A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 482

Global Trade

Silver in vast quantities was discovered in 1545 by the Spanish, at an altitude of fifteen thousand feet, at Potosí in unsettled territory conquered from the Inca Empire. A half century later, 160,000 people lived in Potosí, making its population comparable to that of the city of London. In the second half of the sixteenth century the mine (in present-

Mining became the most important industry in the colonies. The Spanish crown claimed the quinto, one-

The real mover of world trade was not Europe, however, but China, which in this period had a population approaching 100 million. By 1450 the collapse of its paper currency had led the Ming government to shift to a silver-

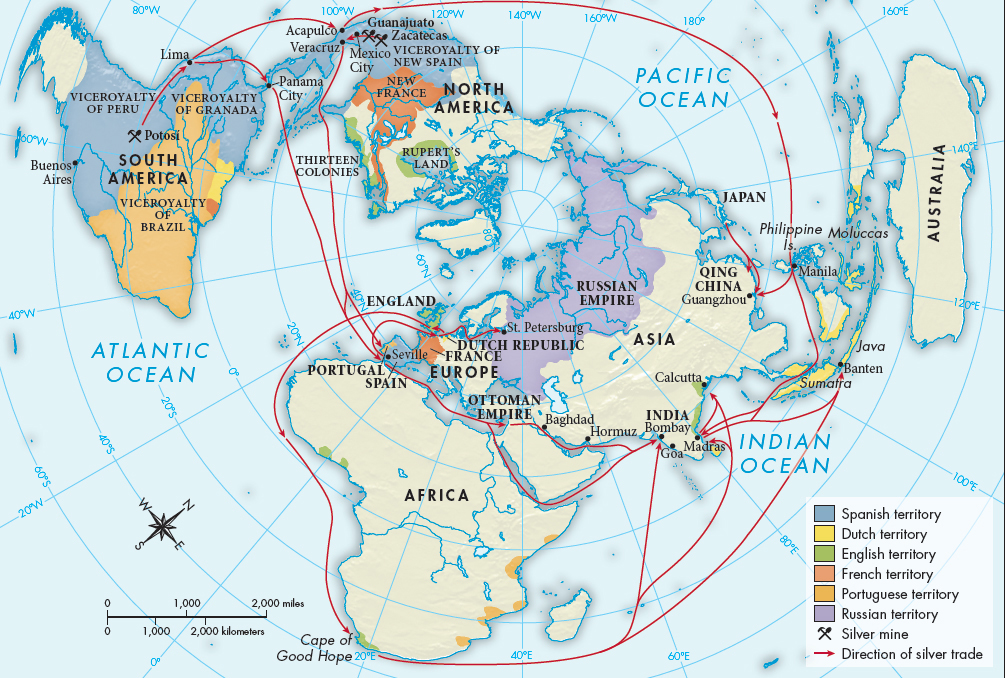

Japan was China's original source, and the Japanese continued to ship large quantities of silver ore until the depletion of its mines near the end of the seventeenth century. The discovery of silver in the New World provided a vast and welcome new supply for the Chinese market. In 1571 the Spanish founded a port city at Manila in the Philippines to serve as a bridge point for bringing silver to Asia. Throughout the seventeenth century Spanish galleons annually carried 2 million pesos (or more than fifty tons) of silver from Acapulco to Manila, where Chinese merchants carried it on to China. Even more silver reached China through exchange with European merchants who purchased Chinese goods using silver shipped across the Atlantic. European trade routes to China passed through the Baltic, the Mediterranean, and the Ottoman Empire, as well as around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa. Historians estimate that ultimately the majority of the world's silver in this period ended up in China.

In exchange for silver, the Chinese traded high-

Silver had a mixed impact on the regions involved. Spain's immense profits from silver paid for the tremendous expansion of its empire and for the large armies that defended it. However, the easy flow of money also dampened economic innovation. It exacerbated the rising inflation Spain was already experiencing in the mid-

China experienced similarly mixed effects. On the one hand, the need for finished goods to trade for silver led to the rise of a merchant class and a new specialization of regional production. On the other hand, inflation resulting from the influx of silver weakened the finances of the Ming Dynasty. As the purchasing power of silver declined in China, so did the value of silver taxes. The ensuing fiscal crisis helped bring down the Ming and led to the rise of the Qing in 1644. Ironically, the two states that benefited the most from silver — Ming China and Spain — also experienced political decline as a result of their reliance on it.

The consequences were most tragic elsewhere. In New Spain millions of indigenous laborers suffered brutal conditions and death in the silver mines. Demand for new labor for the mines contributed to the intensification of the African slave trade.

Silver ore mined at Potosí thus built the first global trade system in history. Previously, a long-

Silver remained a crucial element in world trade through the nineteenth century. When Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, it began to mint its own silver dollar, which became the most prized coin in trade in East Asia. By the beginning of the twentieth century, when the rest of the world had adopted gold as the standard of currency, only China and Mexico remained on the silver standard, testimony to the central role this metal had played in their histories.