A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 572

Listening to the Past

Denis Diderot’s “Supplement to Bougainville’s Voyage”

Listening to the Past

Denis Diderot’s “Supplement to Bougainville’s Voyage”

Denis Diderot was born in a provincial town in eastern France and educated in Paris. Rejecting careers in the church and the law, he devoted himself to literature and philosophy. In 1749, sixty years before Charles Darwin’s birth, Diderot was jailed by Parisian authorities for publishing an essay questioning God’s role in the creation and suggesting the autonomous evolution of species. Following these difficult beginnings, Diderot’s editorial work and writing on the Encyclopedia were the crowning intellectual achievements of his life and, according to some, of the Enlightenment itself.

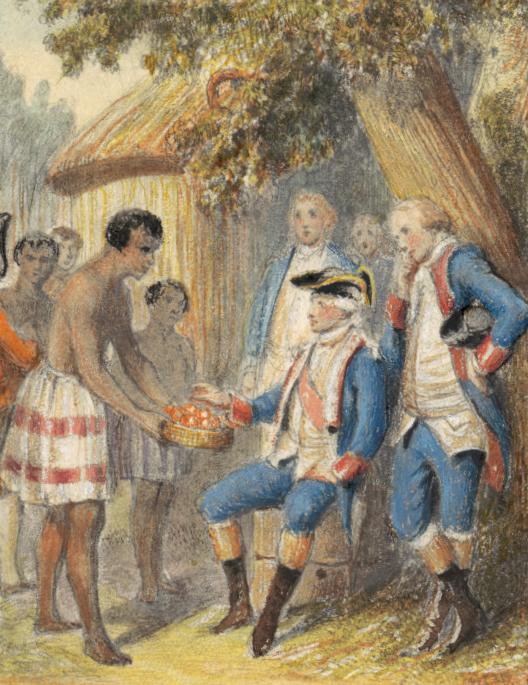

Like other philosophes, Diderot disseminated Enlightenment ideas through various types of writing, ranging from scholarly articles in the Encyclopedia to philosophical treatises, novels, plays, book reviews, and erotic stories. His “Supplement to Bougainville’s Voyage” (1772) was a fictional account of a European voyage to Tahiti inspired by the writings of traveler Louis-

“He was the father of a large family. When the Europeans arrived he looked upon them with scorn, showing neither astonishment, nor fear, nor curiosity. On their approach he turned his back and retired into his hut. Yet his silence and anxiety revealed his thoughts only too well; he was inwardly lamenting the eclipse of his countrymen’s happiness. When Bougainville was leaving the island, as the natives swarmed on the shore, clutching his clothes, clasping his companions in their arms and weeping, the old man made his way forward and proclaimed solemnly, “Weep, wretched natives of Tahiti, weep. But let it be for the coming and not the leaving of these ambitious, wicked men. One day you will know them better. One day they will come back, bearing in one hand the piece of wood you see in that man’s belt, and, in the other, the sword hanging by the side of that one, to enslave you, slaughter you, or make you captive to their follies and vices. One day you will be subject to them, as corrupt, vile and miserable as they are. . . .”

Then turning to Bougainville, he continued, “And you, leader of the ruffians who obey you, pull your ship away swiftly from these shores. We are innocent, we are content, and you can only spoil that happiness. We follow the pure instincts of nature, and you have tried to erase its impression from our hearts. Here, everything belongs to everyone, and you have preached I can’t tell what distinction between ‘yours’ and ‘mine.’ . . . If a Tahitian should one day land on your shores and engrave on one of your stones or on the bark of one of your trees, This land belongs to the people of Tahiti, what would you think then? You are stronger than we are, and what does that mean? When one of the miserable trinkets with which your ship is filled was taken away, what an uproar you made, what revenge you exacted! At that moment, in the depths of your heart, you were plotting the theft of an entire country! You are not a slave, you would rather die than be one, and yet you wish to make slaves of us. Do you suppose, then, that a Tahitian cannot defend his own liberty and die for it as well? This inhabitant of Tahiti, whom you wish to ensnare like an animal, is your brother. You are both children of Nature. What right do you have over him that he does not have over you? You came; did we attack you? Have we plundered your ship? Did we seize you and expose you to the arrows of our enemies? Did we harness you to work with our animals in the fields? We respected our own image in you.

“Leave us our ways; they are wiser and more decent than yours. We have no wish to exchange what you call our ignorance for your useless knowledge. Everything that we need and is good for us we already possess. Do we merit contempt because we have not learnt how to acquire superfluous needs? When we are hungry, we have enough to eat. When we are cold, we have enough to wear. You have entered our huts; what do you suppose we lack? Pursue as far as you wish what you call the comforts of life, but let sensible beings stop when they have no more to gain from their labours than imaginary benefits. If you persuade us to go beyond the strict bounds of necessity, when will we finish our work? When will we enjoy ourselves? We have kept our annual and daily labours within the smallest possible limits, because in our eyes nothing is better than rest. Go back to your own country to agitate and torment yourselves as much as you like. But leave us in peace. Do not fill our heads with your factitious needs and illusory virtues.”

Source: Edited excerpts from pages 41–

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- On what grounds does the speaker argue for the Tahitians’ basic equality with the Europeans?

- What is the good life, according to the speaker, and how does it contrast with the European way of life? Which do you think is the better path, and why?

- In what ways could Diderot’s thoughts here be seen as representative of Enlightenment ideas? Are there ways in which they are not?

- How realistic do you think this account is? Does it matter? How might defenders of colonial expansion respond to Diderot’s criticism?