A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 891

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 904

The Turkish Revolution

Days after the end of the First World War, French and then British troops entered Constantinople to begin a five-

But Turkey produced a great leader and revived to become an inspiration to the entire Middle East. Mustafa Kemal (1881–

The sultan, bowing to Allied pressure, initially denounced Kemal, but the cause of national liberation proved more powerful. The catalyst was the Greek invasion and attempted annexation of much of western Turkey. A young Turkish woman described feelings she shared with countless others:

After I learned about the details of the Smyrna occupation by Greek armies, I hardly opened my mouth on any subject except when it concerned the sacred struggle. . . . I suddenly ceased to exist as an individual. I worked, wrote and lived as a unit of that magnificent national madness.3

Refusing to acknowledge the Allied dismemberment of their country, the Turks battled on through 1920 despite staggering defeats. The next year the Greeks advanced almost to Ankara, the nationalist stronghold in central Turkey. There Mustafa Kemal’s forces took the offensive and won a great victory. The Greeks and their British allies sued for peace. The resulting Treaty of Lausanne (1923) abolished the hated capitulations, which since the sixteenth century had given Europeans special privileges in the Ottoman Empire (see “Non-Muslims Under Muslim Rule” in Chapter 17), and recognized a truly independent Turkey. Turkey lost only its former Arab provinces (see Map 29.1).

Mustafa Kemal believed Turkey should modernize and secularize along Western lines. (See “Viewpoints 29.2: Nationalism in Vietnam and Turkey.”) His first moves, beginning in 1923, were political. Drawing on his prestige as a war hero, Kemal called on the National Assembly to depose the sultan and establish a republic. He had himself elected president and moved the capital from cosmopolitan Constantinople (now Istanbul) to Ankara in the Turkish heartland. Kemal savagely crushed the demands for independence of ethnic minorities within Turkey like the Armenians and the Kurds, but he realistically abandoned all thought of winning back lost Arab territories. He then created a one-

Kemal’s most radical changes pertained to religion and culture. For centuries most believers’ intellectual and social activities had been regulated by Islamic religious authorities. Profoundly influenced by the example of western Europe, Mustafa Kemal set out, like the philosophes of the Enlightenment, to limit religious influence in daily affairs, but, like Russia’s Peter the Great, he employed dictatorial measures rather than reason and democracy to reach his goal. Kemal decreed a revolutionary separation of church and state. Secular law codes inspired by European models replaced religious courts. State schools replaced religious schools and taught such secular subjects as science, mathematics, and social sciences.

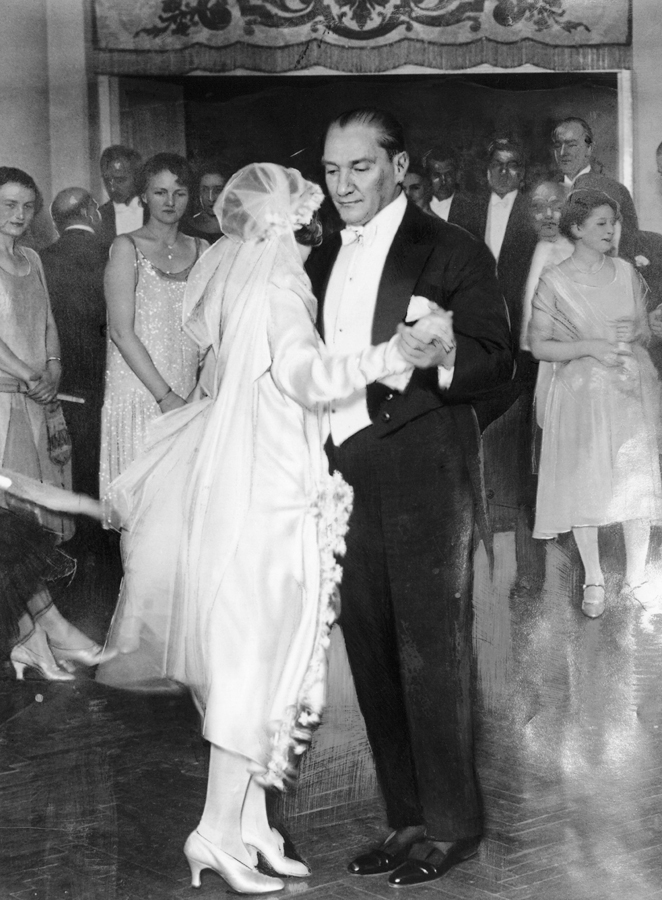

Mustafa Kemal also struck down many entrenched patterns of behavior. Women, traditionally secluded and inferior to males in Islamic society, received the right to vote. Civil law on a European model, rather than the Islamic code, now governed marriage. Women could seek divorces, and no man could have more than one wife at a time. Men were forbidden to wear the tall red fez of the Ottoman era as headgear; government employees were ordered to wear business suits and felt hats, erasing the visible differences between Muslims and “infidel” Europeans. The old Arabic script was replaced with a new Turkish alphabet based on Roman letters, which facilitated massive government efforts to spread literacy after 1928. Finally, in 1935, family names on the European model were introduced. Before this, while Jewish and Christian citizens of the empire had used surnames, Muslim Turks had not. Muslims had generally used a simple formulation of “son of” with their father’s name. The National Assembly granted Mustafa Kemal the surname Atatürk, which means “father of the Turks.”

By his death in 1938, Atatürk and his supporters had consolidated their revolution. Government-