A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 980

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 994

Chapter Chronology

Cuba remained practically an American colony until the 1930s, when a series of rulers with socialist and Communist leanings seized and lost power. Cuba’s political institutions were weak and its politicians corrupt. In March 1952 Fulgencio Batista (1901–1973) staged a coup with American support and instituted a repressive authoritarian regime that favored wealthy Cubans and multinational corporations. Though Cuba was one of Latin America’s most prosperous countries, tremendous differences remained between rich and poor.

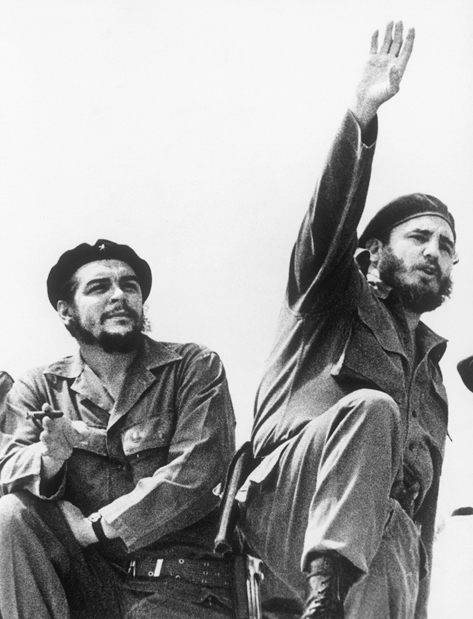

The Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro (b. 1927) began in 1953. Castro’s second-in-command, the legendary Argentine revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928–1967), and a force of guerrilla rebels finally overthrew the Cuban government on New Year’s Day 1959. Castro had promised a revolution that pursued land reform, nationalized industries, and imposed limits on rent to help the urban poor. Affluent Cubans began fleeing to Miami. The U.S. Eisenhower administration slashed Cuban import quotas and began planning to depose Castro. In April 1961 U.S. president John F. Kennedy carried out the plans created by Eisenhower to use Cuban exiles to topple Castro, but when the invasion force landed ashore at the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban revolutionary army, commanded directly by Castro, repelled them in an embarrassment to the United States.

Castro had not come to power as a Communist: his main aim had been to regain control of Cuba’s economy and politics from the United States. But U.S. efforts to overthrow him and to starve the Cuban economy drove him to form an alliance with the Soviet Union, which agreed to place nuclear missiles in Cuba to protect against another U.S. invasion. When Kennedy demanded the missiles be removed, the military and diplomatic brinksmanship of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis ensued. In 1963 the United States placed a complete commercial and diplomatic embargo on Cuba that has remained in place ever since.

Castro now declared himself a Marxist-Leninist and relied on Soviet military and economic support, though Cuba retained a revolutionary ethos that differed from the rest of the Soviet bloc. Castro was committed to spreading revolution to the rest of Latin America, and Guevara participated in revolutionary campaigns in the Congo and Bolivia before being assassinated by U.S.-trained Bolivian forces in 1967. Within Cuba activists swept into the countryside and taught people who were illiterate. Medical attention and education became free and widely accessible. The Cuban Revolution inspired young radicals across Latin America to believe in the possibility of swift revolution and brisk reforms to combat historic inequalities. But these reforms were achieved at great cost and through the suppression of political dissent. Castro declared in 1961, “Inside of the revolution anything, outside the revolution, nothing.”11 Political opponents were jailed or exiled. Meanwhile, reforms were improvised with ideological objectives rather than economic logic, which often resulted in productive inefficiency and scarcity of foodstuffs and other goods.