A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 38

Listening to the Past

Gilgamesh’s Quest for Immortality

Listening to the Past

Gilgamesh’s Quest for Immortality

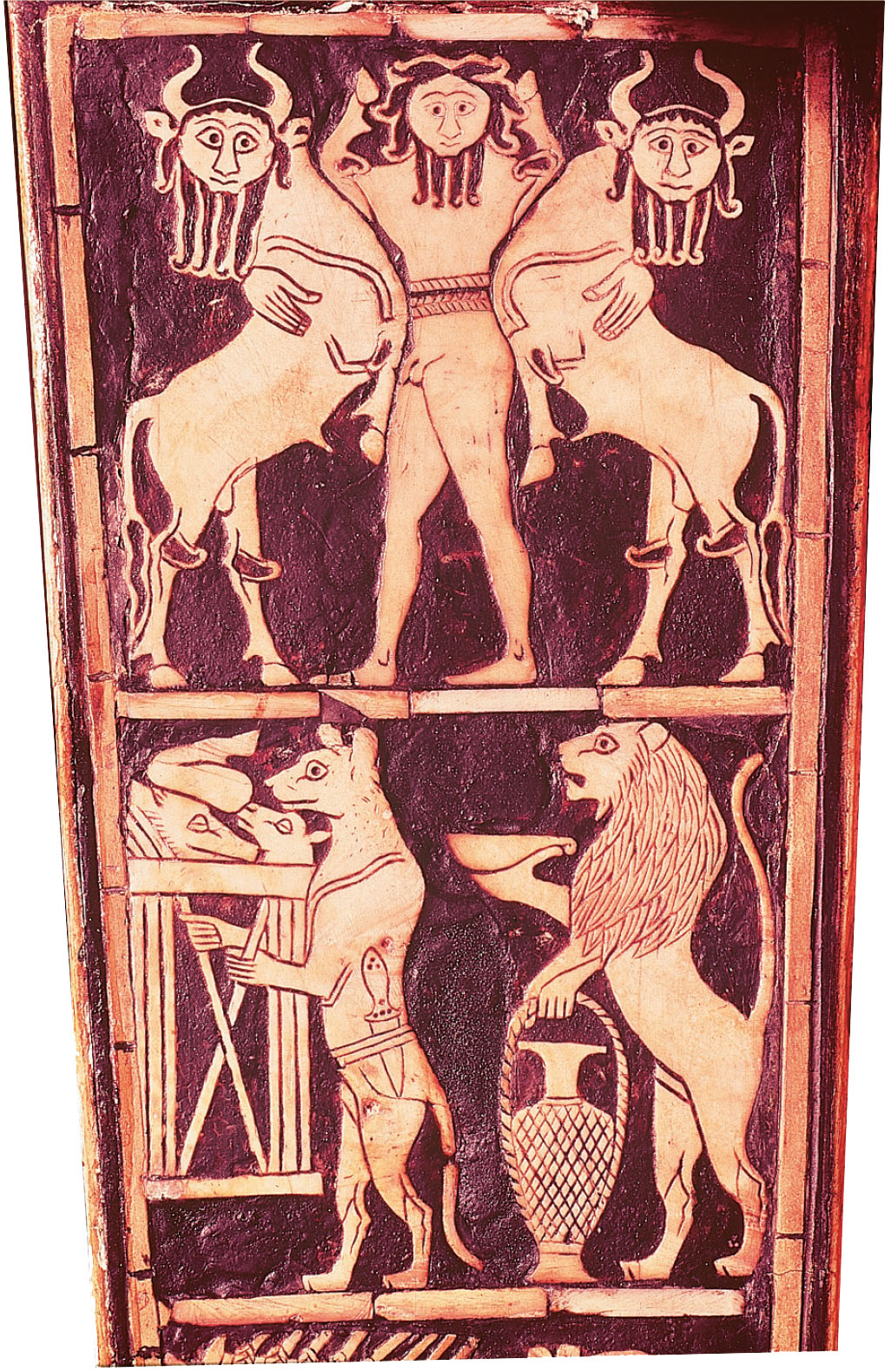

The human desire to escape the grip of death appears in many cultures. The Epic of Gilgamesh is perhaps the earliest recorded treatment of this topic. The oldest elements of the epic go back to stories told in the third millennium B.C.E. According to tradition, Gilgamesh was a king of the Sumerian city of Uruk. In the story, Gilgamesh is not fulfilling his duties as the king very well and sets out with his friend Enkidu to perform wondrous feats against fearsome agents of the gods. Together they kill several supernatural beings, and the gods decide that Enkidu must die. He foresees his own death in a dream.

“Listen again, my friend [Gilgamesh]! I had a dream in the night.

The sky called out, the earth replied,

I was standing in between them.

There was a young man, whose face was obscured.

His face was like that of an Anzu-

He had the paws of a lion, he had the claws of an eagle.

He seized me by my locks, using great force against me. . . .

He seized me, drove me down to the dark house, dwelling of Erkalla’s god [the underworld], . . .

On the road where travelling is one way only,

To the house where those who stay are deprived of light. . . .”

Enkidu sickens and dies. Gilgamesh is distraught and determined to become immortal. He decides to journey to Ut-

“How could my cheeks not be wasted, nor my face dejected,

Nor my heart wretched, nor my appearance worn out,

Nor grief in my innermost being,

Nor my face like that of a long-

Nor my face weathered by wind and heat

Nor roaming open country clad only in a lionskin?

My friend was the hunted mule, wild ass of the mountain, leopard of open country,

Enkidu my friend was the hunted mule, wild ass of the mountain, leopard of open country.

We who met, and scaled the mountain,

Seized the Bull of Heaven [the sacred bull of the goddess Ishtar] and slew it,

Demolished Humbaba [the ogre who guards the forest of the gods] who dwelt in the Pine Forest,

Killed lions in the passes of the mountains,

My friend whom I love so much, who experienced every hardship with me,

Enkidu my friend whom I love so much, who experienced every hardship with me —

The fate of mortals conquered him!

For six days and seven nights I wept over him: I did not allow him to be buried

Until a worm fell out of his nose.

I was frightened and

I am afraid of Death, and so I roam open country.

The words of my friend weigh upon me. . . .

I roam open country on long journeys.

How, O how could I stay silent, how, O how could I keep quiet?

My friend whom I love has turned to clay: Enkidu my friend whom I love has turned to clay.

Am I not like him? Must I lie down too,

Never to rise, ever again?”

Gilgamesh finally reaches Ut-

“Why do you prolong grief, Gilgamesh?

Since [the gods made you] from the flesh of gods and mankind,

Since [the gods] made you like your father and mother

[Death is inevitable] . . . ,

Nobody sees the face of Death,

Nobody hears the voice of Death.

Savage Death just cuts mankind down.

Sometimes we build a house, sometimes we make a nest,

But then brothers divide it upon inheritance.

Sometimes there is hostility in [the land],

But then the river rises and brings flood-

The Anunnaki, the great gods, assembled;

Mammitum [the great mother goddess] who creates fate decreed destinies with them.

They appointed death and life.

They did not mark out days for death,

But they did so for life.”

Gilgamesh asks Ut-

“Go up on to the wall of Uruk, Ur-

Inspect the foundation platform and scrutinize the brickwork! Testify that its bricks are baked bricks,

And that the Seven Counsellors must have laid its foundations!

One square mile is city, one square mile is orchards, one square mile is claypits, as well as the open ground of Ishtar’s temple.

Three square miles and the open ground comprise Uruk.”

Source: Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, trans. Stephanie Dalley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), pp. 88–

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- What does the Epic of Gilgamesh reveal about Sumerian attitudes toward the gods and human beings?

- What does the epic tell us about Sumerian views of the nature of human life? Where do human beings fit into the cosmic world?

- At the end of his quest, did Gilgamesh achieve immortality? If so, what was the nature of that immortality?