A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 806

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 815

Settler Colonies in the Pacific: Australia and New Zealand

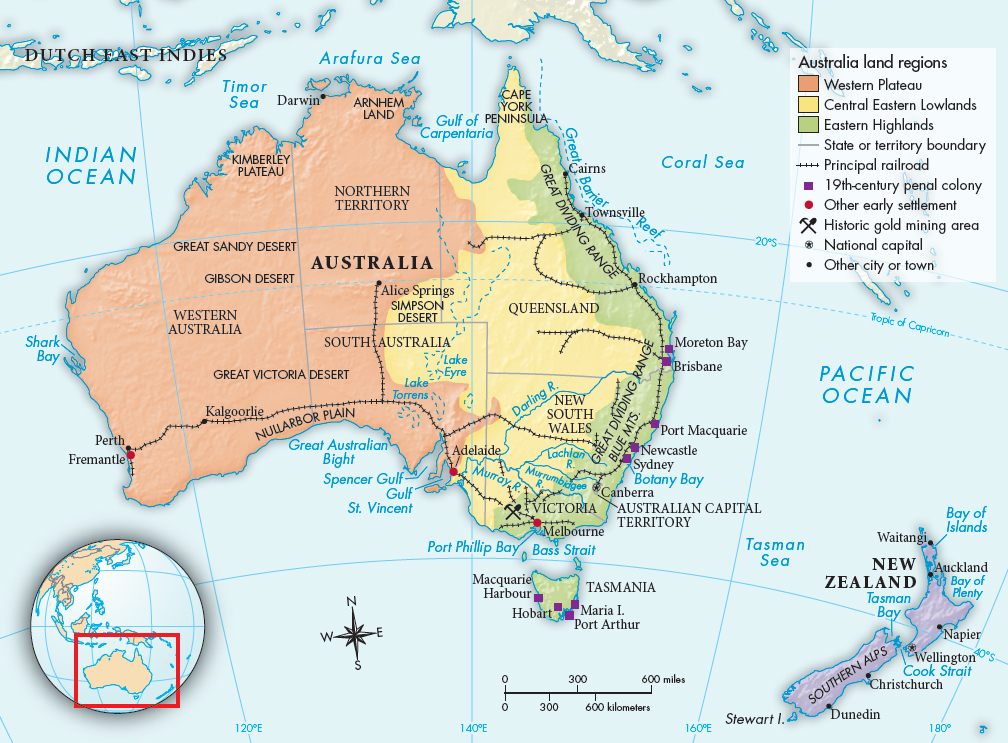

The largest share of the Europeans who moved to the Pacific region in the nineteenth century went to the settler colonies in Australia and New Zealand (Map 26.2). In 1770 the English explorer James Cook mapped the coast of New Zealand and then went on to Australia, which he declared suitable for settlement. Eight years later Cook was the first European to visit Hawaii. All three of these places in time became destinations for migrants.

Between 200 and 1300 C.E., Polynesians settled numerous islands of the Pacific, from New Zealand in the south to Hawaii in the north and Easter Island in the east. Thus most of the lands that explorers like Cook encountered were occupied by societies with chiefs, crop agriculture, domestic animals such as chickens and pigs, excellent sailing technology, and often considerable experience in warfare. Australia had been settled millennia earlier by a different population. When Cook arrived in Australia, it was occupied by about three hundred thousand Aborigines who lived entirely by food gathering, fishing, and hunting. Like the Indians of Central and South America, the people in all these lands fell victim to Eurasian diseases and died in large numbers. By 1900 there were only ninety thousand Aborigines in Australia.

Australia was first developed by Britain as a penal colony. In May 1787 a British fleet of eleven ships packed with one thousand felons and their jailers began an eight-

Governor Phillip and his successors urged the Colonial Office to send free settlers to Australia, not just prisoners. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, a steady stream of people relocated. Raising sheep proved suitable to Australia’s climate, and wool exports steadily increased, from 75,400 pounds in 1821, to 2 million pounds in 1830, to 24 million pounds in 1845. To encourage migration, the government offered free passage and free land to immigrants. By 1850 Australia had five hundred thousand inhabitants. The discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851 quadrupled that number in a few years. Although the government charged prospectors a very high license fee, men and women from all parts of the globe flocked to Australia to share in the fabulous wealth. The gold rush also provided the financial means for cultural development. Public libraries, museums, art galleries, and universities opened in the thirty years after 1851. These institutions dispensed a distinctly British culture, though a remote and provincial version.

Not everyone in Australia was of British origin, however. In Victoria in 1857 one adult male in seven was Chinese. “Colored peoples” (as all nonwhites were called in Australia) adapted more easily than the British to the warm climate and worked for lower wages. Thus they proved essential to the country’s economic development in the nineteenth century. Chinese and Japanese built the railroads and ran the shops in the towns and the market gardens nearby. Filipinos and Pacific Islanders did the hard work in the sugarcane fields. Afghans and their camels controlled the carrying trade in some areas. But fear that colored labor would lower living standards and undermine Australia’s distinctly British culture led to efforts to keep Australia white.

Australia gained independence in stages. In 1850 the British Parliament passed the Australian Colonies Government Act, which allowed the four most populous colonies — New South Wales, Tasmania, Victoria, and South Australia — to establish colonial legislatures, determine the franchise, and frame their own constitutions. In 1902 Australia became one of the first countries in the world to give women the vote. By then Australia had about 3.75 million people.

By 1900 New Zealand’s population had reached 750,000, only a fifth of Australia’s. One major reason more people had not settled these fertile islands was the resistance of the native Maori people. They quickly mastered the use of muskets and tried for decades to keep the British from taking their lands.

Foreign settlement in Hawaii began gradually. Initially, whalers stopped there for supplies, as they did at other Pacific Islands. The diseases they introduced took a heavy toll on the population, measles alone killing a fifth of the population in the 1850s. Missionaries and businessmen came next, and soon other settlers followed, both whites and Asians. A plantation economy developed centered on sugarcane. In the 1890s leading settler families overthrew the native monarchy, set up a republic, and urged the United States to annex Hawaii, which it did in 1898.