A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 50

Global Trade

Iron has shaped world history more than any other metal, even more than gold and silver. In its pure state iron is soft, but adding small amounts of carbon and various minerals, particularly at very high temperatures, transforms it into a material with great structural strength. Tools and weapons made of iron dramatically shaped interactions between peoples in the ancient world, and machines made of iron and steel literally created the modern world.

Human use of iron began during the Paleolithic era, when people living in what is now Egypt used small pieces of hematite, a type of iron oxide, as part of their tools, along with stone, bone, and wood. Beginning around 4000 B.C.E. people in several parts of the world began to pick up iron-

Iron is the most common element in the earth, but most iron on or near the earth’s surface occurs in the form of ore, which must be smelted to extract the metal. This is also true of copper and tin, but these can be smelted at much lower temperatures than iron, so they were the first metals to be produced to any great extent and were usually mixed together to form bronze. As artisans perfected bronze metalworking techniques, they also experimented with iron. They developed a long and difficult process to smelt iron, using burning charcoal and a bellows (which raised the temperature further) to extract the iron from the ore. This was done in an enclosed furnace, and the process was repeated a number of times as the ore was transformed into wrought iron, which could be formed into shapes.

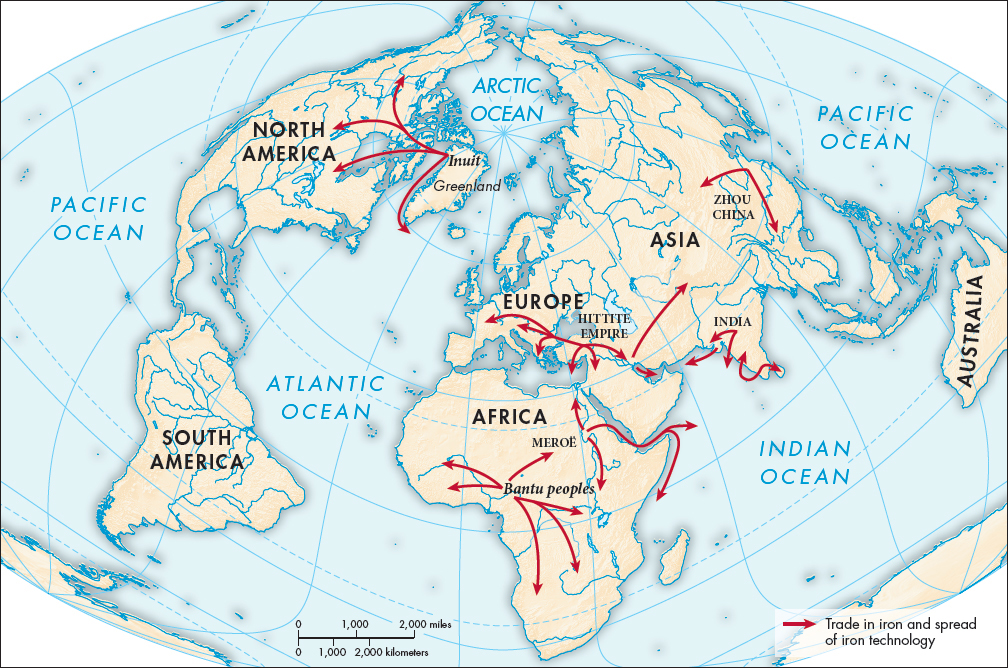

Exactly where and when the first smelted iron was produced is a matter of debate — many places would like to have this honor — but it happened independently in several different places. In Anatolia (modern-

Smelting was discovered independently in what is now Nigeria in western Africa about 1500 B.C.E. by a group of people who spoke Bantu languages. They carried iron hoes, axes, shovels, and weapons, and the knowledge of how to make them, as they migrated south and east over many centuries, gave them a distinct advantage over foraging peoples. In East Africa, the Kushite people learned the advantages of iron weaponry when the iron-

Ironworkers continued to experiment and improve their products. The Chinese probably learned smelting from Central Asian steppe peoples, but in about 500 B.C.E. artisans in China developed techniques of making cast iron using molds, whereby implements could be made much more efficiently. Somewhere in the Near East ironworkers discovered that if the relatively brittle wrought iron objects were placed on a bed of burning charcoal and then cooled quickly, the outer layer would form into a layer of a much harder material, steel. Goods made of cast iron were usually traded locally because they were heavy, but fine sword and knife blades of steel traveled long distances, and the knowledge of how to make them followed.