A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 1001

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 1015

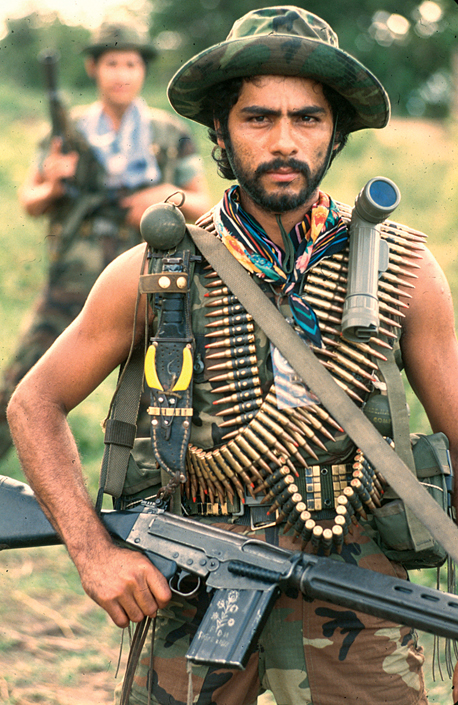

Civil Wars in Central America

Central America experienced the greatest violence in Latin America during the Cold War. Many Latin American governments had long supported the interests of U.S. companies like United Fruit, which grew export crops and relied on cheap labor. In the second half of the twentieth century nationalists in Central America sought economic development that was less dependent on the United States and U.S. corporations, and groups of peasants and urban workers began to press for political rights and improved living standards. Through the lens of the Cold War, Central American conservatives and the United States government saw these nationalists, peasants, and workers as Communists who should be suppressed. In turn, many workers and peasants radicalized and formed Marxist revolutionary movements. The result of this conflict, and of U.S. support for right-

In Guatemala reformist president Jacobo Arbenz was deposed in a military coup organized by the CIA in 1954. Subsequent Guatemalan leaders backed by the U.S. government violently suppressed peasant movements, resulting in the likely death of over two hundred thousand mostly indigenous people. In 2013 former dictator José Efraín Ríos-

El Salvador and Nicaragua, too, faced civil wars. In 1979 the Sandinista movement overthrew dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle. The Sandinistas, who conducted a revolutionary transformation of Nicaragua inspired by Communist rule in Cuba, were undermined by war with a U.S.-trained and U.S.-financed insurgent army called the Contras. In El Salvador a right-

U.S. policies that encouraged one faction to fight against the other deepened political instability and repression and intensified these civil wars. Acting against U.S. wishes, in 1986 Costa Rican president Oscar Arias mediated peace talks among the warring factions in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala, which ended the wars and initiated open elections in each country, with former armed rivals competing instead at the ballot box. Peace did not bring prosperity, and in the decades following the end of the civil wars both poverty and violence have remained intense, prompting many Central Americans to seek opportunity in Mexico and the United States.