A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 56

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 53

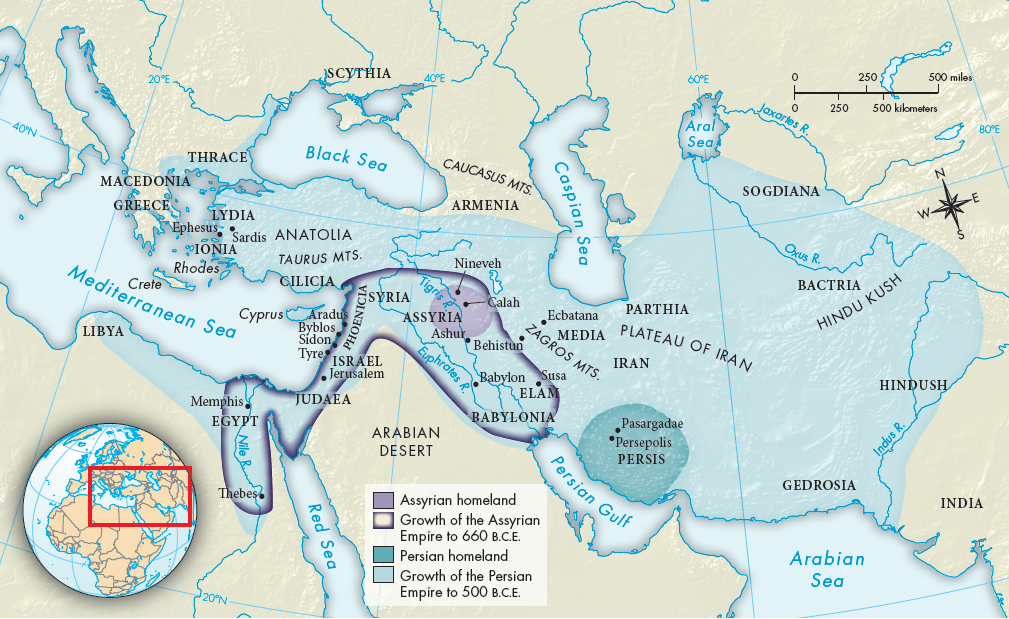

The Rise and Expansion of the Persian Empire

As we have seen, Assyria rose to power from a base in the Tigris and Euphrates River Valleys of Mesopotamia, which had seen many earlier empires. The Assyrians were defeated by a coalition that included not only a Mesopotamian power — Babylon — but also a people with a base of power in a part of the world that had not been the site of earlier urbanized states: Persia (modern-

Iran’s geographical position and topography explain its traditional role as the highway between western and eastern Asia. Nomadic peoples migrating south from the broad steppes of Russia and Central Asia have streamed into Iran throughout much of history. (For an in-

Among these nomads were Indo-

In 550 B.C.E. Cyrus the Great (r. 559–

After his victories, Cyrus made sure the Persians were portrayed as liberators, and in some cases he was more benevolent than most conquerors. According to later Greek sources, he spared the life of the conquered king of Lydia, Croesus, who then became his adviser. According to his own account, he freed all the captive peoples, including the Hebrews, who were living in forced exile in Babylon. He returned the Hebrews’ sacred objects to them and allowed those who wanted to do so to return to Jerusalem, where he paid for the rebuilding of their temple. (See “Viewpoints 2.2: Rulers and Divine Favor: Cyrus the Great in the Cyrus Cylinder and Hebrew Scripture.”)

Cyrus’s successors continued the Persian conquests, creating the largest empire the world had yet seen. Darius (r. 521–

The Persians also knew how to preserve the peace they had won on the battlefield. To govern the empire, they created an efficient administrative system based in their newly built capital city of Persepolis, near modern Shiraz, Iran. Under Darius, they divided the empire into districts and appointed either Persian or local nobles as administrators called satraps to head each one. The satrap controlled local government, collected taxes, heard legal cases, and maintained order. He was assisted by a council and also by officials and army leaders sent from Persepolis who made sure that he knew the will of the king and that the king knew what was going on in the provinces. This system decreased opposition to Persian rule by making local elites part of the system of government, although sometimes satraps used their authority to build up independent power. The Persians allowed the peoples they conquered to maintain their own customs and beliefs as long as they paid the proper amount of taxes and did not rebel. Their rule resulted in an empire that brought people together in a new political system, with a culture that blended older and newer religious traditions and ways of seeing the world.

Communication and trade were eased by a sophisticated system of roads linking the empire from the coast of Asia Minor to the valley of the Indus River. These roads meant that the king was usually in close touch with officials and subjects, and they simplified the defense of the empire by making it easier to move Persian armies. The roads also aided the flow of trade, which Persian rulers further encouraged by building canals, including one that linked the Red Sea and the Nile.

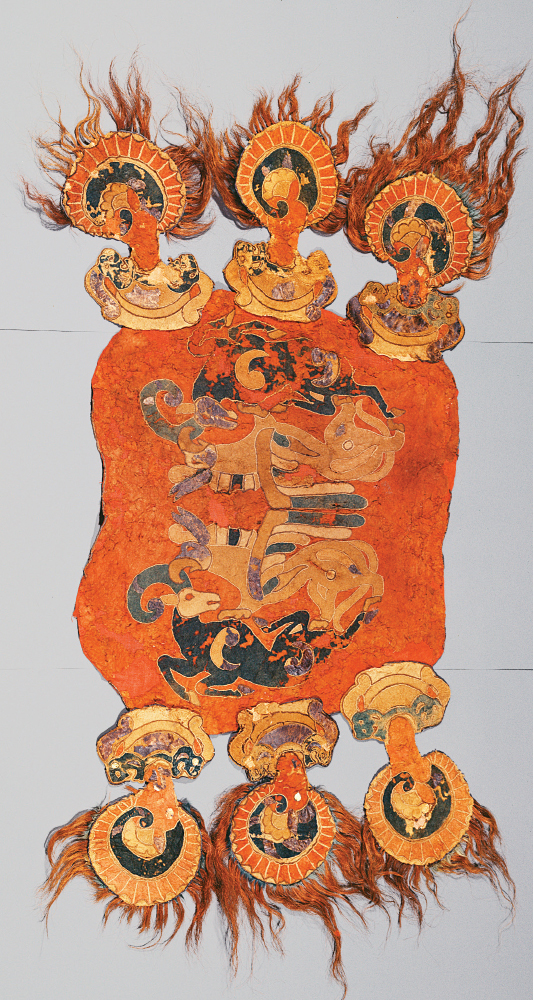

The Persians made significant contributions to art and culture. In art they transformed the Assyrian tradition of realistic monumental sculpture from one that celebrated gory details of slaughter to one that showed both the Persians and their subjects as dignified. Because they depicted both themselves and non-