A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 835

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 846

Immigration to Latin America

In 1852 the Argentine political philosopher Juan Bautista Alberdi published Bases and Points of Departure for Argentine Political Organization, in which he argued that the development of his country depended on immigration. Indians and blacks, Alberdi maintained, lacked basic skills, and it would take too long to train them. Thus he pressed for massive immigration from northern Europe and the United States:

Each European who comes to our shores brings more civilization in his habits, which will later be passed on to our inhabitants, than many books of philosophy. . . . Do we want to sow and cultivate in America English liberty, French culture, and the diligence of men from Europe and from the United States? Let us bring living pieces of these qualities.5

Alberdi’s ideas, guided by the aphorism “to govern is to populate,” won immediate acceptance and were even incorporated into the Argentine constitution, which declared, “The Federal government will encourage European immigration.” Other Latin American countries adopted similar policies promoting immigration to achieve similar goals.

Coffee barons in Brazil, latifundiarios (owners of vast estates) in Argentina, or investors in nitrate and copper mining in Chile made enormous profits that they reinvested in new factories. Latin America had been tied to the Industrial Revolution in Britain and northern Europe from the outset as a provider of raw materials and as a consumer of industrial goods. In the major exporting countries of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, domestic industrialization now began to take hold in the form of textile mills, food-

By the turn of the twentieth century, industrial parks had emerged in Mexico City, Veracruz, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. In 1907 Brazil had an industrial working class of 150,000. By 1914 Argentina’s numbered 400,000. In Brazil and Argentina these workers were mainly European immigrants. The workers proved unexpectedly contentious: they brought with them radical ideologies that challenged liberalism, particularly anarchism and anarcho-

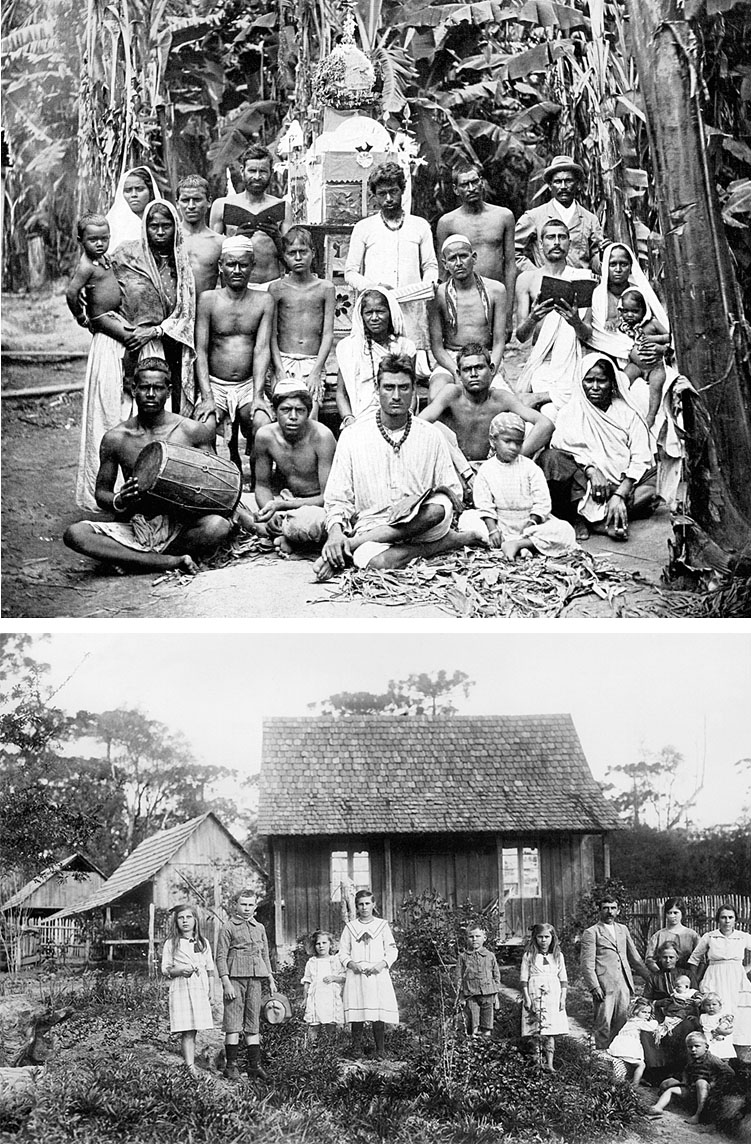

Although Europe was a significant source of immigrants to Latin America, so were Asia and the Middle East. For example, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries large numbers of Japanese arrived in Brazil, most settling in São Paulo state. By 1920 Brazil had the largest Japanese community in the world outside of Japan. From the Middle East, Lebanese, Turks, and Syrians also entered Brazil. Between 1850 and 1880, 144,000 South Asian laborers went to Trinidad, 39,000 to Jamaica, and smaller numbers to the islands of St. Lucia, Grenada, and St. Vincent, mostly as indentured servants under five-

Thanks to the influx of new arrivals, Buenos Aires, São Paulo, Mexico City, Montevideo, Santiago, and Havana experienced spectacular growth. By 1914 Buenos Aires in particular had emerged as one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world, with a population of 3.6 million. As Argentina’s political capital, the city housed its government bureaucracies and agencies. The meatpacking, food-

Immigrants brought wide-

The vast majority of migrants were unmarried males; seven out of ten people who landed in Argentina between 1857 and 1924 were single males between thirteen and forty years old. There, as in other larger South American countries, many of those who stayed married native-