A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 416

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 414

The Hundred Years’ War

While the plague ravaged populations in Asia, North Africa, and Europe, a long international war in western Europe added further death and destruction. England and France had engaged in sporadic military hostilities from the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066 (see “The Restoration of Order”), and in the middle of the fourteenth century these became more intense. From 1337 to 1453 the two countries intermittently fought one another in what was the longest war in European history, ultimately dubbed the Hundred Years’ War, though it actually lasted 116 years.

The Hundred Years’ War had a number of causes. Both England and France claimed the duchy of Aquitaine in southwestern France, and the English king Edward III argued that, as the grandson of an earlier French king, he should have rightfully inherited the French throne. Nobles in provinces on the borders of France who were worried about the growing power of the French king supported Edward, as did wealthy wool merchants and clothmakers in Flanders who depended on English wool. The governments of both England and France promised wealth and glory to those who fought, and each country portrayed the other as evil.

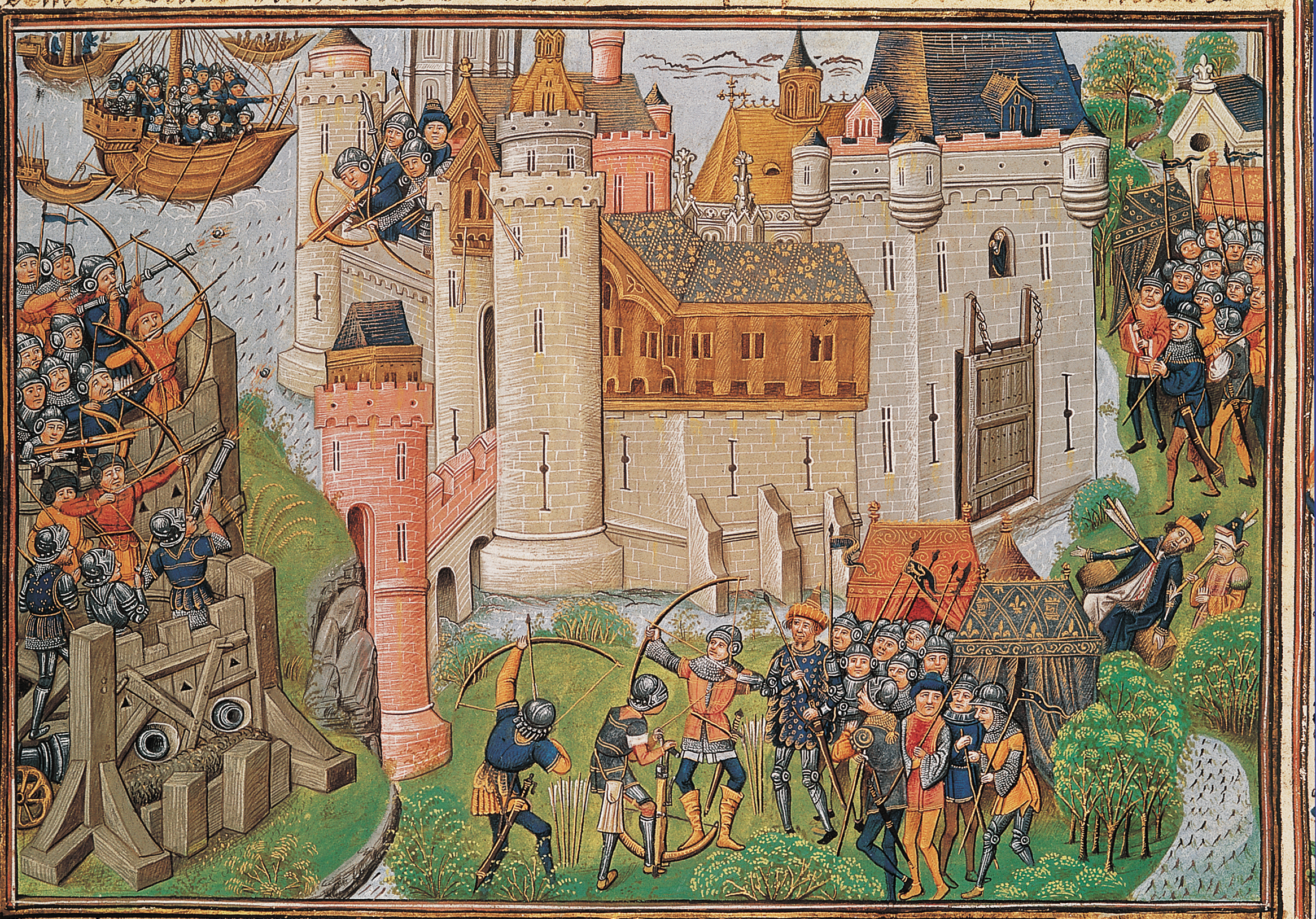

The war, fought almost entirely in France, consisted mainly of a series of random sieges and raids. During the war’s early stages, England was successful, primarily through the use of longbows fired by well-

The ultimate French success rests heavily on the actions of Joan, an obscure French peasant girl whose vision and military leadership revived French fortunes and led to victory. (Over the centuries, she acquired the name “of Arc” — d’Arc in French — based on her father’s name; she never used this name for herself, but called herself “the maiden” — la Pucelle in French.) Born in 1412 to well-

At Orléans, Joan inspired and led French attacks, and the English retreated. As a result of her successes, Charles made Joan co-

Joan and the French army continued their fight against the English. In 1430 England’s allies, the Burgundians, captured Joan and sold her to the English, and the French did not intervene. The English wanted Joan eliminated for obvious political reasons, but the primary charge against her was heresy, and the trial was conducted by church authorities. She was interrogated about the angelic voices and about why she wore men’s clothing. She apparently answered skillfully, but in 1431 the court condemned her as a heretic, and she was burned at the stake in the marketplace at Rouen. (A new trial in 1456 cleared her of all charges, and in 1920 she was canonized as a saint.) Joan continues to be a symbol of deep religious piety to some, of conservative nationalism to others, and of gender-

The long war had a profound impact on the two countries. In England and France the war promoted nationalism — the feeling of unity and identity that binds together a people. It led to technological experimentation, especially with gunpowder weaponry, whose firepower made the protective walls of stone castles obsolete. However, such weaponry also made warfare increasingly expensive. The war also stimulated the development of the English Parliament. Between 1250 and 1450 representative assemblies from several classes of society flourished in many European countries, but only the English Parliament became a powerful national body. Edward III’s constant need for money to pay for the war compelled him to summon it many times, and its representatives slowly built up their powers.