A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 1000

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 1013

Chapter Chronology

Revolution and War in Iran and Iraq

In oil-rich Iran foreign powers competed for political influence in the decades after the Second World War, and the influence of the United States in particular helped trigger a revolutionary backlash. In 1953 Iran’s prime minister, Muhammad Mossadegh (1882–1967), tried to nationalize the British-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, forcing the pro-Western shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi (r. 1941–1979) to flee to Europe. But Mossadegh’s victory was short-lived. Loyal army officers, with the help of the American CIA, quickly restored the shah to his throne.

Pahlavi set out to build a powerful modern nation to ensure his rule, and Iran’s gigantic oil revenues provided the necessary cash. The shah undermined the power bases of the traditional politicians — large landowners and religious leaders — by means of land reform, secular education, and increased power for the central government. Modernization surged forward, accompanied by widespread corruption and harsh dictatorship. The result was a violent reaction against modernization and secular values: an Islamic revolution in 1979 aimed at infusing strict Islamic principles into all aspects of personal and public life. Led by the Islamic cleric Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini, the fundamentalists deposed the shah and tried to build their vision of a true Islamic state.

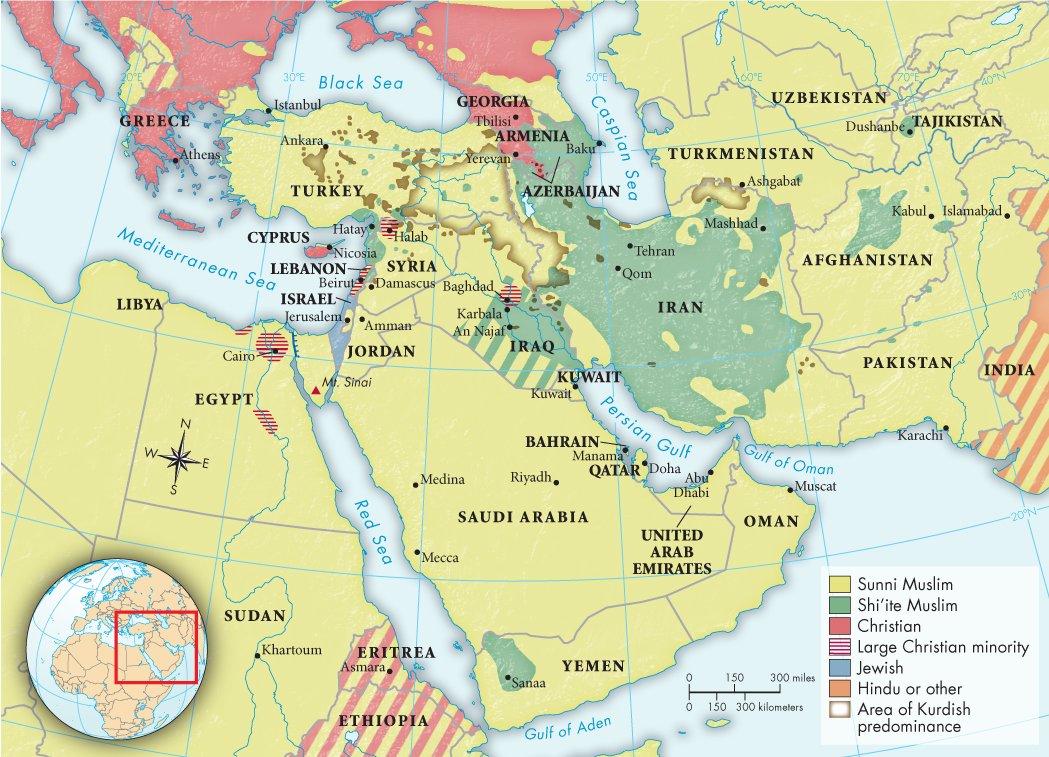

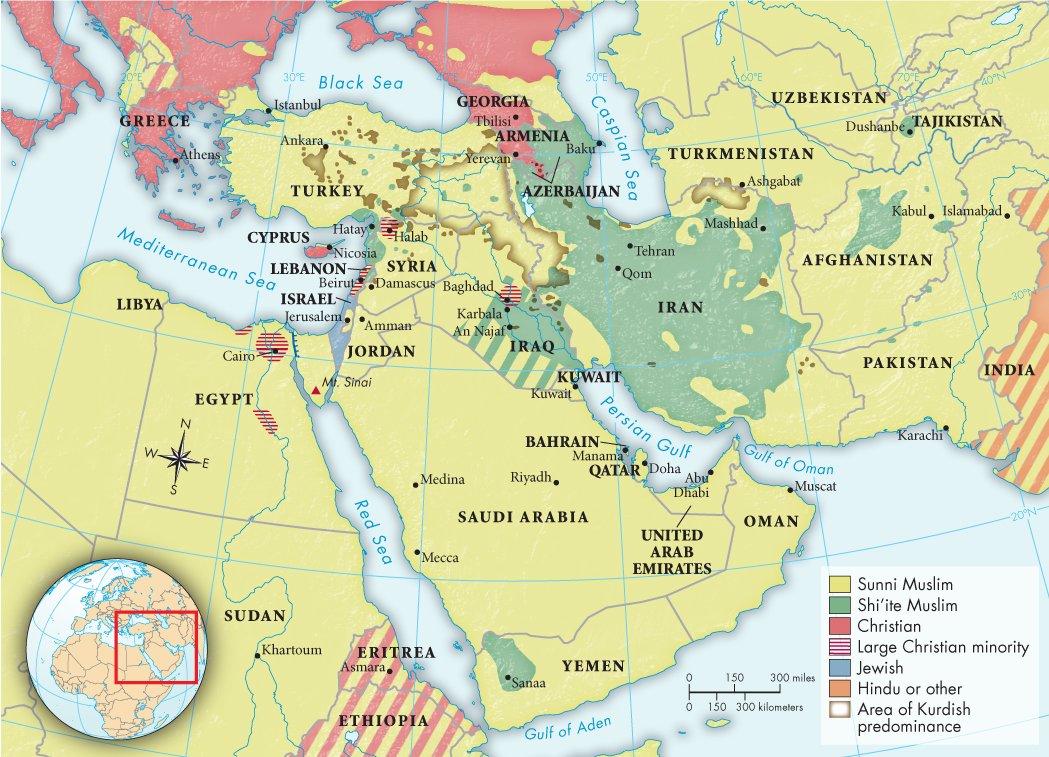

Iran’s revolution frightened its neighbors. Iraq, especially, feared that Iran — a nation of Shi’ite Muslims — would succeed in getting Iraq’s Shi’ite majority to revolt against its Sunni leaders (Map 32.2). In September 1980 Iraq’s ruler, Saddam Hussein (1937–2006), launched a surprise attack against Iran. Hussein emerged from the tradition of Ba’athist secular nationalism within the armed forces. With their enormous oil revenues and powerful armed forces, Iran and Iraq — Persians and Arabs, Islamists and nationalists — clashed in an eight-year conflict that killed hundreds of thousands of soldiers on both sides before ending in a modest victory for Iran in 1988.

Mapping the PastMAP 32.2 Abrahamic Religions in the Middle East and Surrounding Regions Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, which all trace their origins back to the patriarch Abraham, have significant populations in the Middle East. Since the 1979 Iranian revolution, Shi’ites throughout the region have become more vocal in their demands for equality and power. One of the largest stateless ethnic groups, the Kurds, who follow various religions, has become a major player in the politics of the region, especially in Iraq and Turkey, where the group seeks Kurdish independence.ANALYZING THE MAP Which religion dominates? Where are the largest concentrations of Jews and Christians in the Middle East located?CONNECTIONS How have divisions between Shi’ite and Sunni Muslims contributed to war in the region?

Saddled with the costs of war, Hussein eyed Kuwait’s great oil wealth. In August 1990 he ordered his forces to overrun his tiny southern neighbor and proclaimed its annexation to Iraq. To Hussein’s surprise, his troops were driven out of Kuwait by an American-led, United Nations–sanctioned military coalition, which included Arab forces from Egypt, Syria, and Saudi Arabia. The United Nations Security Council imposed economic sanctions on Iraq as soon as it invaded Kuwait, and these sanctions continued after the Persian Gulf War to force Iraq to destroy its stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons. Through the agreement that ended the war in 1991, United Nations inspectors supervised the destruction of many such weapons. The United States charged Iraq with deceiving UN inspectors and engaging in ongoing weapons development. An American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 began the Second Persian Gulf War and overthrew Saddam Hussein’s regime. The invasion led to a lengthy U.S. occupation and a violent insurgency against U.S. military forces, which remained in Iraq until 2011.

As secular Iraq staggered, the Iran revolutionary regime seemed to moderate. Following the constitution established by Ayatollah Khomeini, executive power in Iran was divided between a Supreme Leader and twelve-member Guardian Council selected by high Islamic clerics, and a popularly elected president and parliament. A reform movement pressed for relaxation of strict Islamic decrees and elected a moderate, Muhammad Khatami (b. 1943), as president in 1997 and again in 2001. The Supreme Leader, controlling the army and the courts, vetoed Khatami’s reforms and jailed some of the religious leadership’s most vocal opponents.

In 2005 dubious election returns gave the presidency to conservative populist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (b. 1956). He engaged in brinksmanship over the development of a nuclear weapons program, called for Israel’s destruction, and backed the Hamas Party in the Gaza Strip and Hezbollah in Lebanon. Ahmadinejad won re-election in 2009 after a bitterly contested challenge from moderates. The government suppressed a “green revolution” of protests that broke out after news of the election results, proving itself more able to stifle public unrest than were the leaders unseated by the Arab Spring. In 2013 opposition groups came together to support the election of Hassan Rouhani, a centrist cleric who promised civil rights reforms and has made overtures to the West in the hopes of relieving economic sanctions in return for negotiating an end to Iran’s nuclear weapons program.