A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 1032

Chapter Chronology

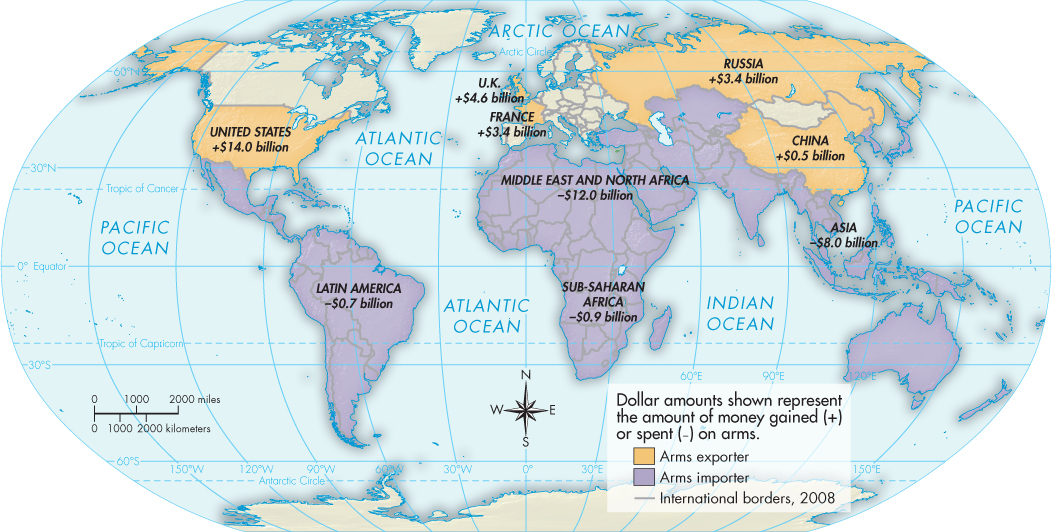

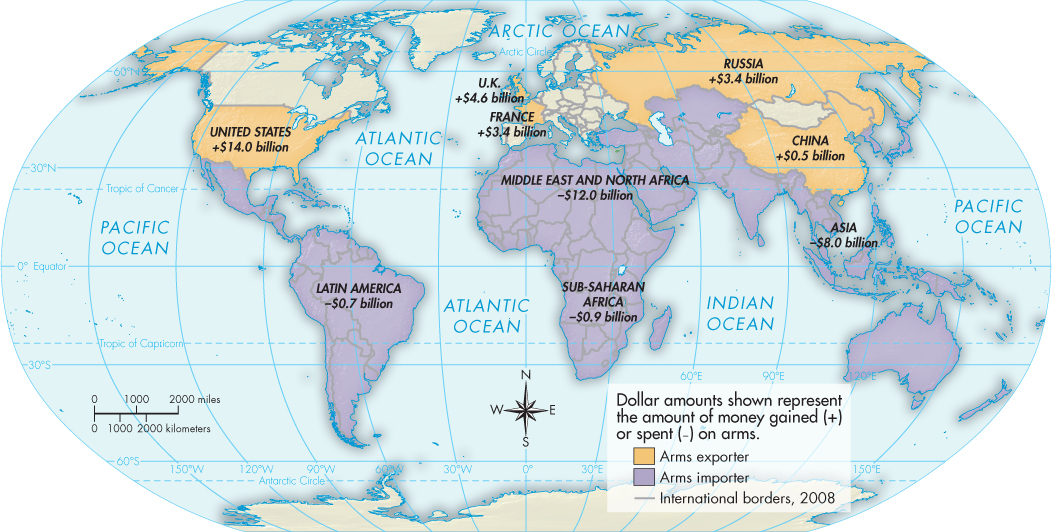

Global Trade

Arms, with unprecedented destructive powers, command billions of dollars annually on the open global marketplace. On April 16, 1953, U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower spoke about the tremendous sums the Soviet Union and the United States were spending on Cold War weapons:

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. The world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. . . . This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense.

In the approximately sixty years since Eisenhower’s speech, the spending has never stopped, not even after the Cold War’s end. In 2009 global military spending exceeded $1.53 trillion; the United States accounted for nearly half of that total. Globally, in 2009 the value of all conventional arms transfer agreements to developing nations was more than $45.1 billion, and deliveries totaled $17 billion. Although those numbers have been dropping since the early 1990s, global arms manufacturing and trade remains big business.

Three different categories of arms are available on the world market. The category that generally receives the most attention is nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. After the Soviet Union collapsed, there was widespread fear that former Soviet scientists would sell nuclear technology, toxic chemicals, or harmful biological agents from old, poorly guarded Soviet labs and stockpiles to the highest bidders. Recognizing the horrific danger such weapons represent, the world’s nations have passed numerous treaties and agreements limiting their production, use, and stockpiling. The most important of these are the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (1970), the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (1972), and the Chemical Weapons Convention (1993).

MAP 33.1 The Arms Trade Source: Map and data from www.controlarms.org/the_issues/movers_shakers.htm, adapted with the permission of Oxfam GB, Oxfam House, John Smith Drive, Cowley, Oxford OX4 2JY, UK, www.oxfam.org.uk. Oxfam GB does not necessarily endorse any text or activities that accompany the materials, nor has it approved the adapted text.

A second category of arms is so-called heavy conventional weapons, such as tanks, heavy artillery, jet planes, missiles, and warships. In general, worldwide demand for these weapons declined significantly after the Cold War ended. Only a few companies located in the largest industrialized nations have the scientists, the funding, and the capacity to produce them. Because the major Soviet- and Western-bloc nations had large weapon surpluses in 1991, most of the new weapons produced in this category have been made for export. In 1995 the United States for the first time produced more combat aircraft for export sales than for U.S. military use. New demand comes mainly from developing nations that are not technologically or financially capable of producing such weapons, such as Pakistan, which received fourteen F-16s in summer 2010 and has announced plans to purchase more. New or potential NATO member states have been another significant market for the United States, Great Britain, France, and Germany. In 2003, for example, the United States sold forty-eight F-16 fighter aircraft worth $3.5 billion to Poland, while Germany received $1 billion from Greece for 170 battle tanks. Many of the former Soviet-bloc countries of eastern Europe have illegally served as points of origin or transfer points for sales to embargoed nations such as North Korea and to terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda.

The third category is small arms and light conventional weapons (SALWs). These are almost any remotely portable weapons, including automatic rifles, machine guns, pistols, antitank weapons, small howitzers and mortars, Stinger missiles and other shoulder-fired weapons, grenades, plastic explosives, land mines, machetes, small bombs, and ammunition. SALWs make up the majority of weapons exchanged in the global arms trade. They also do the most harm. Every year, they are responsible for over a half million deaths.

SALWs are popular because they have relatively long lives and are low-maintenance, cheap, easily available, highly portable, and easily concealable. Many can be used by child soldiers. Globally, there are around 650 million guns, about 60 percent of them owned by private citizens. Fifteen billion to twenty billion or more rounds of ammunition are produced annually. Despite widespread concern about terrorists obtaining nuclear or chemical weapons, terrorists on the whole favor small conventional weapons such as truck and car bombs and automatic rifles and pistols. One of the most deadly SALWs is the land mine. Over 110 million of them still lie buried in Afghanistan, Angola, Iran, and other former war zones, and they continue to kill or injure fifteen thousand to twenty thousand people a year.

Over ninety countries manufacture and sell SALWs, but the five permanent members of the UN Security Council — France, Britain, the United States, China, and Russia — dominate. The United States and Britain account for nearly two-thirds of all conventional arms deliveries, and these two nations plus France sometimes earn more income from arms sales to developing countries than they provide in aid. The total legal international trade in SALWs is estimated at about $8 billion a year; the illegal total is about $1 billion. Of course, every legal weapon can easily become an illegal one.

In 2000 UN secretary-general Kofi Annan observed that “the death toll from small arms dwarfs that of all other weapons systems — and in most years greatly exceeds the toll of the atomic bombs that devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In terms of the carnage they cause, small arms, indeed, could well be described as ‘weapons of mass destruction.’”*