A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 734

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 742

Chapter Chronology

Urban Development

Since the Middle Ages, European cities had been centers of government, culture, and large-scale commerce. They had also been congested, dirty, and unhealthy. Industrialization greatly worsened these conditions. The steam engine freed industrialists from dependence on the energy of fast-flowing streams and rivers so that by 1800 there was every incentive to build new factories in cities, which had better shipping facilities and a large and ready workforce. Therefore, as industry grew, overcrowded and unhealthy cities expanded rapidly.

In the 1820s and 1830s people in Britain and France began to worry about the condition of their cities. Except on the outskirts, each town or city was using every scrap of land to the full extent. Parks and open areas were almost nonexistent, and narrow houses were built wall to wall in long rows. Highly concentrated urban populations lived in extremely unsanitary conditions, with open drains and sewers flowing alongside or down the middle of unpaved streets. “Six, eight, and even ten occupying one room is anything but uncommon,” wrote a Scottish doctor for a government investigation in 1842.

The urban challenge — and the growth of socialist movements calling for radical change — eventually brought an energetic response from a generation of reformers. The most famous early reformer was Edwin Chadwick, a British official. Chadwick was a follower of radical British philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), whose approach to social issues, called utilitarianism, had taught that public problems ought to be dealt with on a rational, scientific basis and in a way that would yield the “greatest good for the greatest number.” Chadwick became convinced that disease and death actually caused poverty by increasing unemployment and depriving children of parents to provide for them. He also believed that cleaning up the urban environment would prevent disease.

Collecting detailed reports from local officials and publishing his findings in 1842, Chadwick concluded that the stinking excrement of communal outhouses could be carried off by water through sewers at less than one-twentieth the cost of removing it by hand. In 1848 Chadwick’s report became the basis of Great Britain’s first public health law, which created a national health board and gave cities broad authority to build modern sanitary systems. Such sanitary movements won dedicated supporters in the United States, France, and Germany from the 1840s on. By the 1860s and 1870s European cities were making real progress toward adequate water supplies and sewerage systems, and city dwellers were beginning to reap the reward of better health.

Early sanitary reformers were handicapped by the prevailing miasmatic theory of disease — the belief that people contract disease when they breathe foul odors. In the 1840s and 1850s keen observation by doctors and public health officials suggested that contagion spread through physical contact with filth and not by its odors, thus weakening the miasmatic idea. An understanding of how this occurred came out of the work of Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), who was named professor of chemistry in 1854 and subsequently developed the germ theory of disease. At the request of local brewers, Pasteur investigated fermentation and found that the growth of living organisms in a beverage could be suppressed by heating it — a process that became known as pasteurization. By 1870 the work of Pasteur and others had demonstrated that specific living organisms — germs (which we now divide into bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) — caused specific diseases and that those organisms could be controlled. These discoveries led to the development of a number of effective vaccines. Surgeons also applied the germ theory in hospitals, sterilizing not only the wound but everything else — hands, instruments, clothing — that entered the operating room.

The achievements of the bacterial revolution coupled with the public health movement saved millions of lives, particularly after about 1890. In England, France, and Germany death rates declined dramatically, and the awful death sentences of the past — diphtheria, typhoid, typhus, cholera, yellow fever — became vanishing diseases in the industrializing nations.

More effective urban planning after 1850 also improved the quality of urban life. France took the lead during the rule of Napoleon III (r. 1848–1870), who believed that rebuilding Paris would provide employment, improve living conditions, and glorify and strengthen his empire. In Baron Georges Haussmann (1809–1884), whom he placed in charge of Paris, Napoleon III found an authoritarian planner capable of bulldozing both buildings and opposition. In twenty years Paris was transformed. Haussmann destroyed the old medieval core of Paris to create broad tree-lined boulevards, long open vistas, monumental buildings, middle-class housing, parks, and improved sewers and aqueducts. The broad boulevards were designed in part to prevent a recurrence of the easy construction and defense of barricades by revolutionary crowds that had occurred in 1848. The new boulevards also facilitated traffic flow and provided impressive vistas. The rebuilding of Paris stimulated urban development throughout Europe, particularly after 1870.

Mass public transportation was also of great importance in the improvement of urban living conditions. In the 1870s many European cities authorized private companies to operate horse-drawn streetcars, which had been developed in the United States. Then in the 1890s countries in North America and Europe adopted another American transit innovation, the electric streetcar. Electric streetcars were cheaper, faster, more dependable, and more comfortable than their horse-drawn counterparts. Millions of riders hopped on board during the workweek. On weekends and holidays streetcars carried city people on outings to parks and the countryside, racetracks, and music halls.7 Electric streetcars also gave people of modest means access to improved housing, as the still-crowded city was able to expand and become less congested.

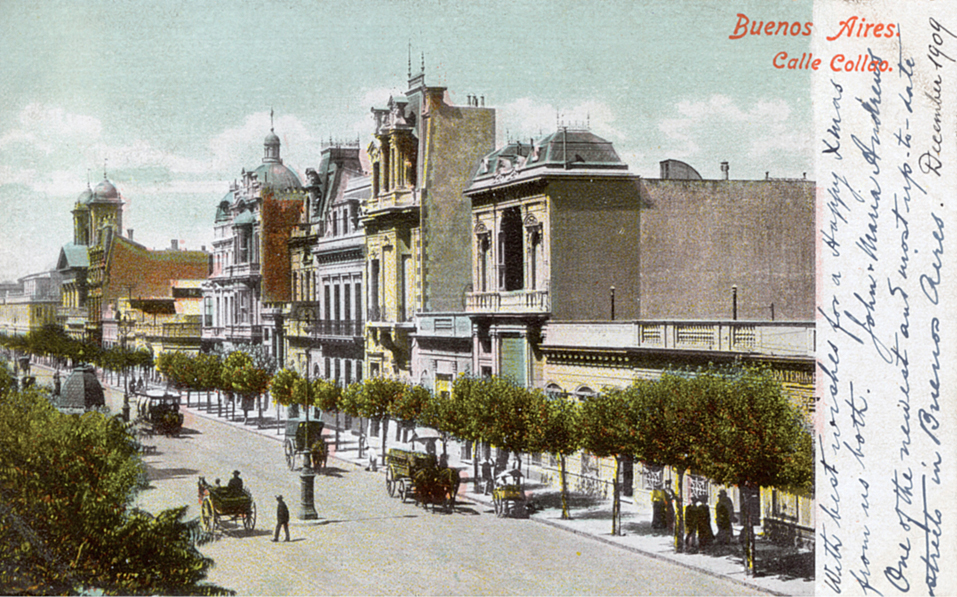

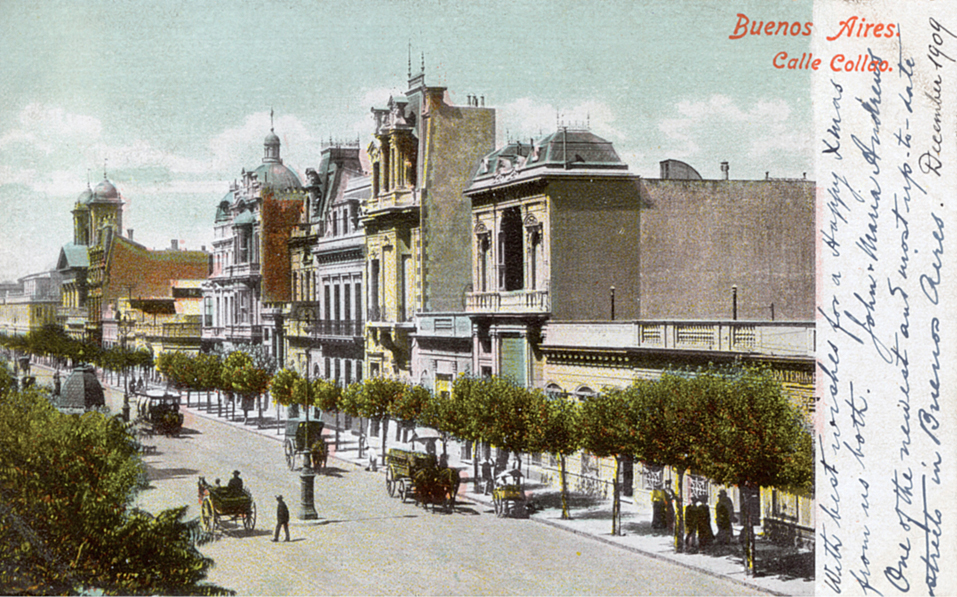

Buenos Aires Postcard, ca. 1908 Between 1880 and 1910 the modern city of Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina, emerged. City planners adopted the wide boulevards, monuments, and long vistas that Baron Haussmann had brought to Paris in the mid-nineteenth century. (© Mary Evans Picture Library/Grenville Collins Postcard Collection/The Image Works)

Industrialization and the growth of global trade also led to urbanization outside of Europe. The tremendous appetite of industrializing nations for raw materials, food, and other goods caused the rapid growth of port cities and mining centers across the world. These included Alexandria in Egypt, the major port for transporting Egyptian cotton, and mining cities like San Francisco in California and Johannesburg in South Africa. Many of these new cities consciously emulated European urban planning. For example, from 1880 to 1910 the Argentine capital of Buenos Aires modernized rapidly, introducing boulevards, an opera house, and many other amenities of the modernized city, leading it to be nicknamed the “Paris of South America.” The development of Buenos Aires was greatly stimulated by the arrival of many Italian and Spanish immigrants, part of a much larger wave of European migration in this period (see Chapter 27).