Understanding World Societies:

Printed Page 410

The Great Famine and the Black Death

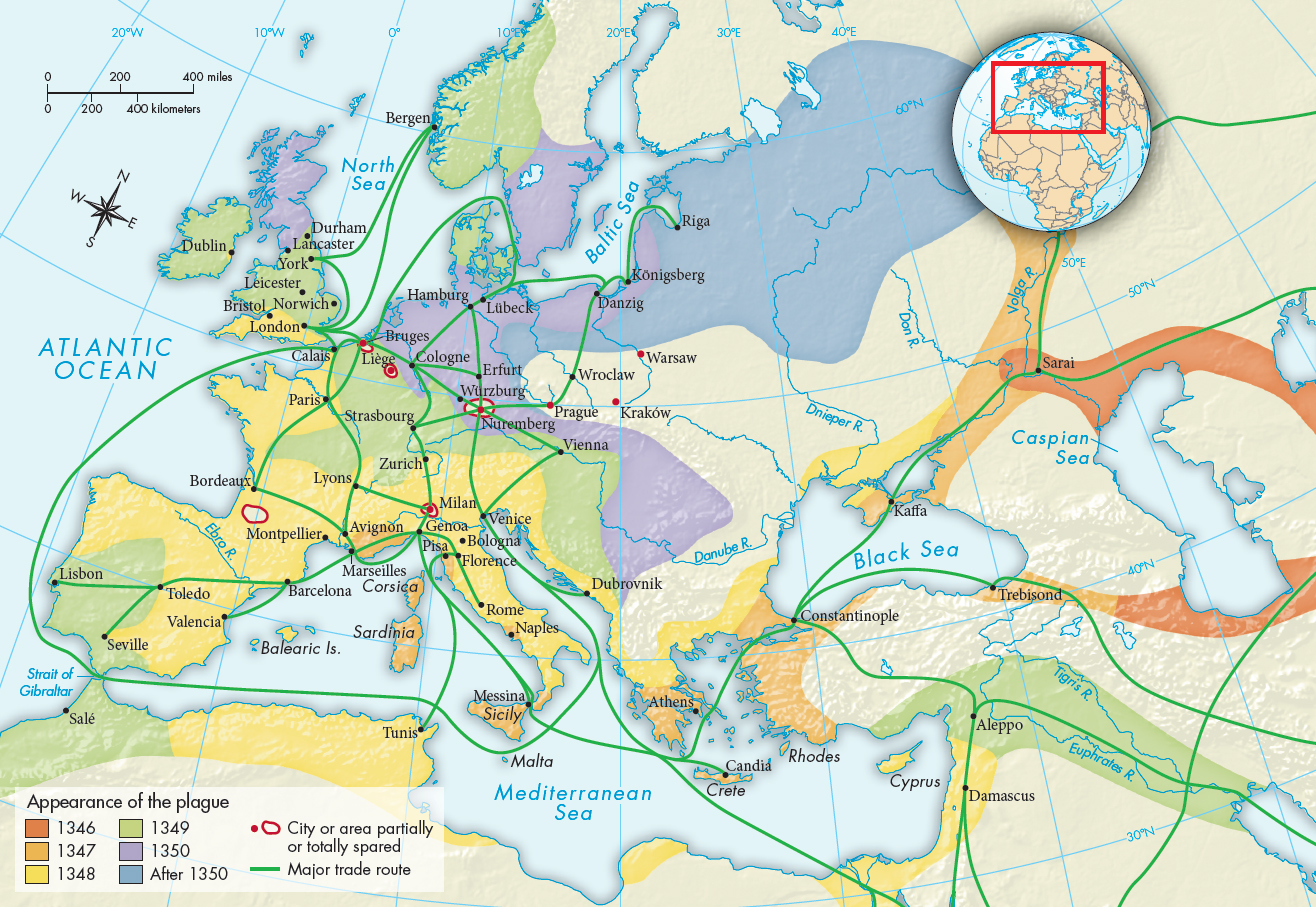

In the first half of the fourteenth century Europe experienced a series of climate changes, especially the beginning of a period of colder and wetter weather that historical geographers label the “little ice age.” Its effects were dramatic and disastrous. Population had steadily increased in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, but with colder weather, poor harvests led to scarcity and starvation. The costs of grain, livestock, and dairy products rose sharply. Almost all of northern Europe suffered a terrible famine between 1315 and 1322, with dire social consequences: peasants were forced to sell or mortgage their lands for money to buy food, and the number of homeless people greatly increased, as did petty crime. An undernourished population was dealt a further blow in 1347 in the form of a virulent new disease, later called the Black Death (Map 14.3). The symptoms of this disease were first described in 1331 in southwestern China, then part of the Mongol Empire. From there it spread across Central Asia by way of Mongol armies and merchant caravans, arriving in the ports of the Black Sea by the 1340s. In October 1347 Genoese ships traveling from the Crimea in southern Russia brought the plague to Messina, from which it spread across Sicily and into Italy. From Italy it traveled in all directions.

Most historians and almost all microbiologists identify the disease that spread in the fourteenth century as the bubonic plague, caused by the bacillus Yersinia pestis. The disease normally afflicts rats. Fleas living on the infected rats drink their blood and pass the bacteria that cause the plague on to the next rat they bite. Usually the disease is limited to rats and other rodents, but at certain points in history the fleas have jumped from their rodent hosts to humans and other animals.

Black Death Stages and Symptoms

| Initial Stage | Appearance of boil, or bubo (growth the size of a nut or an apple in the armpit, the groin, or on the neck) |

| Secondary Stage | Appearance of black spots or blotches caused by bleeding under the skin |

| Final Stage | Victim begins to cough violently and spit blood; death follows in two or three days |

Most people believed that the Black Death was caused by poisons or by “corrupted air” that carried the disease from place to place. They sought to keep poisons from entering the body by smelling or ingesting strong-

Of a total English population of perhaps 4.2 million, probably 1.4 million died of the Black Death in its several visits. In Italy densely populated cities endured incredible losses. Florence lost between one-

In the short term the economic effects of the plague were severe because the death of many peasants disrupted food production. But in the long term the dramatic decline in population eased pressure on the land, and wages and per capita wealth rose for those who survived. The psychological consequences of the plague were profound. Some people sought release in wild living, while others turned to the severest forms of asceticism and frenzied religious fervor.