A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 604

Global Trade

Slavesare people who are bound to servitude and often traded as property or as a commodity. The traffic in human persons bought and sold for the profits of their labor cannot decently be compared to the buying and selling of other commodities; people are not goods. But most societies, with the remarkable exception of the Aborigines in Australia, have treated people as goods and have engaged in the slave trade. Those who have been enslaved include captives in war, persons convicted of crimes, persons sold for debt, and persons bought and sold for sex. The ancient Greek philosophers, notably Aristotle, justified slavery as “natural.” The Middle Eastern monotheistic faiths — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — while professing the sacred dignity of each individual, and the Asian religious and sociopolitical ideologies of Buddhism and Confucianism, while stressing an ordered and harmonious society, all tolerated slavery and urged slaves’ obedience to established authorities. Until the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, most people everywhere accepted slavery as a “natural phenomenon.”

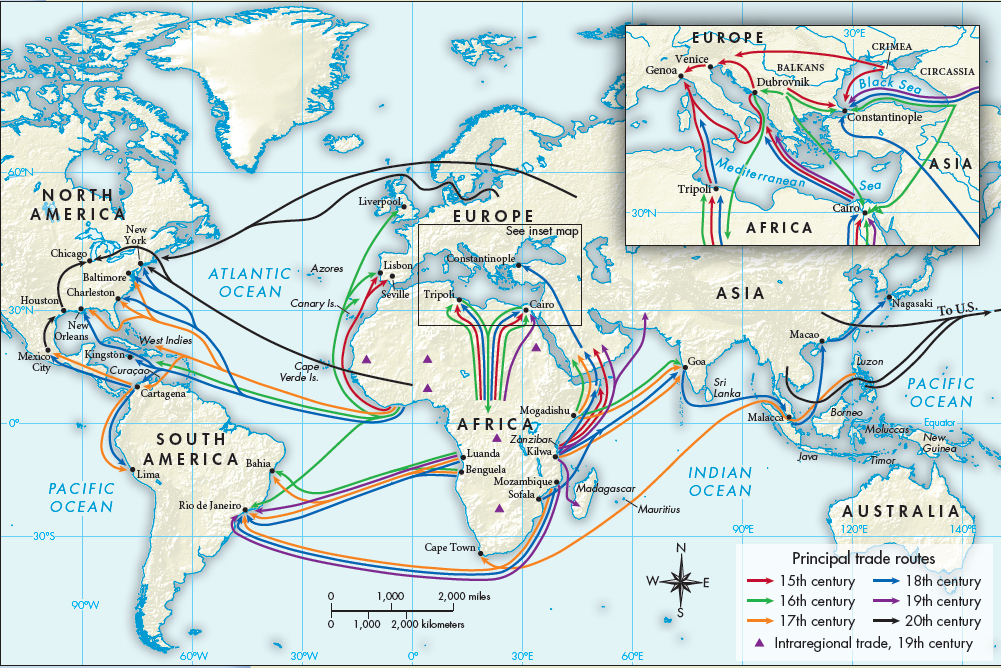

Between 1500 and 1900 the transatlantic African slave trade accounted for the largest number of people bought and sold. As such, and because of ample documentation, it has attracted much attention from scholars, and it also has led many people to identify the institution of slavery with African blacks. From a global perspective, however, the trade was far broader.

Slaves came from all over the world and included people of all races. The steady flow of white women and children from the Crimea, the Caucasus, and the Balkans in the fourteenth to eighteenth centuries for domestic, military, or sexual services in Ottoman lands, Italy, and sub-

The price of slaves varied widely over time and from market to market, according to age, sex, physical appearance, buyers’ perceptions of the social characteristics of each slave’s ethnic background, and changes in supply and demand. The Mediterranean and Indian Ocean markets preferred women for domestic service; the Atlantic markets wanted strong young men for mine and plantation work, for example. We have little solid information on prices for slaves in the Balkans, Caucasus, or Indian Ocean region. Even in the Atlantic trade, it is difficult to determine, over several centuries, the value of currencies, the cost and insurance on transported slaves, and the cost of goods exchanged for slaves. Yet the gold-

How is the human toll of slavery measured? Transformations within societies occurred not only because of local developments but also because of interactions among regions. For example, the virulent racism that in so many ways defines the American experience resulted partly from medieval European habits of dehumanizing the enemy (English versus Irish, German versus Slav, Christian versus Jew and Muslim) and partly from the movement of peoples and ideas all over the globe. American gold prospectors in the 1850s carried the bigotry they had heaped on blacks in the Americas to Australia, where it conditioned attitudes toward Asians and other peoples of color. Racism, like the slave trade, is a global phenomenon.

For all the cries for human rights today, the slave trade continues on a broad scale. The ancient Indian Ocean traffic in Indian girls and boys for “service” in the Persian Gulf oil kingdoms persists, as does the sale of African children for work in Asia. In 2011 an estimated 12 to 27 million people globally are held in one form of slavery or another. The U.S. State Department estimates that 15,000 to 18,000 enslaved foreign nationals are brought to the United States each year and, conservatively, perhaps as many as 50,000 people, mostly women and children, are in slavery in America at any given time. They have been bought, sold, tricked, and held in captivity, and their labor, often as sex slaves, has been exploited for the financial benefit of masters in a global enterprise.