A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 896

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 908

Arab-Jewish Tensions in Palestine

Relations between the Arabs and the West were complicated by the tense situation in the British mandate of Palestine, and that situation deteriorated in the interwar years. Both Arabs and Jews denounced the British, who tried unsuccessfully to compromise with both sides. Arab nationalist anger, however, was aimed primarily at Jewish settlers. The key issue was Jewish migration from Europe to Palestine.

A small Jewish community had survived in Palestine ever since the dispersal of the Jews in Roman times. But Jewish nationalism, known as Zionism, took shape in Europe in the late nineteenth century under Theodor Herzl’s leadership (see “Jewish Emancipation and Modern Anti-Semitism” in Chapter 24). Herzl believed only a Jewish state could guarantee Jews dignity and security. The Zionist movement encouraged some of the world’s Jews to settle in Palestine, but until 1921 the great majority of Jewish emigrants preferred the United States.

After 1921 the situation changed radically. An isolationist United States drastically limited immigration from eastern Europe, where war and revolution had kindled anti-

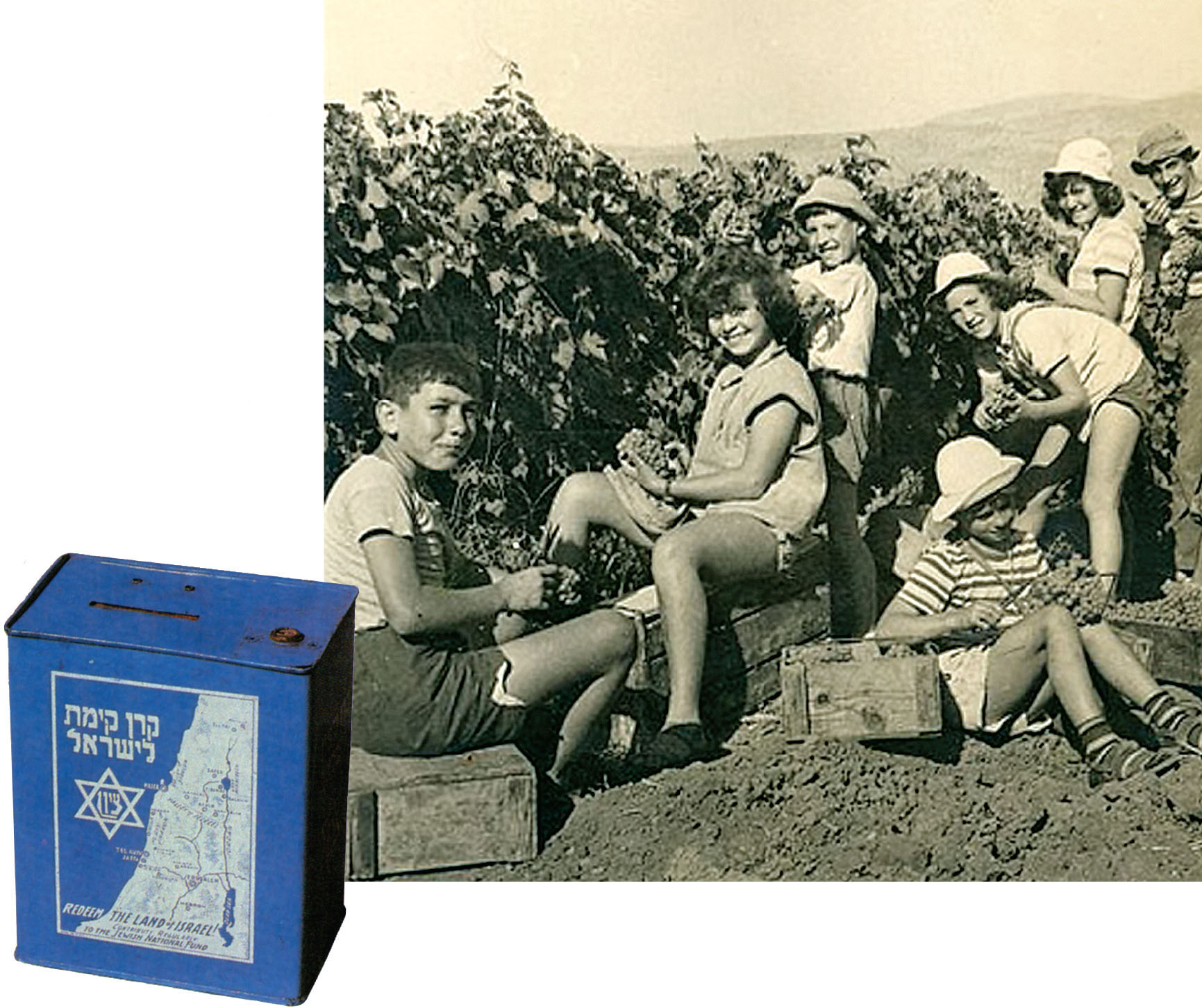

Jewish settlers in Palestine faced formidable difficulties. Although much of the land purchased by the Jewish National Fund was productive, the sellers of such land were often wealthy absentee Arab landowners who cared little for their Arab tenants’ welfare. When the new Jewish owners replaced those long-

The British gradually responded to Arab pressure and tried to slow Jewish immigration. This effort satisfied neither Jews nor Arabs, and by 1938 the two communities were engaged in an undeclared civil war. Jewish and Arab armed militias attacked each other, and both attacked British police and military forces. Massacres were committed by both Arabs and Jews, viewed by one side as necessary for the freedom struggle, and by the other side as terrorist acts.

On the eve of the Second World War, the frustrated British proposed an independent Palestine with the number of Jews permanently limited to only about one-

Nevertheless, in the face of adversity Jewish settlers from many different countries gradually succeeded in forging a cohesive community in Palestine. Hebrew, for centuries used only in religious worship, was revived as a living language in the 1920s–