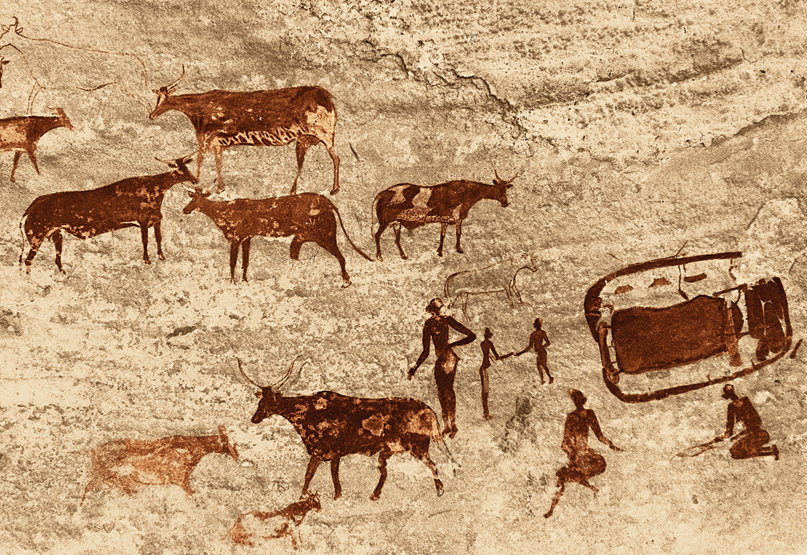

Rock Painting at Tassili, Algeria This scene of cattle grazing while a man stands guard over them was found on a rock face in Tassili n’Ajjer, a mountainous region in the Sahara where over fifteen thousand of these paintings have been catalogued. The oldest date back 9,000–12,000 years. Behind the man are perhaps his two children at play and his two wives working together in the compound. A cow stands in the enclosure to the right. (George Holton/Photo Researchers, Inc. Colorization by Robin Treadwell)

Cereals such as millet and sorghum are indigenous to Africa. Scholars speculate that traders brought bananas, taros (a type of yam), sugarcane, and coconut palms to Africa from Southeast Asia. Because tropical forest conditions were ideal for banana plants, their cultivation spread rapidly. Throughout sub-Saharan Africa native peoples also domesticated donkeys, pigs, chickens, geese, and ducks, although all these came from outside Africa. The guinea fowl appears to be the only animal native to Africa that was domesticated, despite the wide varieties of animal species in Africa. All the other large animals — elephants, hippopotamuses, giraffes, rhinoceros, and zebras — were simply too temperamental to domesticate.

The evolution from a hunter-gatherer life to a settled life had profound effects. In contrast to nomadic societies, settled societies made shared or common needs more apparent, and those needs strengthened ties among extended families. Agricultural and pastoral populations also increased, though scholars speculate that this increase did not remain steady, but rather fluctuated over time. Nor is it clear that population growth was accompanied by a commensurate increase in agricultural output.

Early African societies were similarly influenced by the spread of ironworking, though scholars dispute the route by which this technology spread to sub-Saharan Africa. Some believe the Phoenicians brought the iron-smelting technique to northwestern Africa, from which it spread southward. Others insist it spread westward from the Meroë (MEHR-oh-ee) region of the Nile. Most of West Africa had acquired ironworking by 250 B.C.E., however, and archaeologists believe Meroë achieved pre-eminence as an iron-smelting center only in the first century B.C.E. Thus a stronger case can probably be made for the Phoenicians. The great trans-Saharan trade routes (see “The Trans-Saharan Trade”) may have carried ironworking south from the Mediterranean coast. In any case, ancient iron tools found at the village of Nok on the Jos Plateau in present-day Nigeria seem to prove that ironworking industries existed in West Africa by at least 700 B.C.E. The Nok culture, which enjoys enduring fame for its fine terra-cotta sculptures, flourished from about 800 B.C.E. to 200 C.E.