A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 753

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 763

Introduction for Chapter 25

25

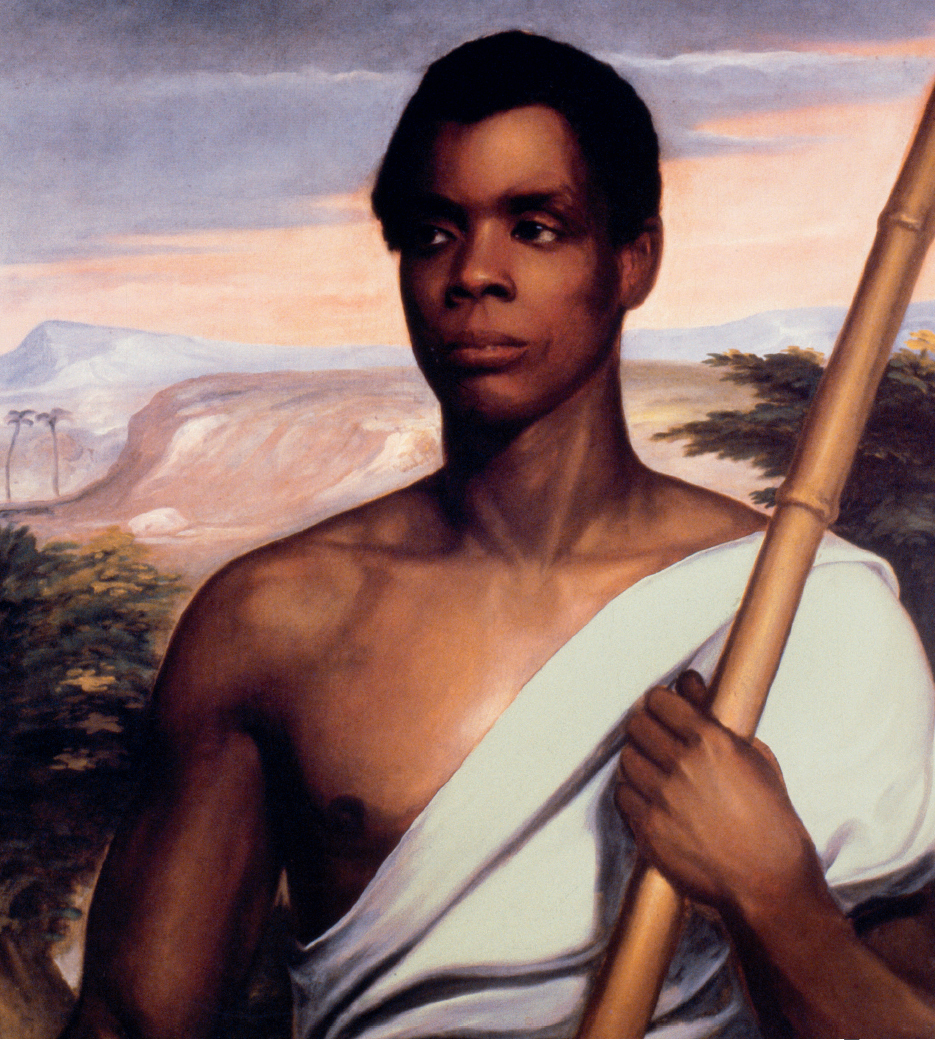

Africa, the Ottoman Empire, and the New Imperialism

1800–1914

While industrialization and nationalism were transforming society in Europe and the neo-

The political annexation of territory in the 1880s — the “new imperialism,” as it is often called by historians — was the capstone of Western society’s underlying economic and technological transformation. More directly, Western imperialism rested on a formidable combination of superior military might and strong authoritarian rule, and it posed a brutal challenge to African and Asian peoples. Indigenous societies met this Western challenge in different ways and with changing tactics. Nevertheless, by 1914 local elites in many lands were rallying their peoples and leading an anti-