A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 928

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 938

Chapter Chronology

The Five-Year Plans

The 1927 party congress marked the end of the NEP and the beginning of socialist five-year plans. The first five-year plan had staggering economic objectives. In just five years, total industrial output was to increase by 250 percent and agricultural production by 150 percent. By 1930 economic and social change was sweeping the country in a frenzied effort to modernize, much like the Industrial Revolution in Europe in the 1800s (see Chapter 23), and dramatically changing the lives of ordinary people, sometimes at great personal cost. One worker complained, “The workers . . . made every effort to fulfill the industrial and financial plan and fulfilled it by more than 100 percent, but how are they supplied? The ration is received only by the worker, except for rye flour, his wife and small children receive nothing. Workers and their families wear worn-out clothes, the kids are in rags, their naked bellies sticking out.”6

Stalin unleashed his “second revolution” because, like Lenin, Stalin and his militant supporters were deeply committed to socialism as they understood it. Stalin was also driven to catch up with the advanced and presumably hostile Western capitalist nations. To a conference of managers of socialist industry in February 1931, Stalin famously declared:

It is sometimes asked whether it is not possible to slow down the tempo a bit, to put a check on the movement. No, comrades, it is not possible! The tempo must not be reduced! . . . To slacken the tempo would mean falling behind. And those who fall behind get beaten. But we do not want to be beaten. No, we refuse to be beaten! . . . We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in ten years. Either we do it, or we shall be crushed.7

Domestically, there was the peasant problem. For centuries peasants had wanted to own the land, and finally they had it. Sooner or later, the Communists reasoned, the peasants would become conservative capitalists and threaten the regime. Stalin therefore launched a preventive war against the peasantry to bring it under the state’s absolute control.

That war was collectivization — the forcible consolidation of individual peasant farms into large, state-controlled enterprises. Beginning in 1929 peasants were ordered to give up their land and animals and become members of collective farms. As for the kulaks, the better-off peasants, Stalin instructed party workers to “break their resistance, to eliminate them as a class.”8 Stripped of land and livestock, many starved or were deported to forced-labor camps for “re-education.”

Since almost all peasants were poor, the term kulak soon meant any peasant who opposed the new system. Whole villages were often attacked. One conscience-stricken colonel in the secret police confessed to a foreign journalist:

I am an old Bolshevik. I worked in the underground against the Tsar and then I fought in the Civil War. Did I do all that in order that I should now surround villages with machine guns and order my men to fire indiscriminately into crowds of peasants? Oh, no, no!9

Forced collectivization led to disaster. Many peasants slaughtered their animals and burned their crops in protest. Nor were the state-controlled collective farms more productive. Grain output barely increased, and collectivized agriculture made no substantial financial contribution to Soviet industrial development during the first five-year plan.

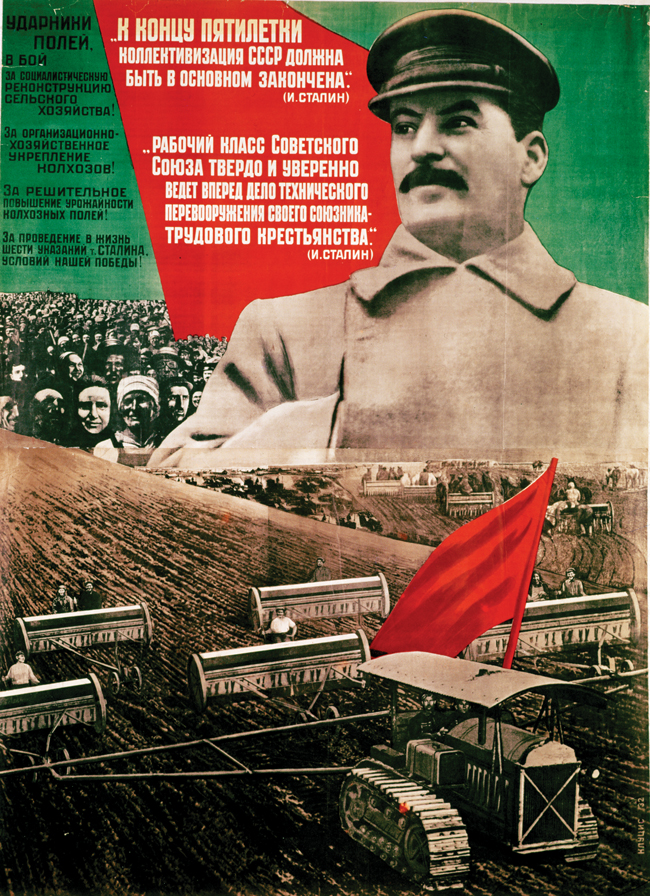

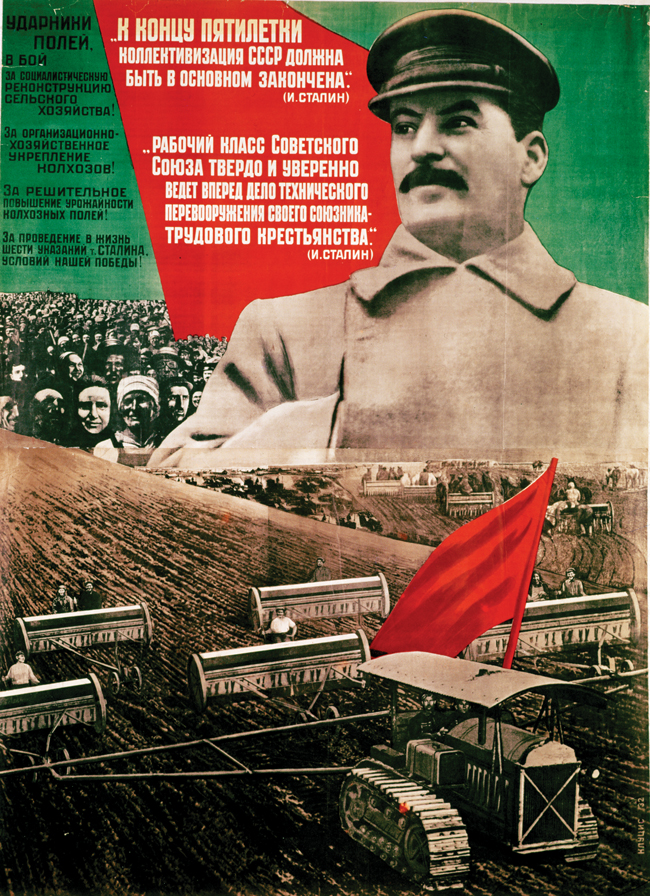

Soviet Collectivization Poster Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ordered a nationwide forced collectivization campaign from 1929 to 1933. Following communist theory, the government created large-scale collective farms by seizing land and forcing peasants to work on it. In this idealized 1932 poster, farmers are encouraged to complete the five-year plan of collectivization, while Stalin looks on approvingly. The outcome instead was a disaster. Millions of people died in the resulting human-created famine. (Deutsches Plakat Museum, Essen, Germany/Archives Charmet/The Bridgeman Art Library)

In Ukraine Stalin instituted a policy of all-out collectivization with two goals: to destroy all expressions of Ukrainian nationalism, and to break the Ukrainian peasants’ will so they would accept collectivization and Soviet rule. Stalin began by purging Ukraine of its intellectuals and political elite, labeling them reactionary nationalists and enemies of socialism. He then set impossibly high grain quotas — up to nearly 50 percent of total production — for the collectivized farms. This grain quota had to be turned over to the government before any peasant could receive a share. Many scholars and dozens of governments and international organizations have declared Stalin’s and the Soviet government’s policies a deliberate act of genocide. As one historian observed:

Grain supplies were sufficient to sustain everyone if properly distributed. People died mostly of terror-starvation (excess grain exports, seizure of edibles from the starving, state refusal to provide emergency relief, bans on outmigration, and forced deportation to food-deficit locales), not poor harvests and routine administrative bungling.10

The result was a terrible man-made famine, called in Ukrainian the Holodomor (Hunger-extermination), in Ukraine in 1932 and 1933, which probably claimed 3 to 5 million lives.

Collectivization was a cruel but real victory for Communist ideologues who were looking to institute their brand of communism and to crush opposition as much as improve production. By 1938, 93 percent of peasant families had been herded onto collective farms at a horrendous cost in both human lives and resources. Regimented as state employees and dependent on the state-owned tractor stations, the collectivized peasants were no longer a political threat.

The industrial side of the five-year plans was more successful. Soviet industry produced about four times as much in 1937 as in 1928. No other major country had ever achieved such rapid industrial growth. Heavy industry led the way, and urban development accelerated: more than 25 million people migrated to cities to become industrial workers during the 1930s.

The sudden creation of dozens of new factories demanded tremendous resources. Funds for industrial expansion were collected from the people through heavy hidden sales taxes. Firm labor discipline also contributed to rapid industrialization. Trade unions lost most of their power, and individuals could not move without police permission. When factory managers needed more hands, they were sent “unneeded” peasants from collective farms.

Foreign engineers were hired to plan and construct many of the new factories. Highly skilled American engineers, hungry for work in the depression years, were particularly important until newly trained Soviet experts began to replace them after 1932. Siberia’s new steel mills were modeled on America’s best. Thus Stalin’s planners harnessed the skill and technology of capitalist countries to promote the surge of socialist industry.