Understanding World Societies:

Printed Page 890

The Arab Revolt

Long subject to European pressure, the Ottoman Empire failed to reform and modernize in the late nineteenth century (see “Decline and Reform in the Ottoman Empire” in Chapter 25). Declining international stature and domestic tyranny led to revolutionary activity among idealistic exiles and young army officers who wanted to seize power and save the Ottoman state. These patriots, the so-

For centuries the largely Arab populations of Syria and Iraq had been tied to their Ottoman rulers by their common faith in Islam (though there were Christian Arabs as well). Yet beneath the surface, ethnic and linguistic tensions simmered between Turks and Arabs.

Young Turk actions after 1908 made the embryonic “Arab movement” a reality. The majority of Young Turks promoted a narrow Turkish nationalism. They further centralized the Ottoman Empire and extended the sway of Turkish language and culture. In 1909 the Turkish government brutally slaughtered thousands of Armenian Christians, a prelude to the wholesale massacre of more than a million Armenians during the First World War. Meanwhile, Arab discontent grew.

When in 1915 some Armenians welcomed Russian armies as liberators after years of persecution, the Ottoman government ordered a genocidal mass deportation of its Armenian citizens from their homeland in the empire’s eastern provinces. American ambassador to Constantinople Henry Morgenthau included this photo in his 1918 autobiography, Ambassador Morganthau’s Story, with this caption: “Scenes like this were common all over the Armenian provinces in the spring and summer months of 1915. Death in its several forms — massacres, starvation, exhaustion — destroyed the larger part of the refugees. The Turkish policy was that of extermination under the guise of deportation.” (© Bettmann/Corbis)

During World War I the Turks aligned themselves with Germany and Austria-

Arab bitterness was partly directed at secret wartime treaties between Britain and France to divide and rule the old Ottoman Empire. In the 1916 Sykes-

A related source of Arab frustration was Britain’s wartime commitment to a Jewish homeland in Palestine. The Balfour Declaration of November 1917, made by the British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour, offered British support for the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Some British Cabinet members believed the Balfour Declaration would appeal to German, Austrian, and American Jews and thus help the British war effort. Others sincerely supported the Zionist vision of a Jewish homeland (see “Arab-Jewish Tensions in Palestine”), but also believed that Jews living in this homeland would be grateful to Britain and thus help maintain British control of the Suez Canal.

In 1914 Jews made up about 11 percent of the predominantly Arab population in the Ottoman territory that became, under British control, Palestine. The “national home for the Jewish People” mentioned in the Balfour Declaration implied to the Arabs — and to the Zionist Jews as well — some kind of Jewish state that would be incompatible with majority rule.

After failed efforts at the Paris Peace Conference to secure Arab independence, Arab nationalists met in Damascus at the General Syrian Congress in 1919 and unsuccessfully called again for political independence. Ignoring Arab opposition, the British mandate in Palestine formally incorporated the Balfour Declaration and its commitment to a Jewish national home. In March 1920 the Syrian National Congress proclaimed Syria independent, with Faisal bin Hussein as king. A similar congress declared Iraq an independent kingdom.

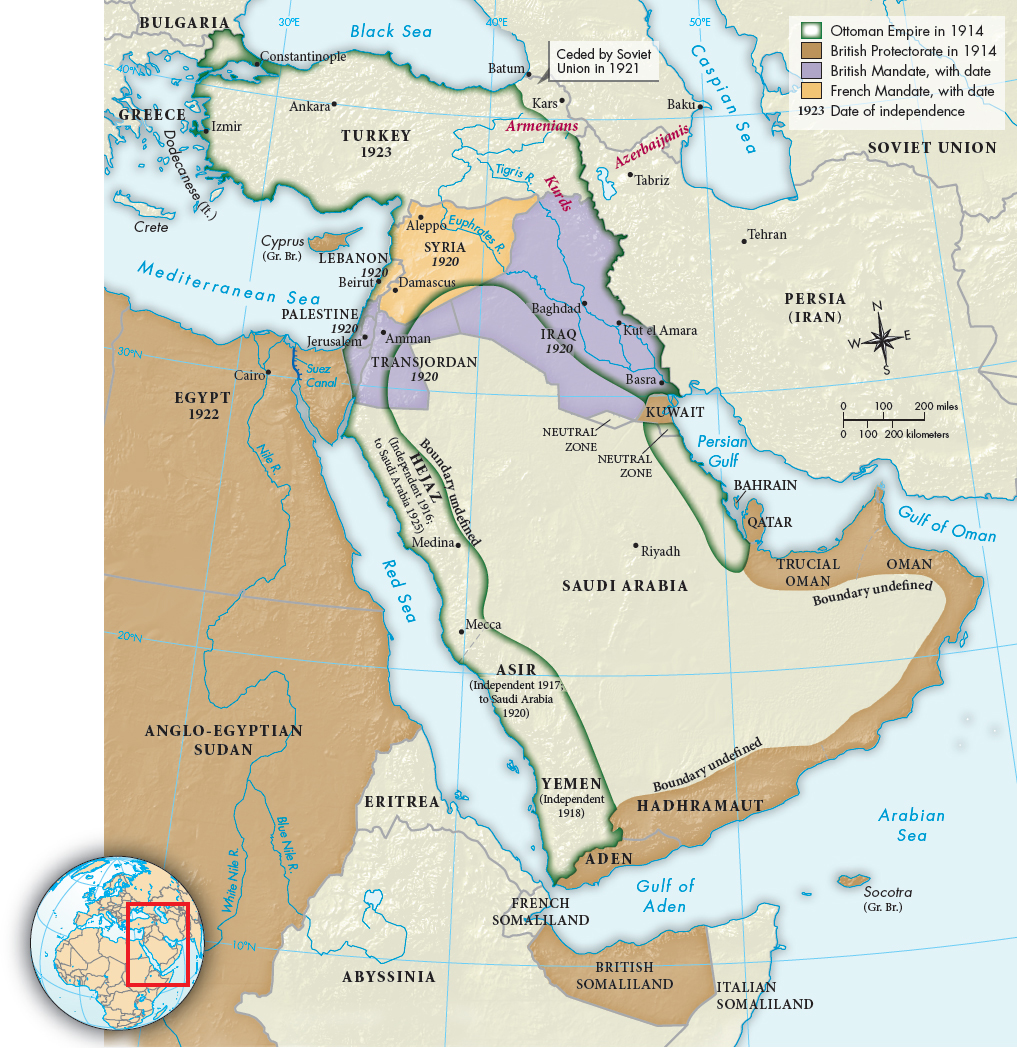

Western reaction to events in Syria and Iraq was swift and decisive. A French army stationed in Lebanon attacked Syria, taking Damascus in July 1920. Faisal fled, and the French took over. Meanwhile, the British put down an uprising in Iraq and established effective control there. Western imperialism appeared to have replaced Turkish rule in the Middle East (see Map 29.1).

ANALYZING THE MAP: What new countries were established as a result of the partition of the Ottoman Empire? Where were mandates established? What might you conclude about European views of the Middle East based on how Europe divided up the region?CONNECTIONS: How might the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in World War I have contributed to the current situation in the Middle East?