A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 1018

Listening to the Past

A Solidarity Leader Speaks from Prison

Listening to the Past

A Solidarity Leader Speaks from Prison

The powerful Solidarity movement in Poland built a broad-

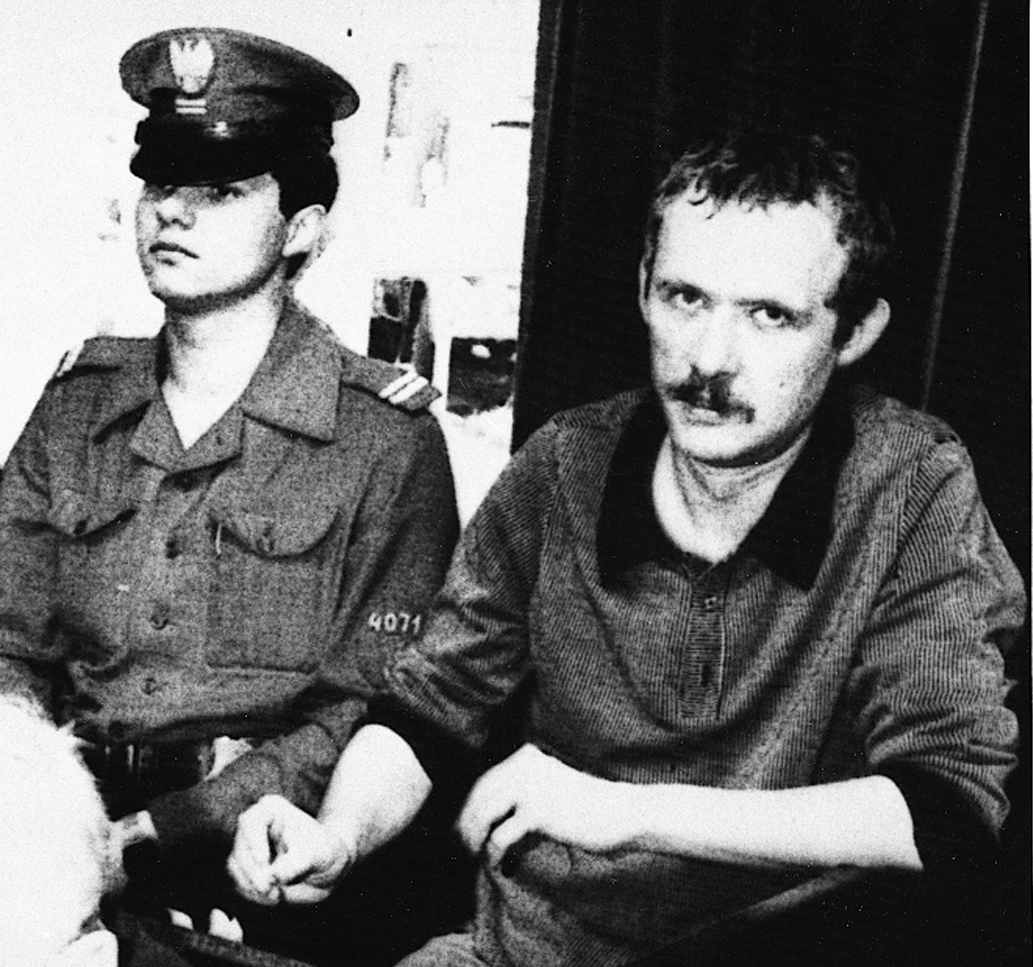

Adam Michnik was one of Wałęsa’s closest coworkers. Whereas Wałęsa was a skilled electrician and a devout Catholic, Michnik was an intellectual and a disillusioned Communist. Their faith in nonviolence and in gradual change united them. Trained as a historian but banned from teaching because of his leadership in student strikes in 1968, Michnik worked in a factory. In 1977 he helped found the Committee for the Defense of Workers (KOR), which supported workers fired for striking. In December 1981 Michnik was arrested with the rest of Solidarity’s leadership. While in prison, he wrote his influential Letters from Prison, from which this excerpt is taken.

“Why did Solidarity renounce violence? This question returned time and again in my conversations with foreign observers. I would like to answer it now. People who claim that the use of force in the struggle for freedom is necessary must first prove that in a given situation it will be effective and that force, when it is used, will not transform the idea of liberty into its opposite.

No one in Poland is able to prove today that violence will help us to dislodge Soviet troops from Poland and to remove the communists from power. The U.S.S.R. has such enormous military power that confrontation is simply unthinkable. In other words, we have no guns. Napoleon, upon hearing a similar reply, gave up asking further questions. However, Napoleon was above all interested in military victories and not building democratic, pluralistic societies. We, by contrast, cannot leave it at that.

In our reasoning, pragmatism is inseparably intertwined with idealism. Taught by history, we suspect that by using force to storm the existing Bastilles we shall unwittingly build new ones. It is true that social change is almost always accompanied by force. But it is not true that social change is merely a result of the violent collision of various forces. Above all, social changes follow from a confrontation of different moralities and visions of social order. Before the violence of rulers clashes with the violence of their subjects, values and systems of ethics clash inside human minds. . . .

Solidarity has never had a vision of an ideal society. It wants to live and let live. Its ideals are closer to the American Revolution than to the French. . . . The ethics of Solidarity, with its consistent rejection of the use of force, has a lot in common with the idea of nonviolence as espoused by Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. But it is not an ethic representative of pacifist movements.

Pacifism as a mass movement aims to avoid suffering; pacifists often say that no cause is worth suffering or dying for. The ethics of Solidarity are based on an opposite premise: that there are causes worth suffering and dying for. Gandhi and King died for the same cause as the miners in Wujek who rejected the belief that it is better to remain a willing slave than to become a victim of murder [and who were shot down by police for striking against the imposition of martial law in 1981]. . . .

But ethics cannot substitute for a political program. We must therefore think about the future of Polish-

The Soviet state has a new leader; he is a symbol of transition from one generation to the next within the Soviet elite. This change may offer an opportunity, since Mikhail Gorbachev has not yet become a prisoner of his own decisions. No one can rule out the possibility that an impulse for reform will spring from the top of the hierarchy of power. This is exactly what happened in the time of Alexander II and, a hundred years later, under Khrushchev. Reform is always possible, even in the face of resistance by the old apparatus.”

Source: Adam Michnik, Letters from Prison and Other Essays, trans. Maya Latynski (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1985), pp. 86–

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- Do you find Michnik’s arguments for opposing the government with nonviolent actions convincing? Why or why not?

- How did Michnik’s study of history influence his thinking? What lessons did he learn?