A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 972

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 984

The Vietnam War

French Indochina experienced the bitterest struggle for independence in Southeast Asia. With financial backing from the United States, France tried to reimpose imperial rule there after the Communist and nationalist guerrilla leader Ho Chi Minh (1890–

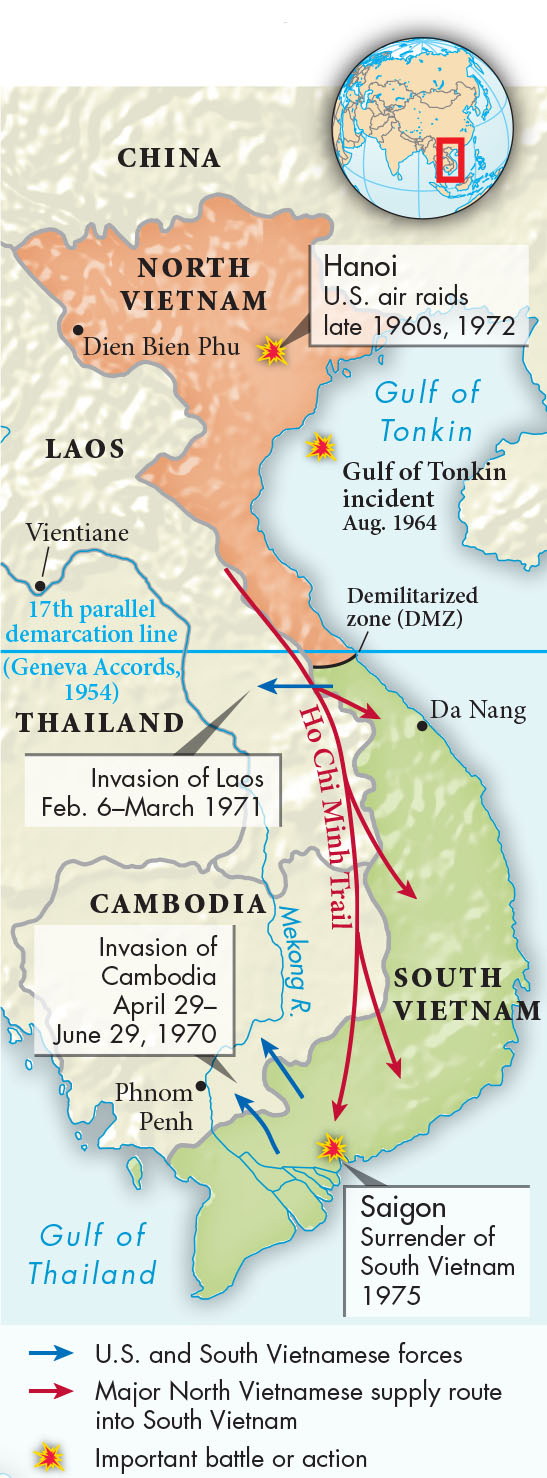

Cold War fears and U.S. commitment to the ideology of containment drove the United States to get involved in Vietnam. The administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower (elected in 1952) refused to sign the Geneva Accords that temporarily divided the country, and provided military aid to help the south resist North Vietnam. Eisenhower’s successor, John F. Kennedy, increased the number of American “military advisers.” In 1964 President Lyndon Johnson greatly expanded America’s role in the Vietnam conflict, declaring, “I am not going to be the President who saw Southeast Asia go the way China went.”9 (See “Viewpoints 31.2: Ho Chi Minh, Lyndon Johnson, and the Vietnam War.”)

The American strategy was to “escalate” the war sufficiently to break the will of the North Vietnamese and their southern allies without resorting to “overkill,” which might risk war with the entire Communist bloc. South Vietnam received massive military aid. Large numbers of American forces joined in combat. The United States bombed North Vietnam with ever-

Most Americans initially saw the war as part of a legitimate defense against communism, but the combined effect of watching the results of the violent conflict on the nightly television news and experiencing the widening dragnet of a military draft spurred a growing antiwar movement on U.S. college campuses. In 1965 student protesters joined forces with old-

Elected in 1968, President Richard Nixon sought to disengage America gradually from Vietnam. He intensified the continuous bombardment of the enemy while simultaneously pursuing peace talks with the North Vietnamese. He also began a slow process of withdrawal from Vietnam in a process called “Vietnamization,” which transferred the burden of the war to the South Vietnamese army. He cut American forces there from 550,000 to 24,000 in four years. Nixon finally reached a peace agreement with North Vietnam in 1973 that allowed the remaining American forces to complete their withdrawal in 1975.

Despite tremendous military effort in the Vietnam War by the United States, the Communists proved victorious in 1975 and created a unified Marxist nation. After more than thirty-