A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 186

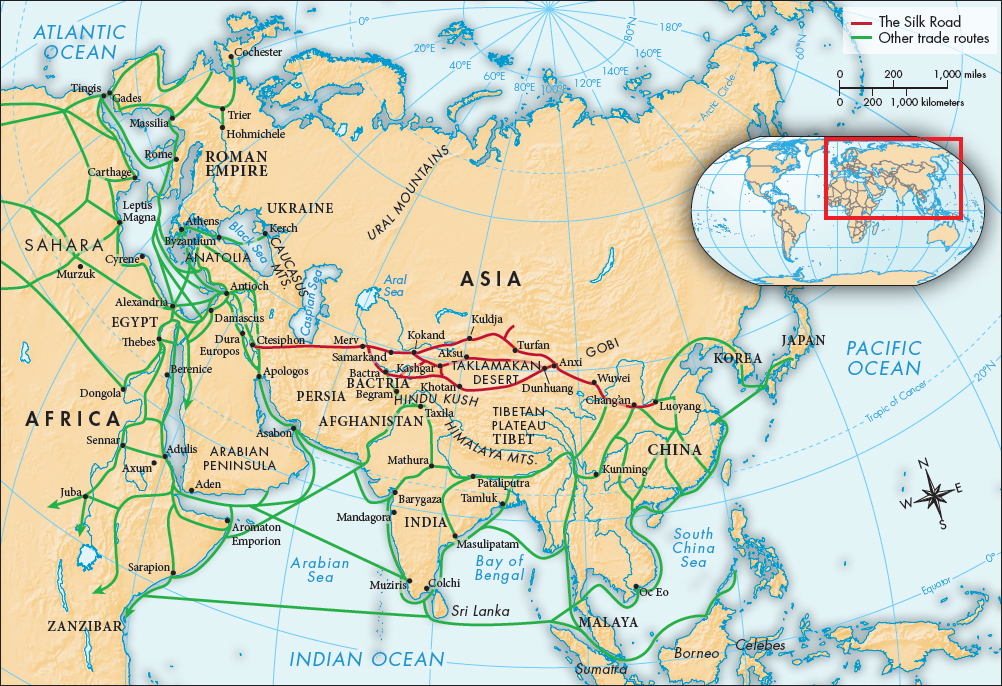

Global Trade

Silkwas one of the earliest commodities to stimulate international trade. By 2500 B.C.E. Chinese farmers had domesticated Bombyx mori, the Chinese silkworm, and by 1000 B.C.E. they were making fine fabrics with complex designs. Sericulture (silkmaking) is labor-

What made silk the most valued of all textiles was its beauty and versatility. It could be made into sheer gauzes, shiny satins, multicolored brocades, and plush velvets. Fine Han silks have been found in Xiongnu tombs in northern Mongolia. Korea and Japan not only imported silk but also began silk production themselves, and silk came to be used in both places in much the way it was used in China — for the clothes of the elite, for temple banners, and as a surface for writing and painting. Central Asia, Persia, India, and Southeast Asia also became producers of silk in distinctive local styles. Lacking suitable climates to produce silk, Mongolia and Tibet remained major importers of Chinese silks into modern times.

What makes the silk trade famous, however, is not the trade within Asia but the trade across Asia to Europe. In Roman times silk carried by caravans across Asia or by ships across the Indian Ocean became a high-

In medieval times most of the silk imported into Europe came from Persia, the Byzantine Empire, or the Arab world. Venetian merchants handled much of the trade. Some of this fabric still survives in ancient churches, where it was used for vestments and altar clothes and to wrap relics. In the eleventh century Roger I, king of Sicily, captured groups of silk-

When the Venetian merchant Marco Polo traveled across Asia in the late thirteenth century, he found local silk for sale in Baghdad, Georgia, Persia, and elsewhere, but China remained the largest producer. He claimed that more than a thousand cartloads of silk were brought into the capital of China every day.

With the development of the sea route between western Europe and China from the sixteenth century on, Europe began importing large quantities of Chinese silk, much of it as silk floss — raw silk — to supply Italian, French, and English silk weavers. In 1750 almost 77.2 tons of raw silk and nearly 20,000 bolts of silk cloth were carried from China to Europe. By this period the aristocracy of Europe regularly wore silk clothes, including silk stockings.

Mechanization of silkmaking began in Europe in the seventeenth century. The Italians developed machines to “throw” the silk — doubling and twisting raw silk into threads suitable for weaving. In the early nineteenth century the introduction of Jacquard looms using punched cards made complex patterns easier to weave.

In the 1920s the silk industry was hit hard by the introduction of synthetic fibers, especially rayon and nylon. In the 1940s women in the United States and Europe switched from silk stockings to the much less expensive nylon stockings. European production of silk almost entirely collapsed. After China re-