A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 402

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 400

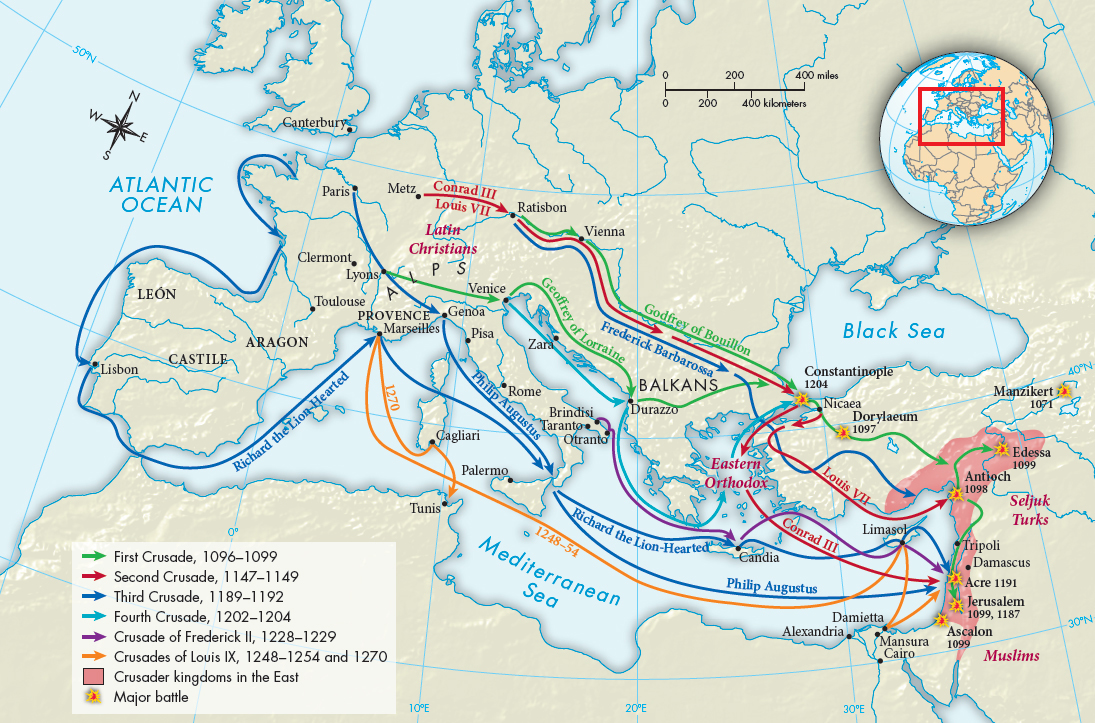

The Course of the Crusades

Thousands of people of all classes responded to Urban’s call, streaming southward and then toward Jerusalem in what became known as the First Crusade. The First Crusade was successful, mostly because of the dynamic enthusiasm of the participants, who had little more than religious zeal. They knew little of the geography or climate of the Middle East, and although there were several counts with military experience, the Crusaders could never agree on a leader. Adding to these disadvantages, supply lines were never set up, starvation and disease wracked the army, and the Turks slaughtered hundreds of noncombatants. Nevertheless, the army pressed on, besieging and taking several cities, including Antioch. (See “Viewpoints 14.1: Christian and Muslim Views of the Fall of Antioch.”) After a monthlong siege, the Crusaders took Jerusalem in July 1099 (Map 14.2). Fulcher of Chartres, a chaplain on the First Crusade, described the scene:

Amid the sound of trumpets and with everything in an uproar they attacked boldly, shouting “God help us!” . . . They ran with the greatest exultation as fast as they could into the city and joined their companions in pursuing and slaying their wicked enemies without cessation. . . . If you had been there your feet would have been stained to the ankles in the blood of the slain. What shall I say? None of them were left alive. Neither women nor children were spared.2

With Jerusalem taken, some Crusaders regarded their mission as accomplished and set off for home, but the appearance of more Muslim troops convinced other Crusaders that they needed to stay. Slowly institutions were set up to rule local territories and the Muslim population. Four small “Crusader states” — Jerusalem, Edessa, Tripoli, and Antioch — were established, and castles and fortified towns were built in these states to defend against Muslim reconquest. Reinforcements arrived in the form of pilgrims and fighters from Europe, so that there was constant coming and going by land and more often by sea after the Crusaders conquered port cities. Most Crusaders were men, but some women came along as well, assisting in the besieging of towns and castles by providing water to fighting men or foraging for food, working as washerwomen, and providing sexual services.

Between 1096 and 1270 the crusading ideal was expressed in eight papally approved expeditions, though none after the First Crusade accomplished very much. The Muslim states in the Middle East were politically fragmented when the Crusaders first came, and it took them about a century to reorganize. They did so dramatically under Saladin (Salah al-

After the Muslims retook Jerusalem, the crusading movement faced other setbacks. During the Fourth Crusade (1202–

In the late thirteenth century Turkish armies, after gradually conquering all other Muslim rulers, turned against the Crusader states. In 1291 the Christians’ last stronghold, the port of Acre, fell in a battle that was just as bloody as the first battle for Jerusalem two centuries earlier. Knights then needed a new battlefield for military actions, which some found in Spain, where the rulers of Aragon and Castile continued fighting Muslims until 1492.