A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 46

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 43

Chapter Chronology

Migrations, Revivals, and Collapse

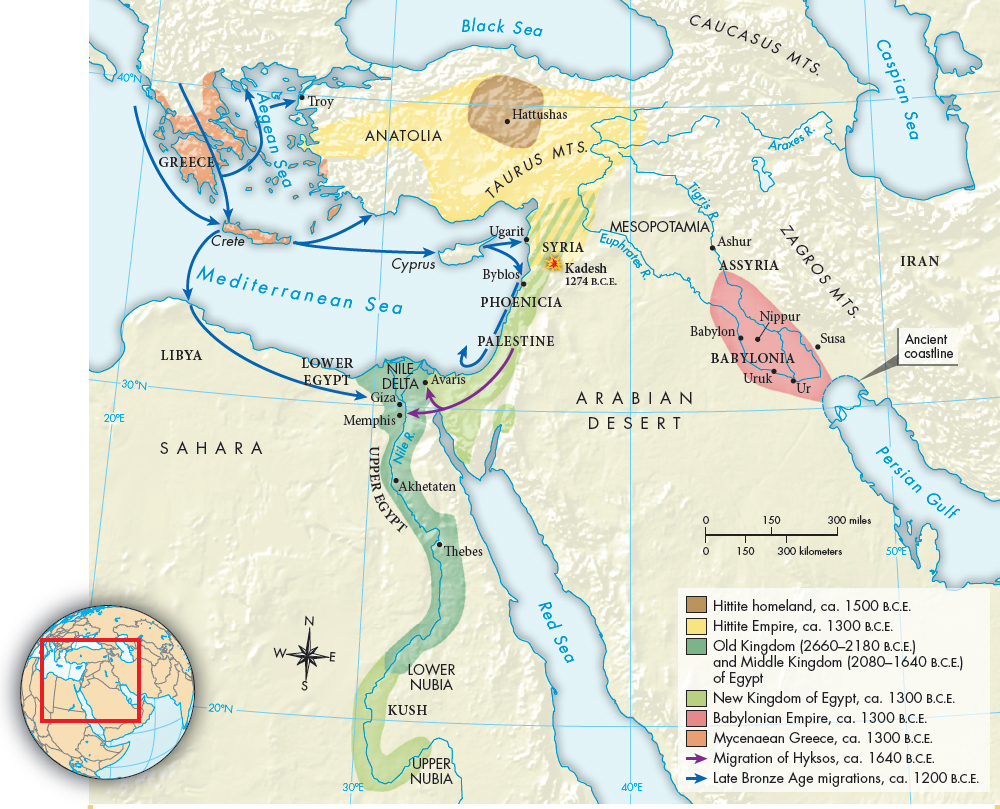

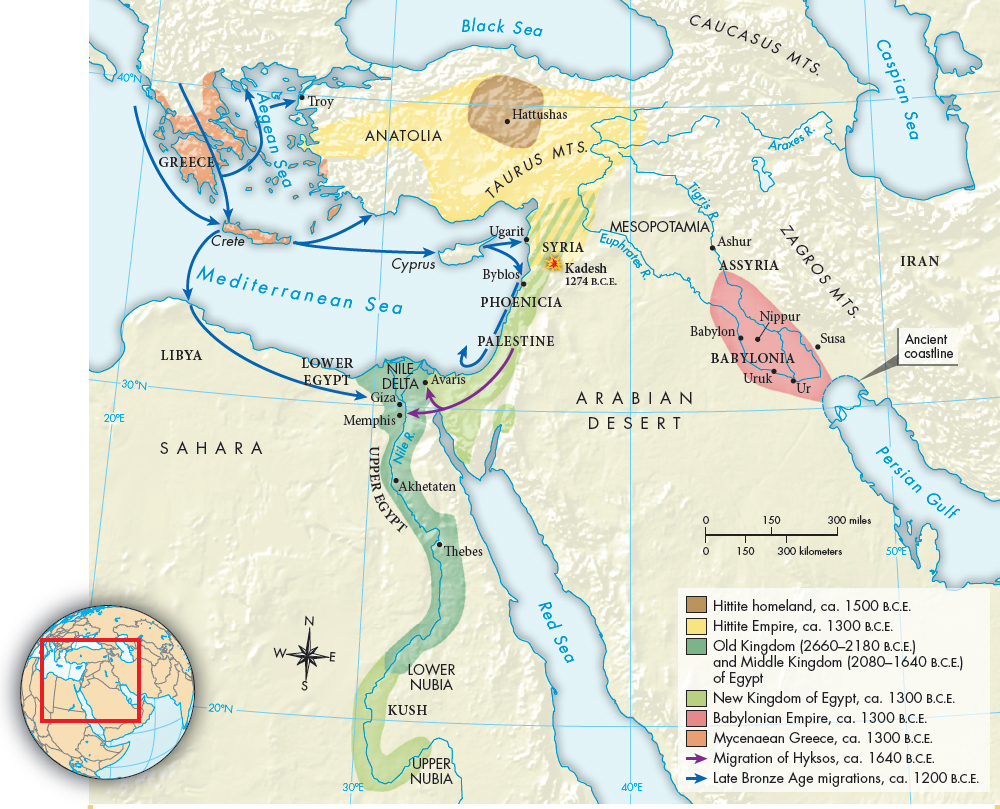

While Egyptian civilization flourished in the Nile Valley, various groups migrated throughout the Fertile Crescent and then accommodated themselves to local cultures (see Map 2.2). Some settled in the Nile Delta, including a group the Egyptians called Hyksos, meaning “rulers of the uplands.” Although they were later portrayed as a conquering horde, the Hyksos were actually migrants looking for good land, and their entry into the delta, which began around 1800 B.C.E., was probably gradual and generally peaceful. The newcomers began to worship Egyptian deities and modeled their political structures on those of the Egyptians.

Mapping the PastMAP 2.2 Empires and Migrations in the Eastern Mediterranean The rise and fall of empires in the eastern Mediterranean were shaped by internal developments, military conflicts, and the migration of peoples to new areas.ANALYZING THE MAP At what point was the Egyptian Empire at its largest? The Hittite Empire? What were the other major powers in the eastern Mediterranean at this time?CONNECTIONS What were the major effects of the migrations of the Hyksos? Of the late Bronze Age migrations? What clues does the map provide as to why the late Bronze Age migrations had a more powerful impact than those of the Hyksos?

The Hyksos brought with them methods of making bronze (see Chapter 1) and casting it into weapons that became standard in Egypt. They thereby brought Egypt fully into the Bronze Age culture of the Mediterranean world. The Hyksos also introduced horse-drawn chariots and the composite bow, made of multiple materials for greater strength, which along with bronze weaponry revolutionized Egyptian warfare. The migration of the Hyksos, combined with a series of famines and internal struggles for power, led Egypt to fragment politically in what later came to be known as the Second Intermediate Period.

In about 1570 B.C.E. a new dynasty of pharaohs arose, pushing the Hyksos out of the delta and conquering territory to the south and northeast. These warrior-pharaohs inaugurated what scholars refer to as the New Kingdom, a period characterized not only by enormous wealth and conscious imperialism but also by a greater sense of insecurity because of new contacts and military engagements. By expanding Egyptian power beyond the Nile Valley, the pharaohs created the first Egyptian empire, and they celebrated their triumphs with monuments on a scale unparalleled since the pyramids of the Old Kingdom. Their giant statues and rich tombs might also indicate an expansion of imported slave labor, although some scholars are rethinking the extent of slave labor in the New Kingdom.

The New Kingdom pharaohs include a number of remarkable figures. Among these was Hatshepsut (haht-SHEP-soot) (r. ca. 1479–ca. 1458 B.C.E.), one of the few female pharaohs in Egypt’s long history who seized the throne for herself and used her reign to promote building and trade. (See “Individuals in Society: Hatshepsut and Nefertiti.”) Amenhotep III (ah-men-HOE-tep) (r. ca. 1388–ca. 1350 B.C.E.) corresponded with other powerful kings in Babylonia and other kingdoms in the Fertile Crescent, sending envoys, exchanging gifts, making alliances, and in some cases marrying their daughters. Amenhotep III was succeeded by his son, who took the name Akhenaten (ah-keh-NAH-tuhn) (r. 1351–1334 B.C.E.). He renamed himself as a mark of his changing religious ideas, choosing to worship a new sun-god, Aten, instead of the traditional Amon or Ra. He was not a monotheist — someone who worships only one god — but he did order the erasure of the names of other sun-gods from the walls of buildings, the transfer of taxes from the traditional priesthood of Amon-Ra, and the building of huge new temples to Aten. Akhenaten’s wife Nefertiti (nehf-uhr-TEE-tee) supported his religious ideas, but this new religion, imposed from above, failed to find a place among the people, and after his death traditional religious practices returned.

Hittite Archer in a Chariot In this stylized stone carving made about 1000 B.C.E. in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), a Hittite archer driven in a chariot shoots toward his foes, while a victim of an earlier shot is trampled beneath the horse’s hooves. The arrows might have been tipped with iron, which was becoming a more common material for weapons and tools. (Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey/Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY)

One of the key challenges facing the pharaohs after Akhenaten was the expansion of the kingdom of the Hittites. At about the same time that the Sumerians were establishing city-states, speakers of Indo-European languages migrated into Anatolia, modern-day Turkey. Indo-European is a large family of languages that includes English, most of the languages of modern Europe, ancient Greek, Latin, Persian, Hindi, Bengali, and Sanskrit (for more on Sanskrit, see “The Aryans During the Vedic Age, ca. 1500-500 B.C.E.” in Chapter 3). It also includes Hittite, the language of one of the peoples who migrated into this area. Information about the Hittites comes from archaeological sources and also from written cuneiform tablets that provide details about politics and economic life. These records indicate that beginning about 1600 B.C.E., Hittite kings began to conquer more territory (see Map 2.2). As the Hittites expanded southward, they came into conflict with the Egyptians, who were establishing their own larger empire. There were a number of battles, but both sides seem to have recognized the impossibility of defeating the other, and in 1258 the Egyptian king Ramesses II (r. ca. 1290–1224 B.C.E.) and the Hittite king Hattusili III (r. ca. 1267–1237 B.C.E.) concluded a peace treaty, which was recorded in both Egyptian hieroglyphics and Hittite cuneiform.

The treaty brought peace between the Egyptians and the Hittites for a time, but this stability did not last. Within several decades of the treaty, groups of seafaring peoples whom the Egyptians called “Sea Peoples” raided, migrated, and marauded in the eastern Mediterranean, disrupting trade and in some cases looting and destroying cities. Just who these people were and where they originated is much debated among scholars, but their raids, combined with the expansion of the Assyrians (see “The Assyrians and Persians”), led to the collapse of the Hittite Empire and the fragmentation of the Egyptian empire in what historians later termed the Third Intermediate Period (1100–653 B.C.E.). There is evidence of drought, and some scholars have suggested that a major volcanic explosion in Iceland cooled the climate for several years, leading to a series of poor harvests. All of these developments are part of a general “Bronze Age Collapse” in the period around 1200 B.C.E. that historians see as a major turning point.

The political and military story of battles, waves of migrations, and the rise and fall of empires can mask striking continuities in the history of Egypt and its neighbors. Disrupted peoples and newcomers shared practical concepts of agriculture and metallurgy with one another, and wheeled vehicles allowed merchants to transact business over long distances. Merchants, migrants, and conquerors carried their gods and goddesses with them, and religious beliefs and practices blended and changed. Cuneiform tablets, wall inscriptions, and paintings testify to commercial exchanges and cultural accommodation, adoption, and adaptation.