Understanding World Societies:

Printed Page 634

Piracy and Japan’s Overseas Adventures

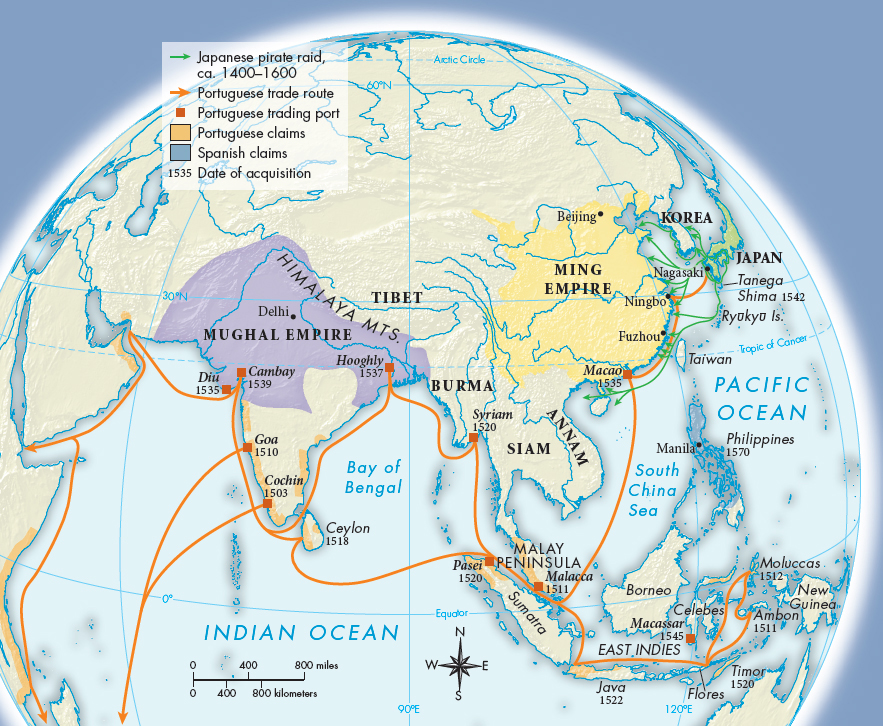

One goal of Zheng He’s expeditions was to suppress piracy, which had become a problem all along the China coast. Already in the thirteenth century social disorder and banditry in Japan had expanded into seaborne banditry, some of it within the Japanese islands around the Inland Sea (Map 21.3), but also in the straits between Korea and Japan. Although the pirates were called the “Japanese pirates” by both the Koreans and the Chinese, pirate gangs in fact recruited from all countries. The Ryūkyū (ryoo-

Possibly encouraged by the exploits of these bandits, Hideyoshi, after his victories in unifying Japan, decided to extend his territory across the seas. In 1590, after receiving congratulations from Korea on his victories, Hideyoshi sent a letter asking the Koreans to allow his armies to pass through their country, declaring that his real target was China. He also sent demands for submission to countries of Southeast Asia and to the Spanish governor of the Philippines.

In 1592 Hideyoshi mobilized 158,000 soldiers and 9,200 sailors for his invasion and equipped them with muskets and cannon, which had recently been introduced into Japan. His forces overwhelmed Korean defenders and reached Seoul within three weeks and Pyongyang in two months. A few months later, in the middle of winter, Chinese armies arrived to help defend Korea, and Japanese forces were pushed back from Pyongyang. A stalemate lasted till 1597, when Hideyoshi sent new troops. This time the Ming army and the Korean navy were more successful in resisting the Japanese. In 1598, after Hideyoshi’s death, the Japanese army withdrew, but Korea was left devastated.

After recovering from the setbacks of these invasions, Korea began to advance socially and economically. During the Chosŏn Dynasty (1392–