A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 224

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 222

Chapter Chronology

Missionaries’ Actions

Throughout barbarian Europe, religion was not a private or individual matter; it was a social affair, and the religion of the chieftain or king determined the religion of the people. Thus missionaries concentrated their initial efforts not on ordinary people but on kings or tribal chieftains and the members of their families, who then ordered their subjects to convert. Because they had more opportunity to spend time with missionaries, queens and other female members of the royal family were often the first converts in an area, and they influenced their husbands and brothers. Germanic kings sometimes accepted Christianity because they came to believe that the Christian God was more powerful than pagan gods and that the Christian God — in either its Arian or Roman version — would deliver victory in battle. They also appreciated that Christianity taught obedience to kingly as well as divine authority. Christian missionaries were generally literate, and they taught reading and writing to young men who became priests or officials in the royal household, a service that kings appreciated.

Many barbarian groups were converted by Arian missionaries, who also founded dioceses. Bishop Ulfilas (ca. 310–383), for example, an Ostrogoth himself, translated the Bible from Greek into the Gothic language even before Jerome wrote the Latin Vulgate, creating a new Gothic script in order to write it down. Over the next several centuries this text was recopied many times and carried with the Gothic tribes as they migrated throughout southern Europe. In the sixth and seventh centuries most Goths and other Germanic tribes converted to Roman Christianity, sometimes peacefully and sometimes as a result of conquest. Ulfilas’s Bible — and the Gothic script he invented — were forgotten and rediscovered only a thousand years later.

Tradition identifies the conversion of Ireland with Saint Patrick (ca. 385–461). After a vision urged him to Christianize Ireland, Patrick studied in Gaul and in 432 was consecrated a bishop. He then returned to Ireland, where he converted the Irish tribe by tribe, first baptizing the king.

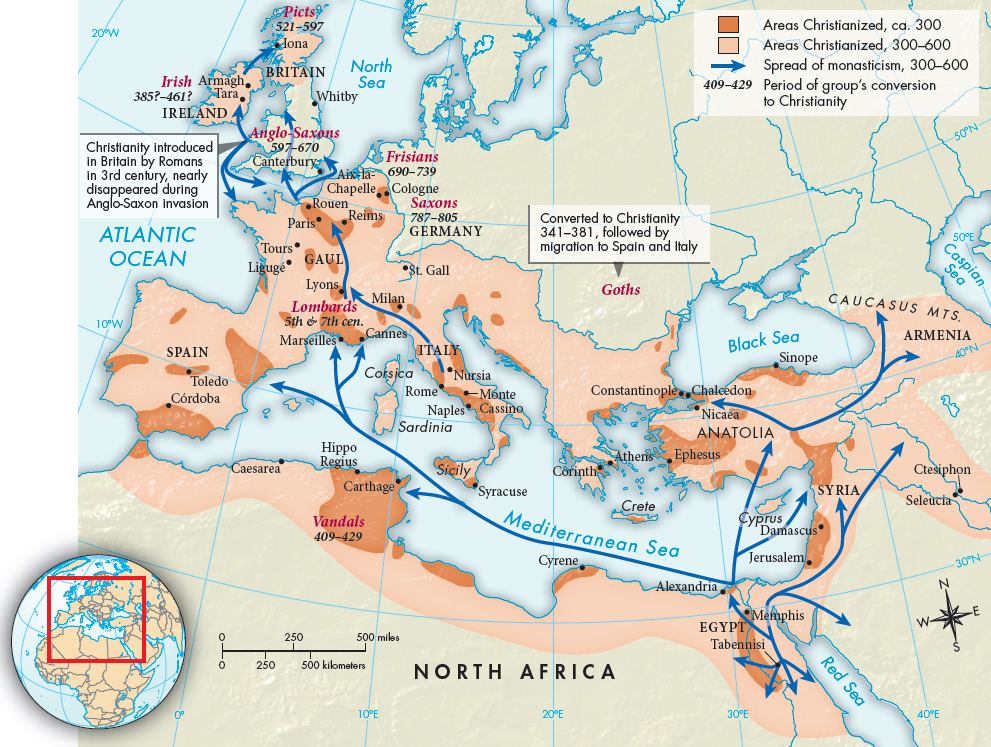

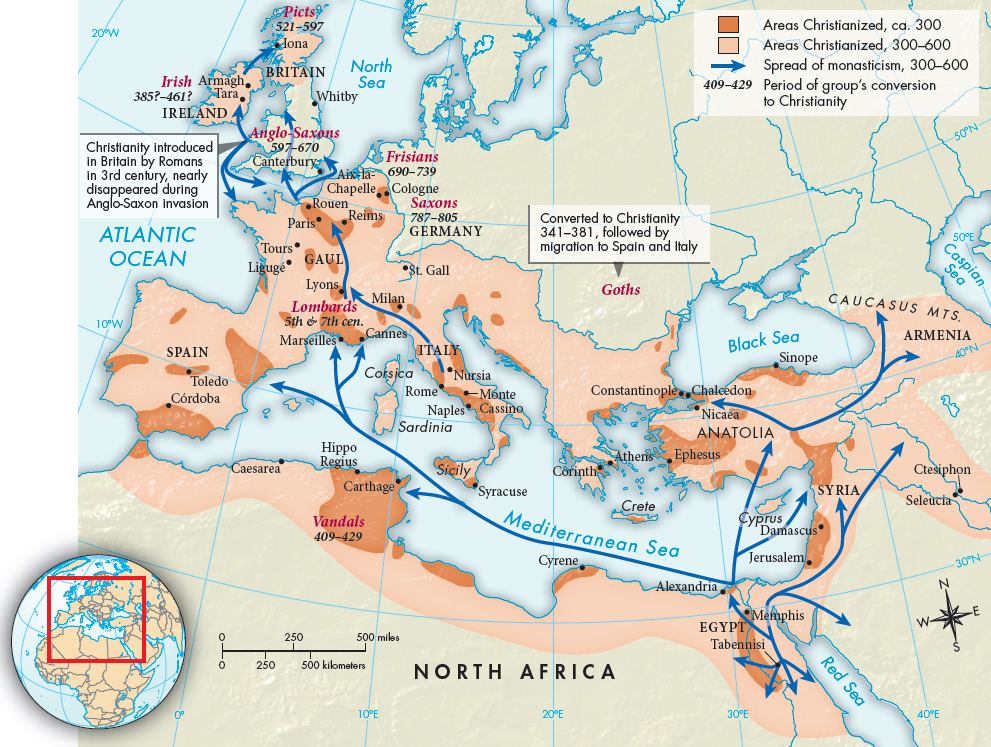

The Christianization of the English began in earnest in 597, when Pope Gregory I (pontificate 590–604) sent a delegation of monks to England. The conversion of the English had far-reaching consequences because Britain later served as a base for the Christianization of Germany and other parts of northern Europe (Map 8.3). Between the fifth and tenth centuries the majority of people living on the European continent and the nearby islands accepted the Christian religion — that is, they received baptism, though baptism in itself did not automatically transform people into Christians.

Mapping the PastMAP 8.3 The Spread of Christianity, ca. 300–800 Originating in the area near Jerusalem, Christianity spread throughout and then beyond the Roman world.ANALYZING THE MAP Based on the map, how did the roads and sea-lanes of the Roman Empire influence the spread of Christianity?CONNECTIONS How does the map support the conclusion that Christianity began as an urban religion and then spread into more rural areas?

In eastern Europe missionaries traveled far beyond the boundaries of the Byzantine Empire. In 863 the emperor Michael III (r. 842–867) sent the brothers Cyril (826–869) and Methodius (815–885) to preach Christianity in Moravia (an eastern region of the modern Czech Republic). Cyril invented a Slavic alphabet using Greek characters, later called the Cyrillic alphabet in his honor. In the tenth century other missionaries spread Christianity, the Cyrillic alphabet, and Byzantine art and architecture to Russia. The Byzantines were so successful that the Russians would later claim to be the successors of the Byzantine Empire.