A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 798

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 808

Chapter Chronology

The Self-Strengthening Movement

After the various rebellions were suppressed, forward-looking reformers began addressing the Western threat. Under the slogan “self-strengthening,” they set about modernizing the military along Western lines, establishing arsenals and dockyards. Recognizing that guns and ships were merely the surface manifestations of the Western powers’ economic strength, some of the most progressive reformers also initiated new industries, which in the 1870s and 1880s included railway lines, steam navigation companies, coal mines, telegraph lines, and cotton spinning and weaving factories. These were the same sorts of initiatives that the British were introducing in India, but China lagged behind, especially in railroads.

These measures drew resistance from conservatives, who thought copying Western practices was compounding defeat. A highly placed Manchu official objected that “from ancient down to modern times” there had never been “anyone who could use mathematics to raise a nation from a state of decline or to strengthen it in times of weakness.”3 Yet knowledge of the West gradually improved with more translations and travel in both directions. Newspapers covering world affairs began publication in Shanghai and Hong Kong. By 1880 China had embassies in London, Paris, Berlin, Madrid, Washington, Tokyo, and St. Petersburg.

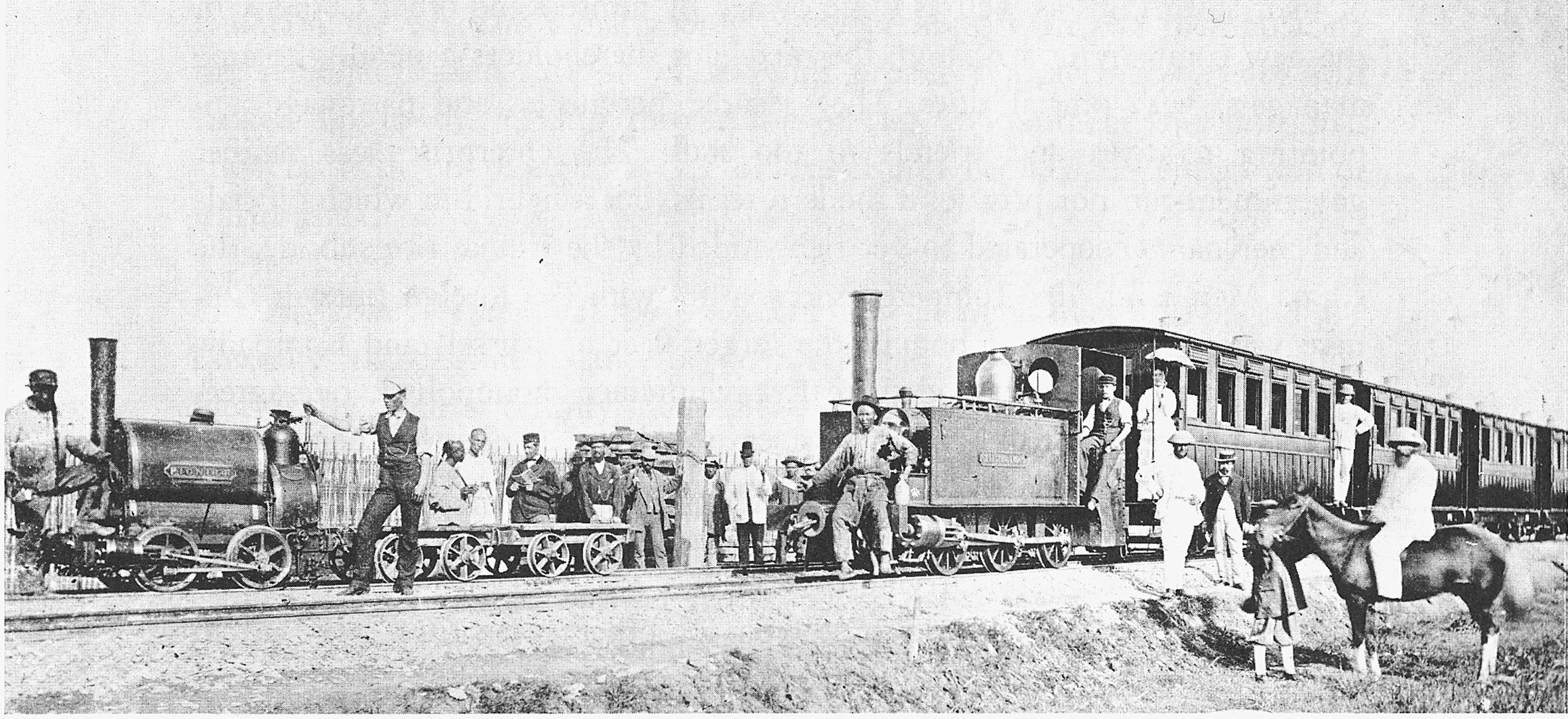

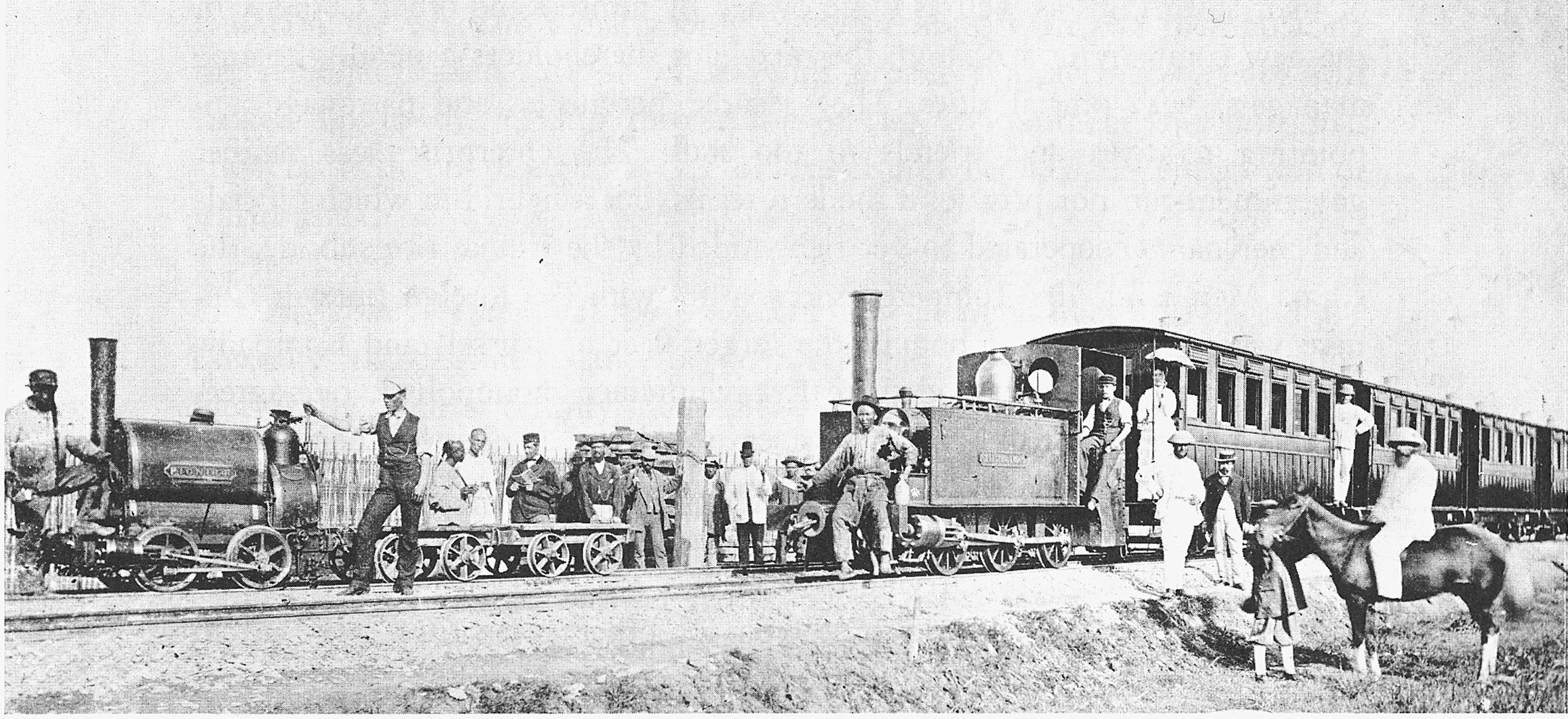

China’s First Railroad Soon after this 15-mile-long railroad was constructed near Shanghai in 1876 by the British firm of Jardine, Matheson, and Company, the provincial governor bought it in order to tear it out. Many Chinese of the period saw the introduction of railroads as harmful not only to the balance of nature but also to people’s livelihoods, since the railroads eliminated jobs in transport like dragging boats along canals or driving pack horses. (Private Collection/Visual Connection Archive)

Despite the enormous effort put into trying to catch up, China was humiliated yet again at the end of the nineteenth century. First came the discovery that Japan had so successfully modernized that it posed a threat to China. Then in 1894 Japanese efforts to separate Korea from Chinese influence led to the brief Sino-Japanese War in which China was decisively defeated even though much of its navy had been purchased abroad at great expense. In the peace negotiations, China ceded Taiwan to Japan, agreed to a huge indemnity (compensation for war expenses), and gave Japan the right to open factories in China. China’s helplessness in the face of aggression led to a scramble among the European powers for concessions and protectorates in China. At the high point of this rush in 1898, it appeared that the European powers might actually divide China among themselves, the way they had recently divided Africa.