A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 300

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 298

Settlement and Environment

Ancient settlers in the Americas adapted to and adapted diverse environments ranging from the high plateau of the Andes and central plateau of Mesoamerica to the tropical rain forest and river systems of the Amazon and Caribbean, as well as the prairies of North and South America. But, given the isolation of these societies, where did the first peoples to settle the continent come from?

The first settlers migrated from Asia, though their timing and their route are debated. One possibility is that the first settlers migrated across the Bering Strait from what is now Russia to Alaska and gradually migrated southward sometime between 15,000 and 13,000 B.C.E. But archaeological excavations have identified much earlier settlements along the Andes in South America, perhaps dating to over 40,000 years ago, than they have for Mesoamerica or North America. These findings suggest that the original settlers in the Americas arrived instead (or also) as fishermen circulating the Pacific Ocean.

Like early settlers elsewhere in the world, populations of the Americas could be divided into three categories: nomadic peoples, semi-

The earliest farming settlements emerged around 5000 B.C.E. These farming communities began the long process of domesticating and modifying plants, including maize (corn) and potatoes. Farmers also domesticated other crops native to the Americas such as peppers, beans, squash, and avocados.

The origins of maize in Mesoamerica are unclear, though it became a centerpiece of the Mesoamerican diet and spread across North and South America. Unlike other grains such as wheat and rice, the kernels of maize — which are the seeds as well as the part that is eaten for food — are wrapped in a husk, so the plant cannot propagate itself easily, meaning that farmers had to intervene to cultivate the crop. In addition, no direct ancestor of maize has been found. Biologists believe that Mesoamerican farmers identified a mutant form of a related grass called teosinte and gradually adapted it through selection and hybridization. Eaten together with beans, maize provided Mesoamerican peoples with a diet sufficient in protein despite the scarcity of meat. Mesoamericans processed kernels through nixtamalization, boiling the maize in a solution of water and mineral lime. The process broke down compounds in the kernels, increasing their nutritional value, while enriching the resulting masa, or paste, with dietary minerals including calcium, potassium, and iron.

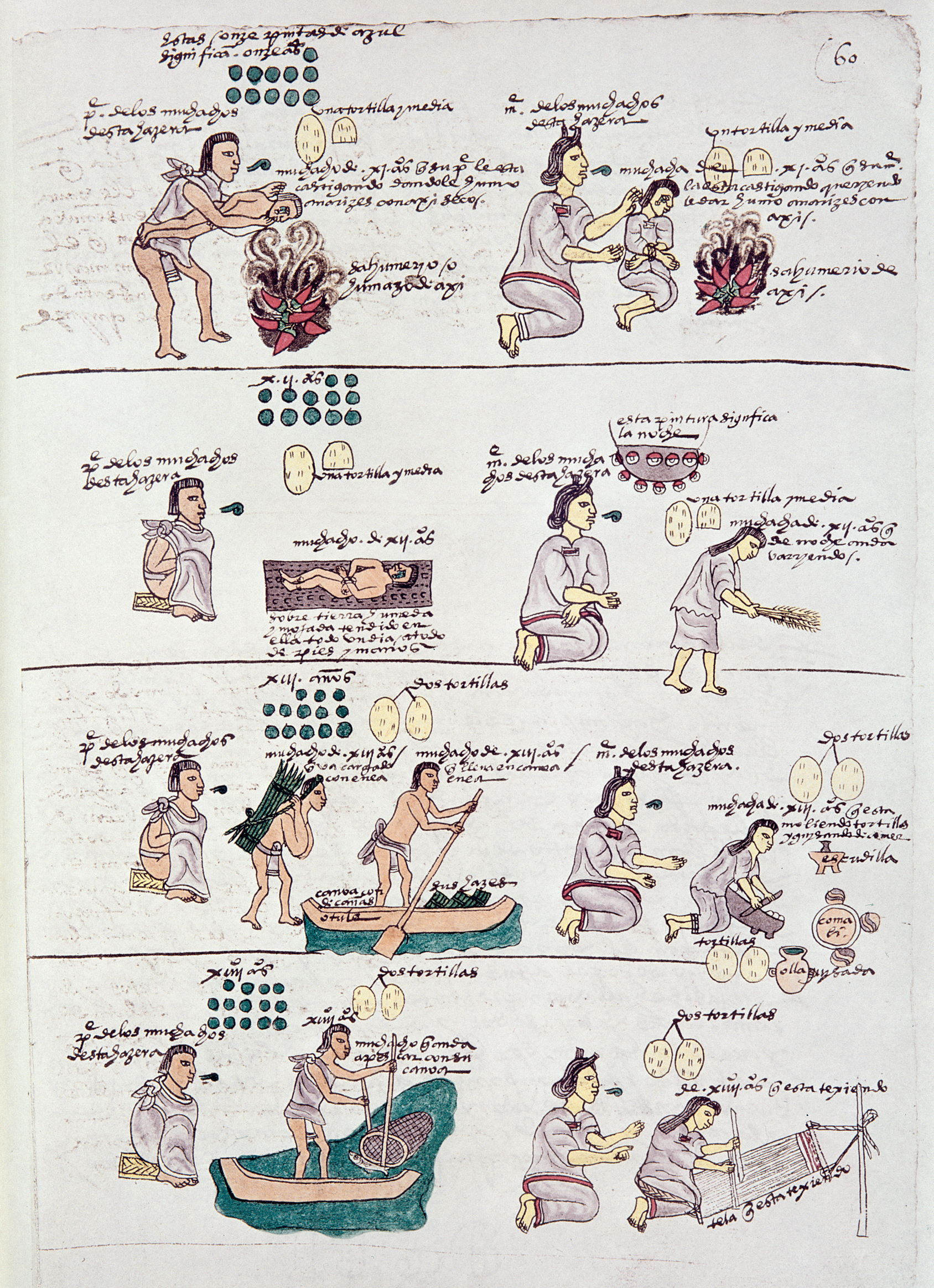

The masa could then be cooked with beans, meat, or other ingredients to make tamales. It could also be rolled flat on a stone called a metate and baked into tortillas. Tortillas played roles similar to bread in wheat-

Andean peoples cultivated another staple of the Americas, the potato. Potatoes first grew wild, but selective breeding produced many different varieties. For Andean peoples, potatoes became an integral part of a complex system of cultivation at varying altitudes. Communities created a system of “vertical archipelagos” through which they took advantage of the changes of climate along the steep escarpments of the Andes. Different crops could be cultivated at different altitudes, allowing communities to engage in intense and varied farming in what would otherwise have been inhospitable territory.

The settlement of communities, including what would become the largest cities, often took place at an altitude of nearly two miles (about 10,000 feet), in a temperate region at the boundary between ecological zones for growing maize and potatoes. The notable exception was the Lake Titicaca basin, at an elevation of 12,500 feet, where the abundance of fresh water tempered the climate and made irrigation possible. Communities raised multiple crops and engaged in year-

At higher elevations, members of these communities cultivated potatoes. Arid conditions across much of the altiplano, or high-

At middle altitudes, communities used terraces edged by stone walls to extend cultivation along steep mountainsides to grow corn. In the lowlands, they cultivated the high-