Understanding World Societies:

Printed Page 444

Papal Reforms and the Council of Trent

In 1542 Pope Paul III (pontificate 1534–

Pope Paul III also called a general council, which met intermittently from 1545 to 1563 at Trent, an imperial city close to Italy. The decrees of the Council of Trent laid a solid basis for the spiritual renewal of the Catholic Church. It gave equal validity to the Scriptures and to tradition as sources of religious truth and authority. It reaffirmed the seven sacraments and the traditional Catholic teaching on transubstantiation (the transformation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist). It tackled the disciplinary matters that had disillusioned the faithful. The council also required every diocese to establish a seminary for educating and training clergy. Finally, great emphasis was placed on preaching to and instructing the laity, especially the uneducated. For four centuries the doctrinal and disciplinary legislation of Trent served as the basis for Roman Catholic faith, organization, and practice.

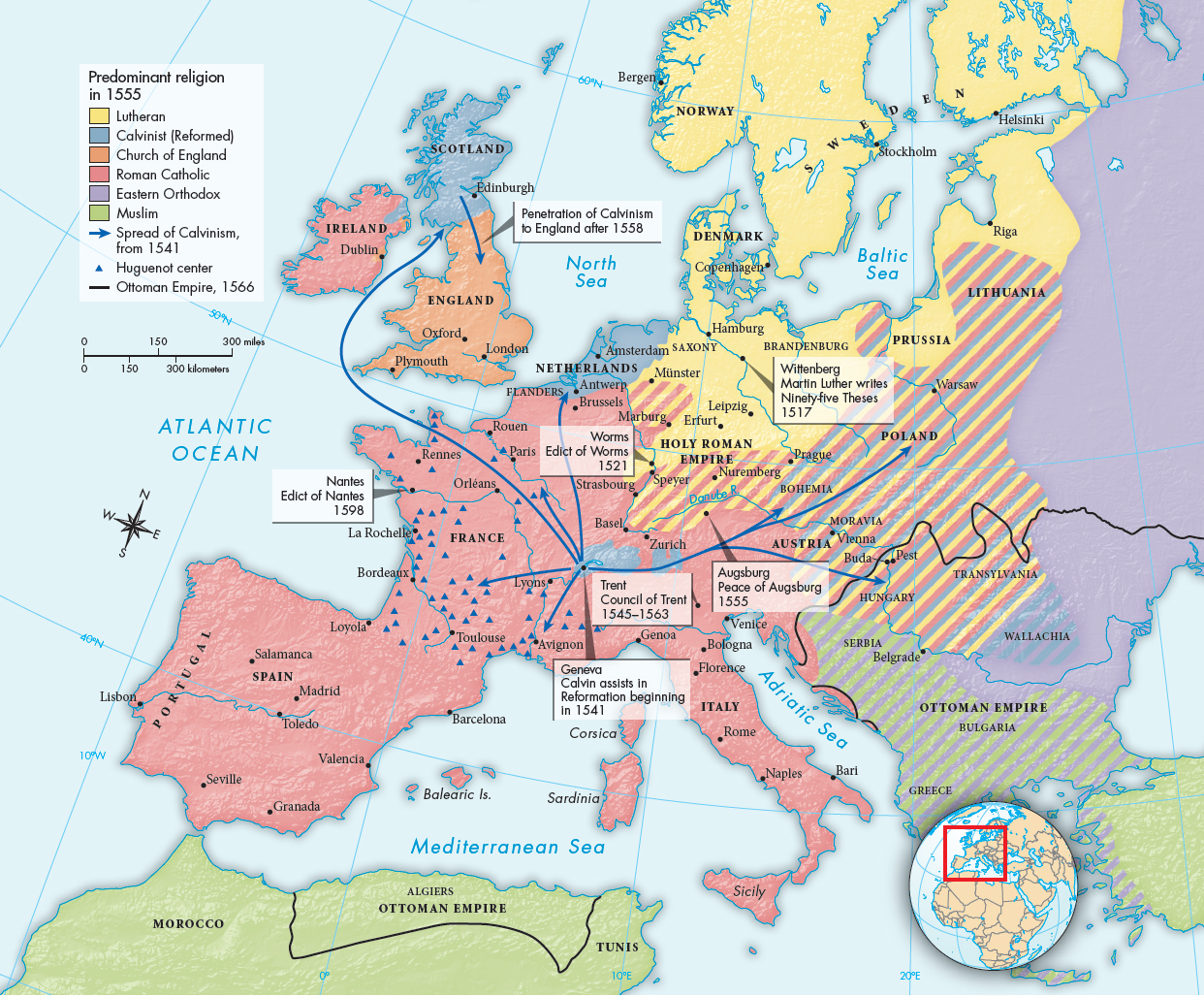

ANALYZING THE MAP: Which countries in Europe were the most religiously diverse? Which were the least diverse?CONNECTIONS:: Where was the first arena of religious conflict in Europe, and why did it develop there and not elsewhere? What nonreligious factors contributed to the religious divisions that developed in sixteenth-