A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 194

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 190

Tang Culture

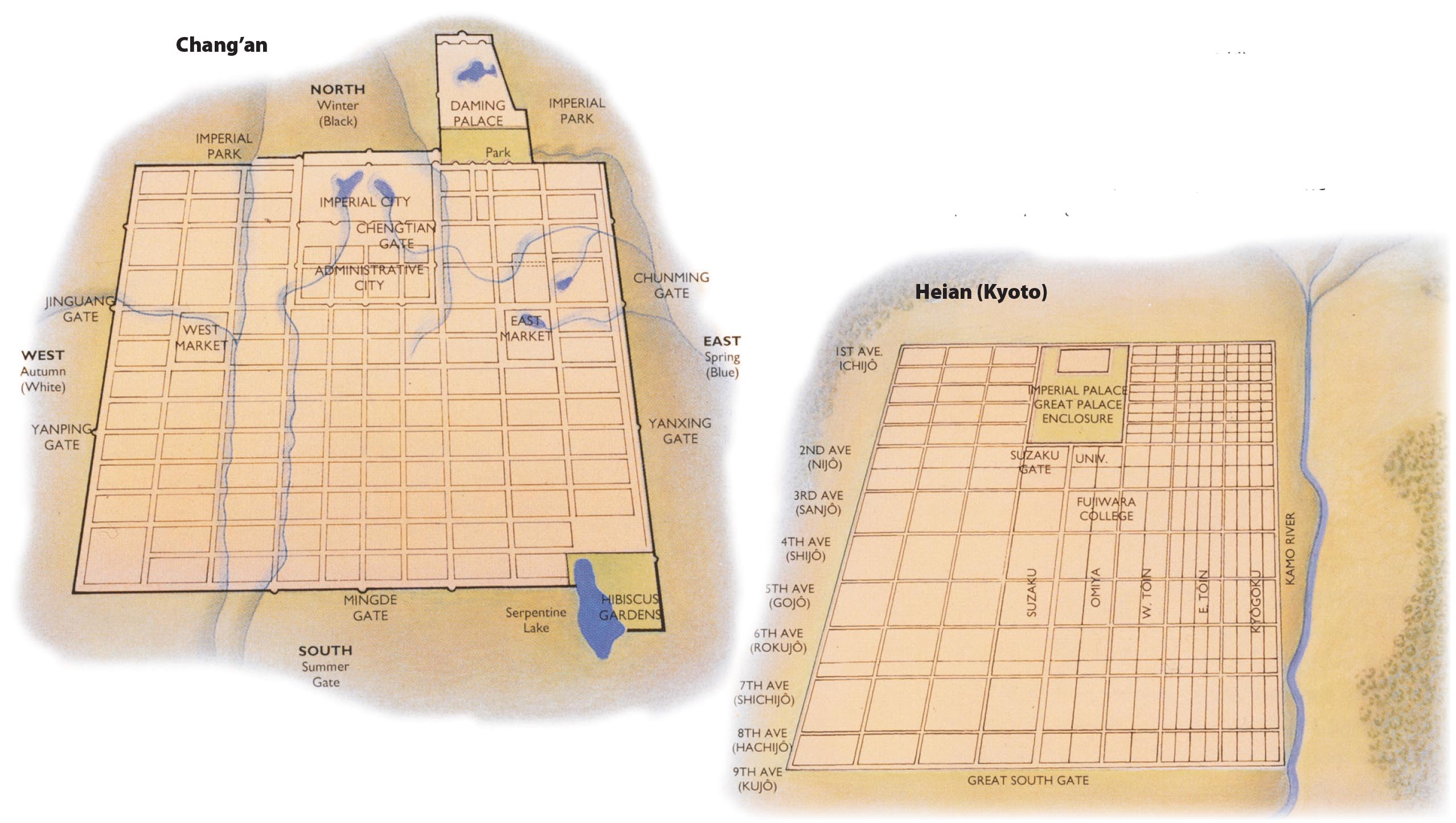

The reunification of north and south led to cultural flowering. The Tang capital cities of Chang’an and Luoyang became great metropolises; Chang’an and its suburbs grew to more than 2 million inhabitants (probably making it the largest city in the world at the time). The cities were laid out in rectangular grids and contained a hundred-

In these cosmopolitan cities, knowledge of the outside world was stimulated by the presence of envoys, merchants, pilgrims, and students who came from neighboring states in Central Asia, Japan, Korea, Tibet, and Southeast Asia. Because of the presence of foreign merchants, many religions were practiced, including Nestorian Christianity, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and Islam, although none of them spread into the Chinese population the way Buddhism had a few centuries earlier. Foreign fashions in hair and clothing were often copied, and foreign amusements such as the Persian game of polo found followings among the well-

The Tang Dynasty was the great age of Chinese poetry. Skill in composing poetry was tested in the civil service examinations, and educated men had to be able to compose poems at social gatherings. The pain of parting, the joys of nature, and the pleasures of wine and friendship were all common poetic topics. One of Li Bo’s (701–

A cup of wine, under the flowering trees;

I drink alone, for no friend is near.

Raising my cup I beckon the bright moon,

For he, with my shadow, will make three men.

The moon, alas, is no drinker of wine;

Listless, my shadow creeps about at my side.

. . .

Now we are drunk, each goes his way.

May we long share our odd, inanimate feast,

And we meet at last on the cloudy River of the sky.6

The poet Bo Juyi (772–

From these high walls I look at the town below

Where the natives of Pa cluster like a swarm of flies.

How can I govern these people and lead them aright?

I cannot even understand what they say.

But at least I am glad, now that the taxes are in,

To learn that in my province there is no discontent.7

In Tang times Buddhism fully penetrated Chinese daily life. Stories of Buddhist origin became widely known, and Buddhist festivals, such as the festival for feeding hungry ghosts in the summer, became among the most popular holidays. Buddhist monasteries became an important part of everyday life. They ran schools for children. In remote areas they provided lodging for travelers. Merchants entrusted their money and wares to monasteries for safekeeping, in effect transforming the monasteries into banks and warehouses. The wealthy often donated money or land to support temples and monasteries, making monasteries among the largest landlords.

At the intellectual and religious level, Buddhism was developing in distinctly Chinese directions. Two schools that thrived were Pure Land and Chan. Pure Land appealed to laypeople because its simple act of calling on the Buddha Amitabha and his chief helper, the compassionate bodhisattva Guanyin, could lead to rebirth in Amitabha’s paradise, the Pure Land. Among the educated elite the Chan school (known in Japan as Zen) also gained popularity. Chan teachings rejected the authority of the sutras and claimed the superiority of mind-

Opposition to Buddhism re-