A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 964

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 976

Independence in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh

World War II accelerated the drive toward Indian independence begun by Mohandas Gandhi (see “The Roots of Militant Nonviolence” in Chapter 29). In 1942 Gandhi called on the British to “quit India” and threatened another civil disobedience campaign. He and the other Indian National Congress Party leaders were soon after arrested and were jailed for much of the war. Thus India’s wartime support for Britain was substantial but not always enthusiastic. Meanwhile, the Congress Party’s prime rival skillfully seized the opportunity to increase its influence.

The Congress Party’s rival was the Muslim League, led by the English-

The Hindus and Muslims have two different religions, philosophies, social customs, literatures. They neither inter-

Gandhi regarded Jinnah’s two-

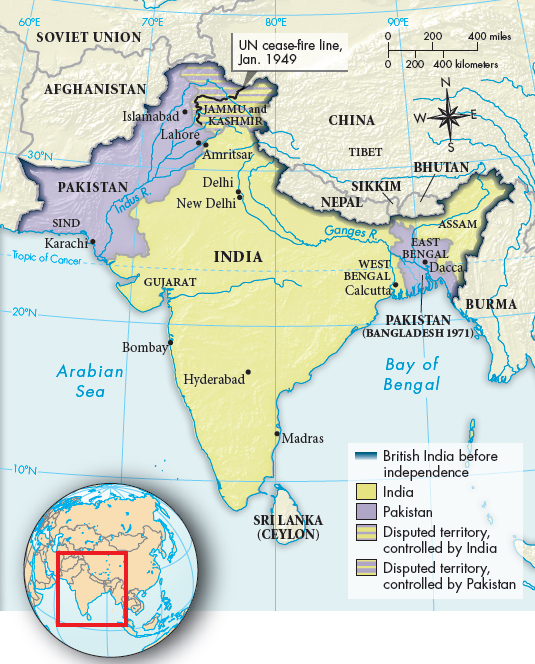

Britain agreed to speedy independence for India after 1945, but conflicts between Hindu and Muslim nationalists led to murderous clashes in 1946. When it became clear that Jinnah and the Muslim League would accept nothing less than an independent state of Pakistan, India’s last colonial viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, mediated a partition that created a predominantly Hindu nation and a predominantly Muslim nation. On August 14, 1947, India and Pakistan gained political independence from Britain as two separate nations (Map 31.2).

Massacres and mass expulsions followed independence. Perhaps a hundred thousand Hindus and Muslims were slaughtered, and an estimated 5 million became refugees. Congress Party leaders were completely powerless to stop the wave of violence. “What is there to celebrate?” exclaimed Gandhi in reference to independence, “I see nothing but rivers of blood.”6 Gandhi labored to ease tensions between Hindus and Muslims, but in the aftermath of riots in January 1948, he was killed by a Hindu gunman who resented what he saw as Gandhi’s appeasement of Muslims.

After the ordeal of independence, relations between India and Pakistan remained tense. Fighting over the disputed area of Kashmir, a strategically important northwestern border state with a Muslim majority annexed by India, lasted until 1949 and broke out again in 1965–

Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–

The Congress Party leadership pursued nationalist, state-

At independence, Pakistan was divided between eastern and western provinces separated by more than a thousand miles of Indian territory, as well as by language, ethnic background, and social custom. The Bengalis of East Pakistan constituted a majority of Pakistan’s population as a whole, but were neglected by the central government, which remained in the hands of West Pakistan’s elite after Jinnah’s death. In 1971 the Bengalis revolted and won their independence as the new nation of Bangladesh after a violent civil war. Bangladesh, a secular parliamentary democracy, struggled to find political and economic stability amid famines that resulted from monsoon floods, tornadoes, and cyclones in the vast, low-