A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 763

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 773

Colonialism’s Impact After 1900

By 1900 much of Africa had been conquered — or, as Europeans preferred to say, “pacified” — and a system of colonial administration was taking shape. In general, this system weakened or shattered the traditional social order and challenged accepted values.

The self-

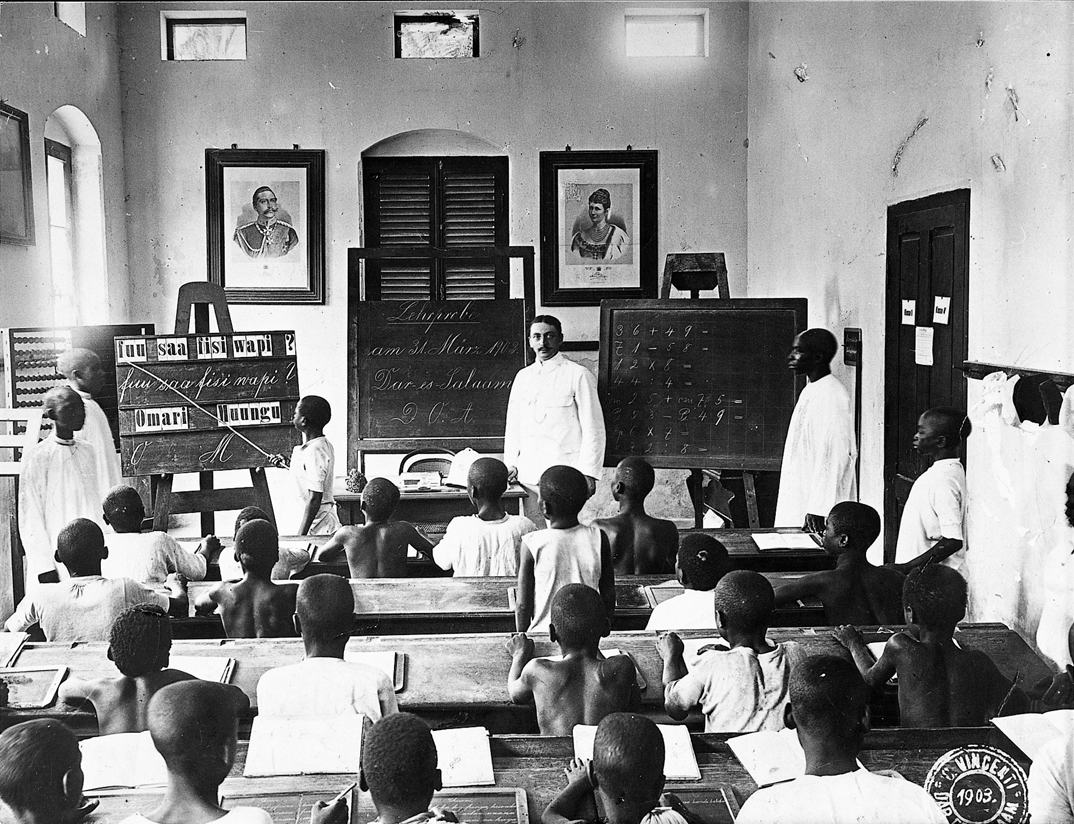

Colonial governments demonstrated much less interest in providing basic social services. Education, public health, hospital, and other social service expenditures increased after the Great War but still remained small. Europeans feared the political implications of mass education and typically relied instead on the modest efforts of state-

Economically, the colonial goal was to draw the African interior into the world economy on terms favorable to the dominant Europeans. The key was railroads linking coastal trading centers to outposts hundreds of miles in the interior. Cheap, dependable transportation facilitated easy shipment of raw materials out and manufactured goods in. Most African railroads, generally direct lines from sources of raw materials in the interior to coastal ports, were built after 1900; fifty-

The focus on economic development and low-

Colonial governments also often imposed head or hut taxes. Payable only in labor or European currency, these taxes compelled Africans to work for their white overlords. Africans despised no aspect of colonialism more than forced labor, widespread until about 1920. In some regions, particularly in West Africa, African peasants continued to respond freely to the new economic opportunities by voluntarily shifting to export crops on their own farms. Overall, the result of these developments was an increase in wage work and production geared to the world market and a decline in nomadic herding and traditional self-

In sum, the imposition of bureaucratic Western rule and the gradual growth of a world-

The British established the beginnings of the Gold Coast colony in 1821. Over the remainder of the century they extended their territorial rule inland from the coast and built up a fairly complex economy. This angered the powerful Asante kingdom in the interior, which had been expanding its rule toward the coast. After a series of Anglo-

Precolonial trade along the Gold Coast was vigorous and varied, with expanding exports of feathers, ivory, rubber, and palm oil. Into this sophisticated economy the British subsequently introduced cocoa bean production in 1878 for the world’s chocolate. Output rose spectacularly from a few hundred tons in the 1890s to 305,000 tons in 1936. Independent peasants and energetic African businessmen and businesswomen were mainly responsible for this enormous growth. Creative African entrepreneurs even built their own roads, and they sometimes reaped large profits. Gold production remained in African hands until the 1890s, when European companies began acquiring mines and extracting gold using modern techniques. Gold revenues went to the mining companies and the colonial government.

The Gold Coast also showed the way politically and culturally. The westernized black elite — relatively prosperous and well-

Across the continent in British East Africa (modern Kenya), events unfolded differently. In West Africa Europeans had been establishing trading posts since the 1400s and had carried on a complex slave trade for centuries. In East Africa there was very little European presence, other than some Portuguese, until after the scramble for Africa in the 1880s. Once the British started building their strategic railroad from the Indian Ocean across British East Africa in 1901, however, foreigners from Great Britain and India moved in to exploit the more welcoming environment. Indian settlers became shopkeepers, clerks, and laborers in the towns. British settlers dreamed of turning the cool, beautiful, and fertile East African highlands into a “white man’s country” like Southern Rhodesia or the Union of South Africa. They dismissed the local population of peasant farmers as barbarians, fit only to toil as cheap labor on their large estates and plantations. British East Africa’s blacks thus experienced much harsher colonial rule than did their fellow Africans in the Gold Coast, and they had to fight a long and violent war before gaining Kenyan independence in 1963.