A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 32

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 31

Chapter Chronology

Written Sources and the Human Past

Writing is closely tied to the idea of history itself. The term history comes from the Greek word historia, coined by Herodotus (hi-ROD-duh-tuhs) (ca. 484–ca. 425 B.C.E.) in the fifth century B.C.E. to describe his inquiry into the past. As Herodotus used them, the words inquiry and history are the same. Herodotus based his Histories, at their core a study of the origins of the wars between the Persians and the Greeks that occurred about the time he was born, on the oral testimony of people he had met as he traveled. Many of these people had been participants in the wars, and Herodotus was proud that he could rely so much on the eyewitness accounts of the people involved. Today we call this methodology “oral history,” and it remains a vital technique for studying the recent past. Following the standard practice of the time, Herodotus most likely read his Histories out loud at some sort of public gathering. Herodotus also wrote down his histories and consulted written documents. From his day until quite recently, this aspect of his methods has defined history and separated it from prehistory: history came to be regarded as the part of the human past for which there are written records. In this view, history began with the invention of writing in the fourth millennium B.C.E. in a few parts of the world.

As noted in Chapter 1, this line between history and prehistory has largely broken down. Historians who study human societies that developed systems of writing continue to use many of the same types of physical evidence as do those who study societies without writing. For some cultures, the writing or record-keeping systems have not yet been deciphered, so our knowledge of these people also depends largely on physical evidence. Scholars can read the writing of a great many societies, however, adding greatly to what we can learn about them.

Much ancient writing survives only because it was copied and recopied, sometimes years after it was first produced. The oldest known copy of Herodotus’s Histories, for example, dates from about 900 C.E., nearly a millennium and a half after he finished this book. The survival of a work means that someone from a later period — and often a long chain of someones — judged it worthy of the time, effort, and resources needed to produce copies. The copies may not be completely accurate, either because the scribe made an error or because he (or, much less often, she) decided to change something. Historians studying ancient works thus often try to find as many early copies as they can and compare them to arrive at the version they think is closest to the original.

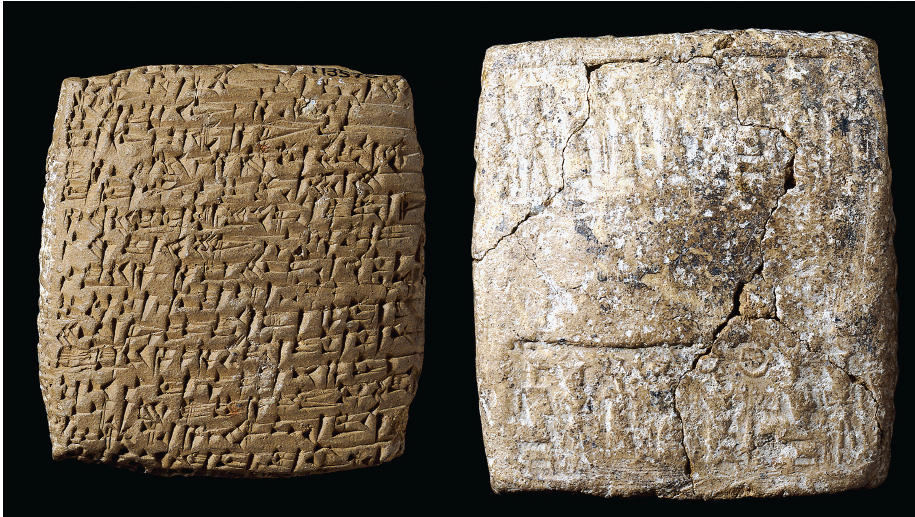

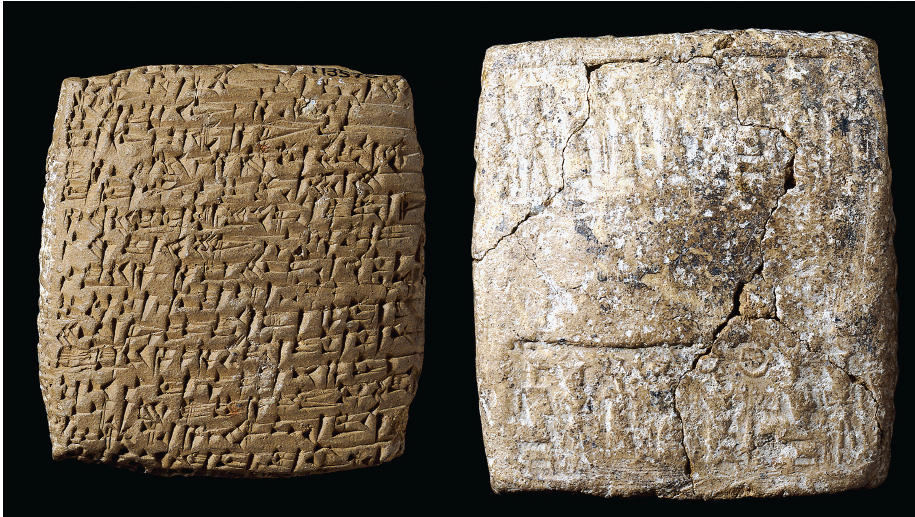

Clay Letter Written in Cuneiform and Its Envelope, ca. 1850 B.C.E. In this letter from a city in Anatolia, located on the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent in what is now southern Turkey, a Mesopotamian merchant complains to his brother at home, hundreds of miles away, that life is hard and comments on the trade in silver, gold, tin, and textiles. Correspondents often enclosed letters in clay envelopes and sealed them by rolling a cylinder seal across the clay, leaving the impression of a scene, just as you might use a stamped wax seal today. Here the very faint impression of the sender’s seal at the bottom shows a person, probably the owner of the seal, being led in a procession toward a king or god. (© The Trustees of the British Museum/Art Resource, NY)

The works considered worthy of copying tend to be those that, like the Histories, are about the political and military events involving major powers, those that record religious traditions, or those that come from authors who were later regarded as important. By contrast, written sources dealing with the daily life of ordinary men and women were few to begin with and were rarely saved or copied because they were not considered significant.

Some early written texts survive in their original form because people inscribed them in stone, shells, bone, or other hard materials, intending them to be permanent. Stones with inscriptions were often erected in the open in public places for all to see, so they include text that leaders felt had enduring importance, such as laws, religious proclamations, decrees, and treaties. (The names etched in granite on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., are perhaps the best-known modern example, but inscriptions can be found on nearly every major public building.) Sometimes this permanence was accidental: in ancient Mesopotamia (in the area of modern Iraq), all writing was initially made up of indentations on soft clay tablets, which then hardened. Hundreds of thousands of these tablets have survived, the oldest dating to about 3200 B.C.E., and from them historians have learned about many aspects of everyday life. By contrast, writing in Egypt at the same time was often done in ink on papyrus sheets, made from a plant that grows abundantly in Egypt. Some of these papyrus sheets have survived, but papyrus is much more fragile than hardened clay, so most have disintegrated. In China, the oldest surviving writing is on bones and turtle shells from about 1200 B.C.E., but it is clear that writing was done much earlier on less permanent materials such as silk and bamboo. (For more on the origins of Chinese writing, see “The Development of Writing” in Chapter 4.)

However they have survived and however limited they are, written records often become scholars’ most important original sources for investigating the past. Thus the discovery of a new piece of written evidence from the ancient past — such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, which contain sections of the Hebrew Bible and were first seen by scholars in 1948 — is always a major event. But reconstructing and deciphering what are often crumbling documents can take decades, and disputes about how these records affect our understanding of the past can go on forever.