A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 220

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 219

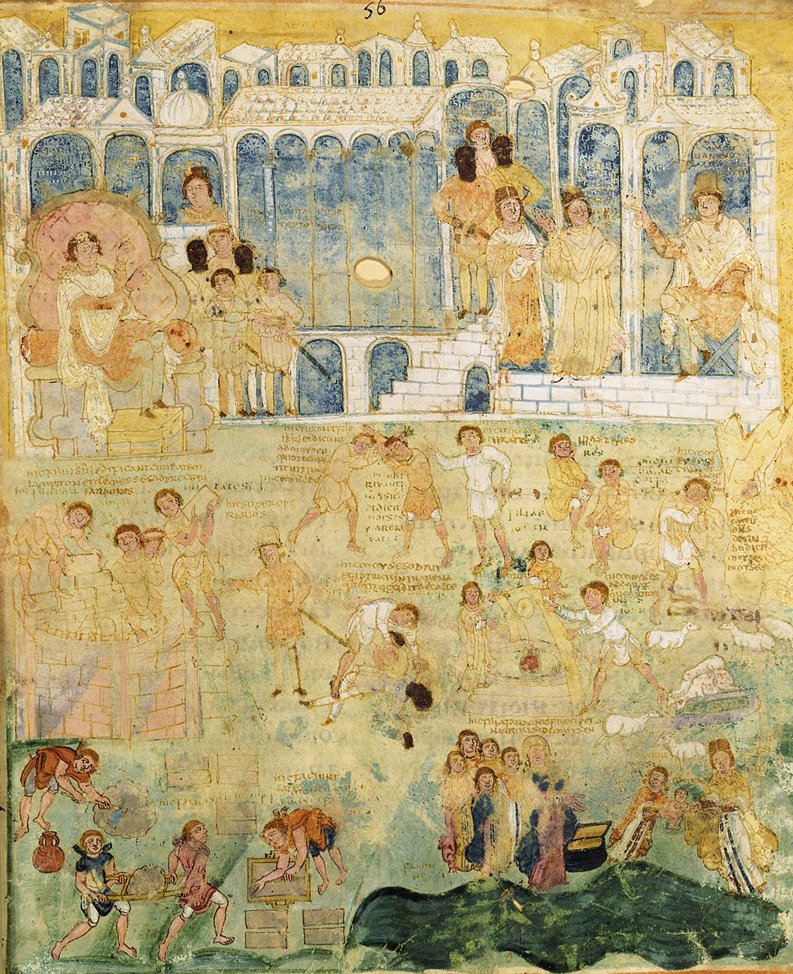

Tribes, Warriors, and Laws

The basic social and political unit among barbarian groups was the tribe or confederation, made up of kin groups whose members believed they were all descended from a common ancestor. Tribes were led by chieftains, recognized by tribe members as the strongest and bravest in battle. Each chief was elected from among the male members of the most powerful family. He led the tribe in war, settled disputes among its members, conducted negotiations with outside powers, and offered sacrifices to the gods. As barbarian groups migrated into and conquered parts of the Western Roman Empire, their chiefs became even more powerful. Often chiefs adopted the title of king, though this title implies broader power than they actually had.

Closely associated with the chief in some tribes was the comitatus (kuhm-

Early barbarian tribes had no written laws. Law was custom, but certain individuals were often given special training in remembering and retelling laws from generation to generation. Beginning in the late fifth century, however, some chieftains began to collect, write, and publish lists of their customs and laws.

Barbarian law codes often included clauses designed to reduce interpersonal violence. Any crime that involved a personal injury, such as assault, rape, and murder, was given a particular monetary value, called the wergeld (WEHR-

The wergeld varied according to the severity of the crime and also the social status and gender of the victim, as shown in these clauses from the law code of the Salian Franks, one of the barbarian tribes.

If any person strike another on the head so that the brain appears, and the three bones which lie above the brain shall project, he shall be sentenced to 1200 denars, which make 300 shillings. . . .

If any one have killed a free woman after she has begun bearing children, he shall be sentenced to 2400 denars, which make 600 shillings.3

In other codes as well, a crime against a woman of childbearing years often carried a wergeld as substantial as that for a man of higher stature, suggesting that barbarians were concerned about maintaining their population levels.

Like most people of the ancient world, barbarians worshipped hundreds of gods and goddesses with specialized functions. They regarded certain natural features as sacred because these were linked to deities. Rituals to honor the gods were held outdoors rather than in temples or churches, often at certain points in the yearly agricultural cycle. Among the Celts, religious leaders called druids had legal and educational as well as religious functions, orally passing down laws and traditions from generation to generation. Bards singing poems and ballads also passed down myths and stories of heroes and gods, which were written down much later.