A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 574

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 574

Enlightened Absolutism and Its Limits

Although Enlightenment thinkers were often critical of untrammeled despotism and eager for reform, their impact on politics was mixed. Outside of England and the Netherlands, especially in central and eastern Europe, most believed that political change could best come from above — from the ruler — rather than from below. Still, government officials’ daily involvement in complex affairs of state made them naturally attracted to ideas for improving human society. Encouraged and instructed by these officials, some absolutist rulers tried to reform their governments in accordance with Enlightenment ideals. The result was what historians have called the enlightened absolutism of the later eighteenth century. (Similar programs of reform in France and Spain will be discussed in Chapter 22.)

Influenced by the philosophes, Frederick II (r. 1740–

Frederick’s reputation as an enlightened prince was rivaled by that of Catherine the Great of Russia. When she was fifteen years old, Catherine’s family ties to the Romanov dynasty made her a suitable bride for the heir to the Russian throne. Catherine profited from her husband’s unpopularity and had him murdered so that she could be declared empress of Russia. Once in power, Catherine pursued three major goals. First, she worked hard to continue Peter the Great’s efforts to bring the culture of western Europe to Russia (see “Peter the Great and Russia’s Turn to the West” in Chapter 18). To do so, she patronized Western architects, sculptors, musicians, and Enlightenment philosophes and encouraged Russian nobles to follow her example. Catherine’s second goal was domestic reform. Like Frederick, she restricted the practice of torture, allowed limited religious tolerance, and tried to improve education and local government. The philosophes applauded these measures and hoped more would follow.

These hopes were dashed by a massive uprising of serfs in 1733 under the leadership of a Cossack soldier named Emelian Pugachev. Although Pugachev was ultimately captured and executed, his rebellion shocked Russian rulers and ended any reform programs Catherine might have intended to implement. After 1775 Catherine gave nobles absolute control of their serfs and extended serfdom into new areas. In 1785 she formally freed nobles from taxes and state service. Under Catherine the Russian nobility thus attained its most exalted position, and serfdom entered its most oppressive phase.

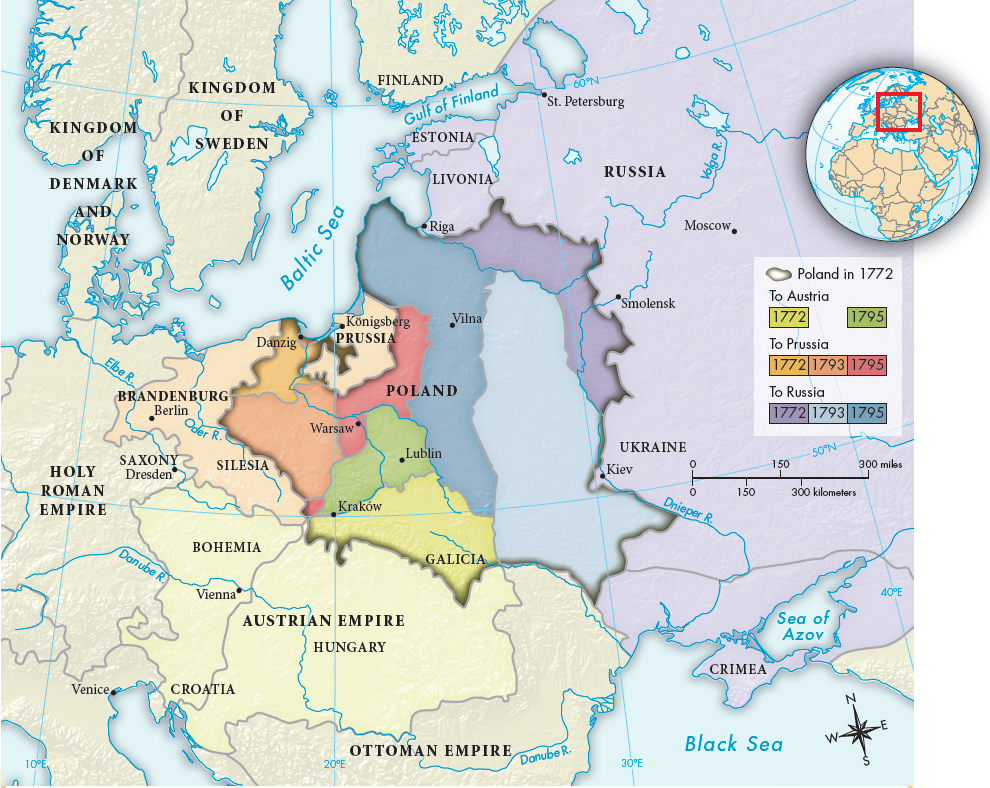

Catherine’s third goal was territorial expansion, and in this respect she was extremely successful. Her armies subjugated the last descendants of the Mongols and the Crimean Tartars and began the conquest of the Caucasus on the border between Europe and Asia. Her greatest coup was the partition of Poland, which took place in stages from 1772 to 1795 (Map 19.1).

Joseph II (r. 1780–

Perhaps the best examples of the limitations of enlightened absolutism are the debates surrounding the possible emancipation of the Jews. For the most part, Jews in Europe were confined to tiny, overcrowded ghettos; were excluded by law from most occupations; and could be ordered out of a kingdom at a moment’s notice. Still, a very few did manage to succeed and to obtain the right of permanent settlement, usually by performing some special service for the state, such as banking.

In the eighteenth century an Enlightenment movement known as the Haskalah emerged from within the European Jewish community, led by the Prussian philosopher Moses Mendelssohn (1729–

Arguments for tolerance won some ground, especially under Joseph II of Austria. Most monarchs, however, refused to entertain the idea of emancipation. In 1791 Catherine the Great established the Pale of Settlement, a territory encompassing modern-