A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 996

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 1009

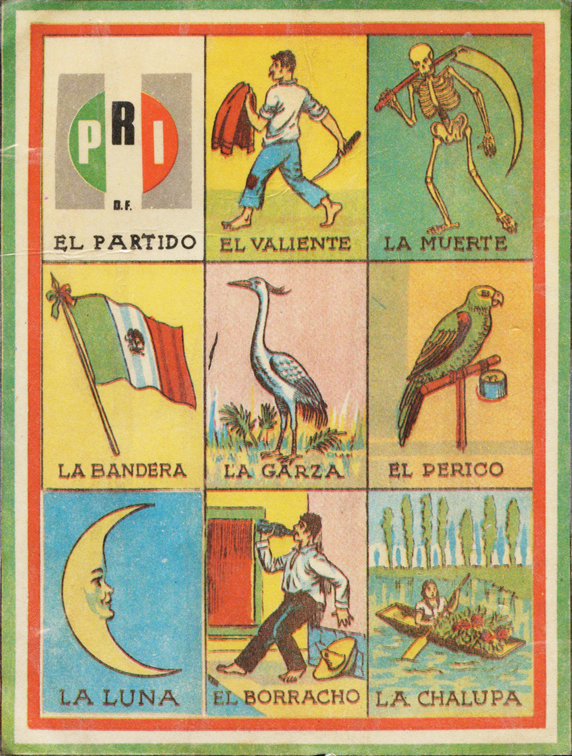

Mexico Under the PRI

By the 1960s Mexico was a democracy that functioned like a dictatorship. The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) held absolute power to a degree rivaled only by the Communist parties of countries like China and the Soviet Union. PRI candidates held nearly every public office. The PRI controlled both labor unions and federations of businessmen. More than a party, it was a vast system of patronage. Even at the landfills where the most desperately poor scavenged through trash, a PRI official with a beach chair and umbrella sat watch and collected a cut of their meager earnings. Mexico’s road from the nationalist economic project that emerged from the 1910 revolution to the liberal reforms of the 1960s and 1970s is also the story of the PRI.

The PRI claimed the legacy of the Mexican Revolution: it was the party of land reform, universal public education, industrialization, and state ownership of the country’s oil reserves. But these claims were undermined when PRI politicians ordered the deadly crackdown on student protesters in 1968 (see “The World in 1968” in Chapter 31). The party that had defined itself as the agent of progress and change became the reactionary party preserving a corrupt order.

In 1970 the PRI chose and elected as president populist Luis Echeverría, who sought to reclaim the mantle of reform by nationalizing utilities and increasing social spending. Echeverría and his successor, José López Portillo, embarked on massive development projects financed through projected future earnings of the state oil monopoly PEMEX. Amid inflation, corruption, and the decline of oil prices and demand during the global recession of the 1980s, the Mexican government stopped payments on its foreign debt, nationalized the banks, and steeply devalued the peso. As Mexico fell into the debt crisis, it was compelled to embrace the Washington Consensus, which meant restricted spending, opening trade borders, and privatization.

Several dramatic events discredited the PRI, beginning with the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre and followed by the debt crisis and the painful liberal reforms. The PRI was further undermined by its inept and corrupt response to a devastating earthquake that struck Mexico City in 1986. Two years later the PRI faced its first real presidential election challenge. Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, who was the son of populist Lázaro Cárdenas and was named after the last Aztec ruler, ran against PRI candidate Carlos Salinas de Gortari. On election night, as the vote counting favored Cárdenas, the government declared that the computers tabulating the votes had crashed and declared Gortari the winner. The PRI-

The debt crisis forced the PRI government to abandon the nationalist development project created in the decades after the 1910 revolution and to embrace economic liberalism, but the experience with neoliberalism proved equally corrupt. Mexico continued to face economic crises such as a 1994 financial panic. As the PRI’s power slipped and as Mexico’s trade with the United States intensified, violent drug cartels proliferated, especially in Mexico’s northern border states, and competed for the lucrative drug trade into the United States.